Upon viewing Jean-Paul Jamin’s engraving, “Tragedy of the Stone Age” many different themes come to mind. However, what I think is most interesting about the image is that it suggests a deeper meaning and relationship between man vs. nature, one that reflects the natural world as stronger than man. The lion in the image has clearly claimed the woman as his own and will not give her up for anyone or anything. The placement of the lions paws upon her hip and neck is a clear depiction of its dominance over the woman and is also highly sexualized. Upon discovering this scene the male within the engraving is exclaiming in horror and shock, as his face suggests in addition to his hands that are extended as he is dropping the instrument he was holding. The shock of the man when he sees his partner in jeopardy compared to the calmness and power of the lions face illuminates a moment when man cannot outsource the natural world. While the man had a successful hunt as the dead deer he is holding suggests, he ultimately cannot dominant all animals as he has been successfully doing. Additionally this animal-human paradox is translated within “Alice and Wonderland” many times as Alice discovers that she is often less knowing than the animals around here. Wonderland is a place that includes much more intelligent and powerful animals in compared to the world that Alice comes from. Despite Alice being new to Wonderland she at many times forces herself in spaces where she doesn’t exactly belong, for example the scene where she immediately sits at the table with the other animals, and is even questioned as to why she has sat down. However, through the context of the engraving one may ask themselves whether the lion has trespassed into man’s cave, or whether man trespassed within the lions den? With this in mind I am forced to question the relationships between Alice and the animals… Who is overstepping personal boundaries? Is anyone naturally given there own space? Can humans be considered animals? Why? Why not?

Category: 360: Victorian Sexualities

Expectations and the Other Reality

In Alice in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll brilliantly defies all expectations. The form alone is very different from the standard Victorian novel and its content is even more foreign. In fact, to Alice and her readers, everything is foreign in Wonderland. Language is contorted, reason and logic appear senseless, and no previously learned schemas or scripts can be applied to aid our understanding of Wonderland and its inner-workings. This is demonstrated repeatedly throughout the book.

For one, animals do not talk or wear clothing in reality. But in Wonderland’s reality, they do. When Alice first unfurls this nuance in meeting the Rabbit, “it all seem[s] quite natural” that the Rabbit runs around talking to itself, but when she thinks about it afterwards “it occur[s] to her that she ought to have wondered at this” (2). Here the lines of expectations and reality are blurred. Alice is a smart girl who has a strong sense of how the world works, but at this particular moment she allows a foreign reality (this Other reality in which animals audibly talk to themselves) to supersede any expectations or preconceived notions of the facts of her existence.

Once Alice is deeper into Wonderland, she defines her expectations and reality much more clearly. For example, when Alice enters the Duchess’s house she is appalled that the cook would throw pots and pans at the Duchess and her baby, but “the Duchess took no notice of them even when they hit her” (48). In Alice’s preconceived schema for what a home should look like, throwing pots and pans certainly does not jive. But the scene does not phase the Duchess— she does not flinch or consider herself a victim of domestic violence as Alice assumes. There is an obvious tension between Alice’s expectations of reality and the Other reality within the Duchess’s home.

I call Wonderland the Other reality because it exists in the book as a reality that exists alongside Alice’s perception of reality while also opposing it. The Other reality is an unexpected reality whose credibility Alice chooses to accept or deny.

We can explore another example of the Other reality in examining Jean-Paul Jamin’s engraving, “Tragedy of the Stone Age.”

Upon first glance, this painting seems not unordinary, much like how the Rabbit did not appear unordinary to Alice. After some time though, the Other reality reveals itself more clearly. The first thing I see when I look at this painting is that the lion has killed a woman– not a terribly common situation, but it is not surprising either– which would explain the man’s anguish and grief. But then I notice that the man is a hunter, too– a predator of does. Knowing this, the man’s expression shifts from one of grief to one of aggression. And now a parallel reality is unveiled; the Other reality here is the reality in which man and lion are peers of lust, power, and strength and the woman and the doe are their victims. But it is up to the viewers to consider their own expectations and realities, like Alice, in order to actively accept or deny this Other reality.

Is Alice Free in Wonderland?

“Still she went on growing, and, as a last resource, she put one arm out of the window, and one foot up the chimney, and said to herself ‘Now I can do no more, whatever happens. What will become of me?’

