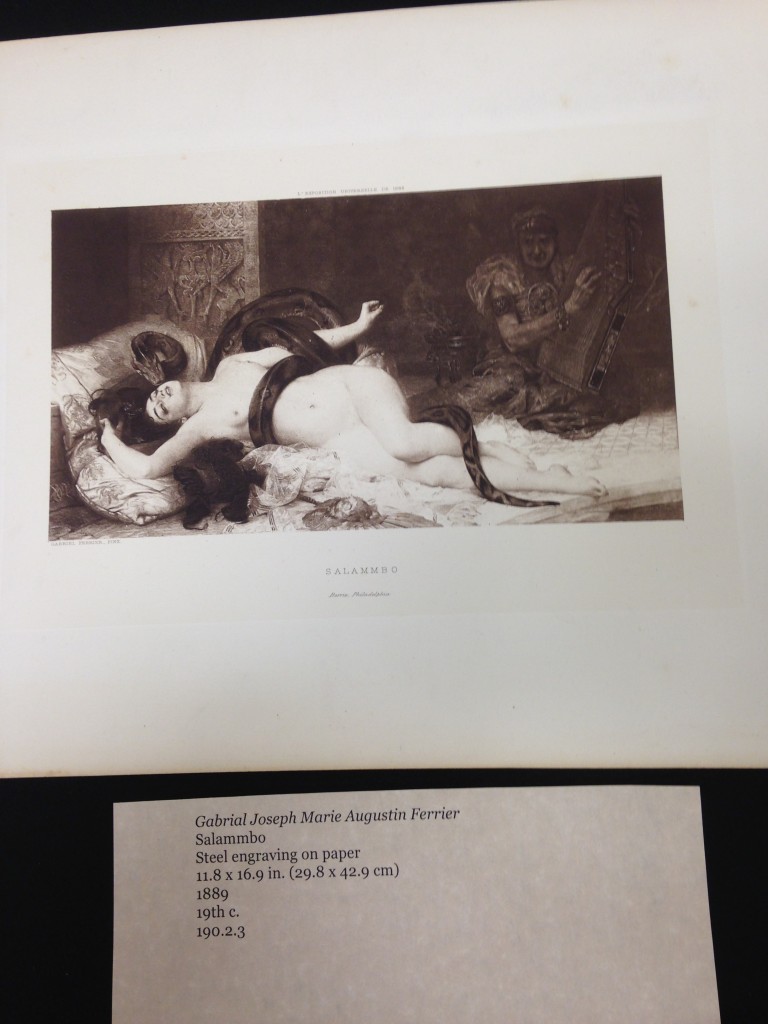

In his book, The History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault states in his introduction that “if sex is repressed, that is, condemned to prohibition, nonexistence, and silence, then the mere face that one is speaking about it has the appearance of deliberate transgression. A person who holds forth in such language places himself to a certain extent outside the reach of power; he upsets established law; he somehow anticipates the coming freedom” (Foucault 6). Foucault’s lens of sexuality could be corresponded with the untamable power men associated with the femme fatale, during the nineteenth century. The femme fatale can be examined as the person upholding sexual language that is “outside the reach of power; [she] upsets established law,” which the men around her dictate (6). Her ability to control the men around her with her sexuality causes a male panic that results in sexual repression over her female body. Her sexual freedom foreshadows a future of egalitarianism where the male is not the superior gender, but equal or inferior in sexuality. Salammbo, the woman engaged in sexual ecstasy in Salammbo by Gabrial Joseph Marie Augustin Ferrier, upsets the balance of sexual power beyond her identification with the femme fatale. In this drawing she controls every aspect of her sexuality through her gaze, her body language, her relationship with her snake, and most importantly through her status in society.

Salammbo is the political leader and representative of her tribe. Her ability to relate with a snake, an extremely, mysterious and solitary animal exoticizes her sexuality. The snake is a symbol of the tribe’s power, and her intimate relationship with it through sexual pleasure emphasizes her dominance over the tribe and the viewer. She is completely engaged in her own sexual enjoyment and posses her sexuality entirely. Salammbo exemplifies the ultimate femme fatale, a women who is truly independent and does not need male attention or support. The priest in the background exists in relation to her needs. He works for her, and she uses him for her political and sexual needs. Her position as a female leader, with immense sexual control expresses one of the the core pieces to Foucault’s argument. Salammbo exists unrestrained by law and sexual repression because she does not allow it bar her expression. She is entirely free and thus rises above “the regime of power-knowledge-pleasure that sustains the discourse on human sexuality” (11). Salammbo’s identity is exposed and vulnerable because it is truthful and guiltless. She is not harboring her identity by presenting a facade of power and strength. On the contrary, she empowers herself by embracing her sexuality and revealing her identity truthfully with confidence.