Luckily for Alice, the little magic bottle had now had its full effect, and she grew no larger: still it was very uncomfortable, and, as there seemed to be no sort of chance of her ever getting out of the room again, no wonder she felt unhappy.”

I chose a passage in the beginning of the book, where Alice is first experiencing her stages of uncontrollable growing and shrinking. Throughout Alice in Wonderland, I noticed that Alice’s lack of control over anything that happens to her was a common theme. Specifically, Alice is often trapped or confined to an area, which I read as a metaphor for the boundaries women faced in the Victorian era.

In this passage specifically, in the fourth chapter of Alice in Wonderland, I felt as though her physical growth and the negativity it brought mirrored what happened as people grew older. Specifically for female children, I believe they’re given more freedom as children than they are as adults. Children can say and do things that offend people, but are excused because of their age, and lack of understanding of the consequences. But, as they grow older, they are reprimanded, and unable to do things like play outside or explore the world independently, as Alice does in Wonderland. When Alice asks the question “What will become of me?” I think it’s interesting that there’s no evidence of her panic or hysteria in this moment. She is simply asking the question, and is not asking herself what she can do to get out of the situation, but is admitting she cannot help herself further, leaving the solution to someone or something else. The ending of the passage, “there seemed to be no sort of chance of her ever getting out of the room again, no wonder she felt unhappy.” I felt was a reflection of Alice’s fears of growing older and being confined to a set of responsibilities and chores. It was a happy coincidence that Alice grew just to the point of being too big for the room, and not bigger still. I think this section would have been interesting if Alice grew so big she broke the barriers of the room and was free to the outside world.

The physical entrapment of Alice in this passage strongly alluded to the invisible barriers women faced in the Victorian era. I felt as though Alice’s situation here reflected her fears, and the eventual end to her freedom in Wonderland.

Alice’s Adventures in Puberty

Alice’s journey in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland can be interpreted as a metaphor for her transition from child to adult. This would then suggest that Wonderland becomes a place for Alice to go through puberty, and the sister’s narrative at the end of the novel suggests that she has become an adult.

Alice’s realization that Wonderland is “nonsense” suggests that she has grown out of its wonders: ‘”No, No!” said the Queen. “Sentence first – verdict afterwards.” “Stuff and nonsense!” said Alice loudly. “The idea of having the sentence first!” (102). In comparison to many earlier events in the novel, when Alice for the most part seemed perplexed or fascinated by Wonderland’s creatures and events, Alice here takes a firm stance on her beliefs of what is right and wrong. This suggests that she no longer is susceptible to possibly accept the “nonsense” of Wonderland, and goes by real life’s “rules” that she sentence should follow the verdict.

Alice also feels superior to the cards at the end of the novel: ‘“Who cares for you?” said Alice (she had grown to her full size by this time). “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”’ (102). Her realization that they are “nothing but…cards” further suggests that she has lost Wonderland’s sense of fantasy as reality, and is “superior” to childhood’s ideas. Additionally, the note that she has grown to her full size after multiple changes to her body in the novel, and her waking up right after growing to her right size (102), further suggests that Wonderland is a place for childhood, which she no longer belongs to. The multiple changes to her body in the novel can symbolize her transition through puberty, as she does not understand all the changes that she experiences, and the end of those changes implies that she has now grown to become an adult.

The sister’s narrative about how Alice will one day tell her children of Wonderland further implies that Wonderland is only accessible to children: “…she pictured to herself how this same little sisters of hers would…be herself a grown woman… and…gather about her other little children, and make their eyes bright and eager with many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream of Wonderland long ago” (104). The sister’s idea of how Alice will one day gather her children is reminiscent of how Alice already told her sister her dream, which implies that she already is “a grown woman.” Alice’s leaving Wonderland, telling her sister her tale, and then running off thinking “what a wonderful dream it had been,” seems then to symbolize her leaving behind her childhood.

The Isolated Youth of the 19th Century

I have chosen to write about Illman & Sons’ The Greek Maiden. The engraving depicts a somewhat young-looking woman alone, staring off either into the distance or simply zoning out—it’s difficult to tell where her gaze is directed. Either way, she does not seem to be engaged in the current moment. The woman appears almost unaware of the artist. Her solitariness gives off a sense of isolation. Perhaps, because of this isolation and the somewhat melancholy look on her face, she feels as though she does not belong in the society in which she resides. This may be what she is thinking about—the cause of her miserable expression. The location she sits in may be the spot she escapes to to have some alone time.

This woman reminds me of Carroll’s character Alice. Alice, being rather strange, does not seem to fit in with what the youth of the Victorian era was expected to be. However, this may have been a common occurrence for 19th century children, for kids are often not naturally born prim and proper. I can imagine that nearly all youth felt isolated in the Victorian era, not yet respected as fully functioning members of society until their superiors felt they were mature enough. Alice and this Greek maiden, like many children, feel out of place in their environment. Alice does not fit into Wonderland either.

This Wonderland may have been a way for Alice to rid herself, even for just a few hours, of her strict and possibly unfulfilling life. Although Alice was unconscious during her escape, this may be what the Greek maiden is seemingly lost in—a daydream. Both pieces might speak about the pressures youth and women felt and still feel today, as well as the temptation to get away from it all.

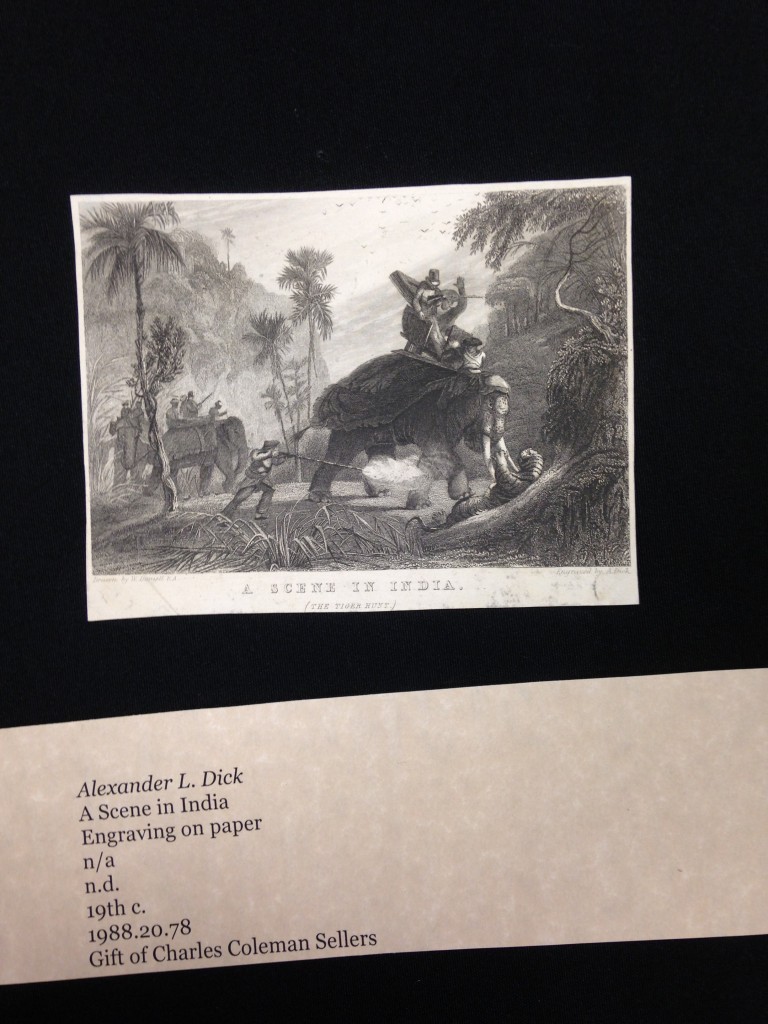

Some observations on the exoticism of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and A scene in India

Beside being a book for children, Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland can also be read as an implicit reference to exoticism. At the time the novel was published (1865), in fact, such a theme was particularly topical, due to the English empire’s expansionism towards far and unexplored places, such as Africa and India.

By adopting such a lens in reading the novel, the underground world that Alice encounters is a metaphor for the other, for the exotic, for the remote reality that scares the English conqueror and thus needs to be codified and explained through familiar means. In this particular case, it is the fantasy to fulfill such a duty. Alice becomes then the English soldier exploring a new world and its new creatures, and making her experience understandable to the rest of the world through literary means which make the unfamiliar (the exotic) familiar ( that is, available to everyone, even if it is far away). At the end of the novel, Alice wakes up and discovers it was all of a dream, but as soon as she runs off, her sister is ready to experience the same dream she just had. Two implications can be drawn from this conclusion. Firstly, that English colonialism is predestined to last as little time as the time of a dream, for a variety of reasons, incomprehension of the exotic individual and in-hospitality of the exotic place being the two main ones. As soon as one soldier (or population or country) walks away, however, there is another one ready to step in. Secondly, that the exotic individual does not want any foreign invasion. We can find examples of these points all throughout the novel, when Alice is continuously changing in shape to fit in specific places and situations in her underground journey, as to to say that her ‘normal’ shape is unsuitable to such a world. What is more, a clear allusion to the unwillingness of the local people to have a colonizer clearly comes from the scene at the tea party. Here, when the creatures see Alice coming, they immediately cry out:”No room!No room!”(53), and soon after March Hare tells her:”It wasn’t very civil of you to sit down without being invited”(53). This is a clear reference to the English invaders craving for new territories to take over and new people to colonize.

By adopting this particular point of view, Alice in Wonderland is an attempt to codify the unfamiliar and exotic through the eye of a child and through the familiar means of fantasy. In other cases, the exotic individual was seen as a threat to eliminate in order to take over his territories.  This is particularly true in Alexander L.Dick’s painting A scene in India, where the tiger stands for the exotic threat that the conquerors are trying to kill to have full control over its territory. This time the representation of the exotic individual is more realistic but at the same time unrealistic, since he is dis-humanized and compared to an animal. There is no willingness to understand and make the encounter with the exotic intelligible to others here, neither any sign of fear of such an encounter. There is just the desire of the conquest.

This is particularly true in Alexander L.Dick’s painting A scene in India, where the tiger stands for the exotic threat that the conquerors are trying to kill to have full control over its territory. This time the representation of the exotic individual is more realistic but at the same time unrealistic, since he is dis-humanized and compared to an animal. There is no willingness to understand and make the encounter with the exotic intelligible to others here, neither any sign of fear of such an encounter. There is just the desire of the conquest.

Animals and the Hierarchy of Wonderland

Throughout the pieces of Victorian art and literature that we have examined so far, animals frequently stand in for savagery or primitivism. Many of these pieces of art portray humans in competition with animals, exhibiting a clear distinction between the two categories. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland perpetuates this distinction, fitting animals and humans into a hierarchy that mimics the relationship between royalty and peasantry. Through Alice, we get an objective view of this world, and can examine how its inhabitants interact.

When Alice arrives in Wonderland, she notices that the world is divided into two distinct sections. There is the region before the tiny door, and the region beyond it. Immediately, we are introduced to the difference between these two areas: before the door is a “dark hall,” while beyond it lie “beds of bright flowers” and “cool fountains” (Carroll 8). Clearly, the space beyond the door is the more desirable area of this world, and is only accessible to a select few—those who can fit through the door. The door sets up the differences between the social classes of Wonderland, as well as the lack of opportunity to move between those classes. Accordingly, the image of Alice staring longingly out the door and into the beautiful gardens shows her desire to climb the social ladder.

The inhabitants of Wonderland further establish the structure of its social classes. In the “dark hall,” Alice encounters a wide variety of animals, including the White Rabbit, the Mouse, and a group of birds. On this side of the door, there are very few humans, and many of the animals are employed in the service of one particular human—the Duchess. The positioning of most of the animals on the less desirable side of the door, as well as the traditional view of animals as inferior to humans, suggest that in Wonderland, animals are part of a lower social class. This idea is supported by the fact that the rulers of Wonderland, who live in the “loveliest garden you ever saw,” are portrayed as humans. As a human, it is Alice’s birthright to be among this ruling class, and her acceptance of this role is illustrated in her poor treatment of the animals in Wonderland.

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and the Loss of Childhood Innocence

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is a story about growing up. While her sister states that Alice “would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood,” (104) if we look more closely at the conclusion of Alice’s time in wonderland, we can also see a loss of childhood innocence which brings the sister’s assertion into question.

Throughout the story, Alice tries to apply rational (if imperfect) understanding to completely irrational circumstances: as she falls down the rabbit hole, she muses about whether she’s reached the center of the earth (2-3) and applies similar lines of thought to her experiences throughout wonderland. Through it all, she never questions that the irrational things she sees are real. However, at the conclusion of the story, this begins to change and is signified by Alice’s growth at the trial.

Until this moment, when Alice changes size throughout the story, it is always due to the effect of some food or drink. Here, it is different: “in his confusion [the Mad Hatter] bit a large piece out of his teacup instead of the bread-and-butter. Just at this moment Alice felt a very curious sensation until she made out what it was: she was beginning to grow larger again” (92). What prompts her growth her is the Mad Hatter’s eating of his teacup, evidenced by Carroll’s use of “Just at this moment.” Something about this incident causes her to start growing, and it is her recognition of his action as improbable. Here, her realization is internal, and not fully formed.

Throughout the trial, she grows as she begins to point out the irrational: the narrator tells us “she had grown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn’t a bit afraid of interrupting [the king]” and tells him “‘I don’t believe there’s an atom of meaning in it'” (100). She now expresses her doubts aloud.

This culminates just before Alice wakes up from her dream, in the chapter tellingly titled “Alice’s Evidence.” Again, her realization of the improbability of wonderland corresponds with a description of her growth. As the Queen threatens to chop off her head one final time, we see Alice’s growth completed, and her childhood naiveté lost: “‘Who cares for you?’ said Alice (she had grown to her full size by this time). ‘You’re nothing but a pack of cards!'” Alice makes a clear, definitive statement about the nature of the cards. The cards swarm around her and she wakes up to find that it is nothing but leaves falling on her face (102).

Only when Alice recognizes the world around her as false–a delusion–is she freed from it. As soon as she declares that the court is “nothing but a pack of cards” she is transported out of the dream world and back into “dull reality” (104). Her voice is stronger each time, beginning with thinking and ending with shouting. Finally, the correlation of this awareness and physical growth lends itself to the idea that Alice is growing, mentally and physically. Her sister might believe she will retain her juvenile mindset, we all learn, once something magical is proven false, its wondrous quality is impossible to recover.

It’s All About Communication

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9dFDfOi_-ss

One ongoing complexity seen in Alice’s Adventure’s in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll, is that of miscommunication. There are several examples of this throughout the novel. For example, once in Wonderland, Alice has significant difficulty reciting lessons and poems she knows. She is unable to formulate thoughts and seldom understands what other characters are trying to convey to her.

In the chapter in which Alice is talking to the caterpillar, he asks her to recite the poem “You are old, Father William,” however, she is unable to do so. The caterpillar does not hesitate in notifying her she is wrong. Further, often times a word is stated, and interpreted in a way different than what was meant. This is depicted in the chapter “A Caucus Race and a Long Tale.” In this chapter, the mouse declares that it will tell a tale, as in a story. However, Alice incorrectly interprets this as the mouse talking about its tail. Thus, Alice pays close attention to the mouse’s appendage and fails to listen to the mouse’s story. The mouse then scolds Alice for her rudeness. Alice and the mouse had previous miscommunication when she brought up her cat, Dinah, which scared the inhabitants of Wonderland, yet she continued to talk about Dinah, unable to recognize why and how this was detrimental.

These points of miscommunication, along with many others within the novel cause the reader to wonder whether it is due to Alice’s ignorance or her being in Wonderland that is causing this language barrier to happen. It is intriguing that Alice accepts all of the illogical happenings in Wonderland, such as talking creatures, however, she fails to do something as simple as recalling lessons she has learned in school. Yet, throughout her journey, Alice tries to force her for of language on the creatures she encounters. This idea makes it seem as though Alice is the one at fault, and at the end of the day, she is desperately trying to alter the ways of Wonderland, rather than adapting to her new surroundings.

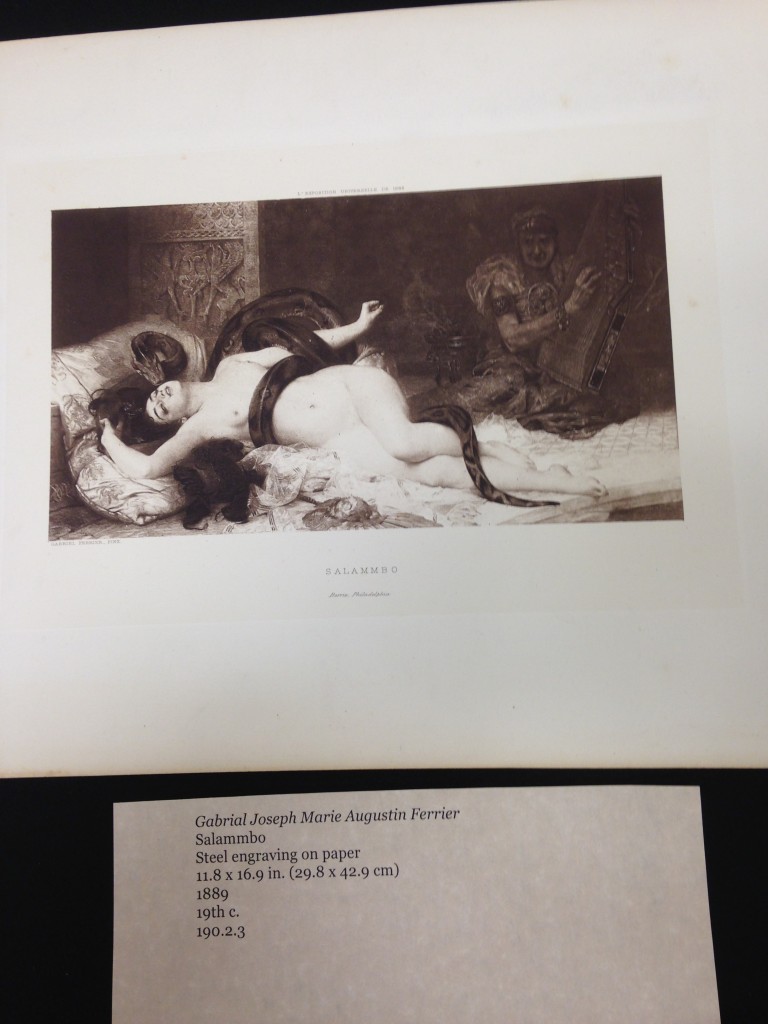

Sexual Freedom in Ferrier’s “Salammbo”

In his book, The History of Sexuality, Michel Foucault states in his introduction that “if sex is repressed, that is, condemned to prohibition, nonexistence, and silence, then the mere face that one is speaking about it has the appearance of deliberate transgression. A person who holds forth in such language places himself to a certain extent outside the reach of power; he upsets established law; he somehow anticipates the coming freedom” (Foucault 6). Foucault’s lens of sexuality could be corresponded with the untamable power men associated with the femme fatale, during the nineteenth century. The femme fatale can be examined as the person upholding sexual language that is “outside the reach of power; [she] upsets established law,” which the men around her dictate (6). Her ability to control the men around her with her sexuality causes a male panic that results in sexual repression over her female body. Her sexual freedom foreshadows a future of egalitarianism where the male is not the superior gender, but equal or inferior in sexuality. Salammbo, the woman engaged in sexual ecstasy in Salammbo by Gabrial Joseph Marie Augustin Ferrier, upsets the balance of sexual power beyond her identification with the femme fatale. In this drawing she controls every aspect of her sexuality through her gaze, her body language, her relationship with her snake, and most importantly through her status in society.

Salammbo is the political leader and representative of her tribe. Her ability to relate with a snake, an extremely, mysterious and solitary animal exoticizes her sexuality. The snake is a symbol of the tribe’s power, and her intimate relationship with it through sexual pleasure emphasizes her dominance over the tribe and the viewer. She is completely engaged in her own sexual enjoyment and posses her sexuality entirely. Salammbo exemplifies the ultimate femme fatale, a women who is truly independent and does not need male attention or support. The priest in the background exists in relation to her needs. He works for her, and she uses him for her political and sexual needs. Her position as a female leader, with immense sexual control expresses one of the the core pieces to Foucault’s argument. Salammbo exists unrestrained by law and sexual repression because she does not allow it bar her expression. She is entirely free and thus rises above “the regime of power-knowledge-pleasure that sustains the discourse on human sexuality” (11). Salammbo’s identity is exposed and vulnerable because it is truthful and guiltless. She is not harboring her identity by presenting a facade of power and strength. On the contrary, she empowers herself by embracing her sexuality and revealing her identity truthfully with confidence.