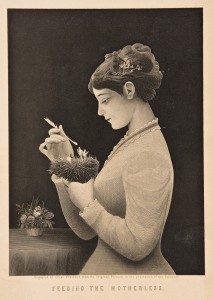

This image from the Trout Gallery called “Feeding the Motherless”, appears simple at first. At a glance, it looks plainly as if a well put-together woman is feeding motherless birds with the tip of a feather in a dark walled-room that also contains a table. Simple enough, right?

This image from the Trout Gallery called “Feeding the Motherless”, appears simple at first. At a glance, it looks plainly as if a well put-together woman is feeding motherless birds with the tip of a feather in a dark walled-room that also contains a table. Simple enough, right?

However, a closer reading would prove that this etching is filled with Victorian connotations, ideals and limitations. Primarily, one must address the woman’s attire. She is wearing a white dress displaying her purity and innocence, a characteristic of women in this period that our class can seemingly never escape. Her hair is pinned back with lovely white flowers and she is wearing limited make up. Right from the beginning one can assume that she is of a higher class based on her outfit. She need not go into other methods of making money (prostitution), and can instead spend her time looking around for motherless bird’s nests. The white flowers in her hair also suggest that although she is chaste and pure, she’s most likely blooming and ready to be married off.

Now, one must address this feeding action that is taking place. There are two seemingly competing ideas about what could be going on here. My initial reaction, was, hey this looks a lot Marian, and also she’s taking care of some smaller frailer creature resembling Laura. The woman appears to be very intent on the birds showing this sort of stark determination. Many other women in the other etching we saw in class display women looking off into the distance forlornly, or moaning for their lover. Rarely we see a woman physically doing something in an etching, in contrast to her normal role as the object itself. However, this image could also read the opposite. In the reading we read for class this Wednesday, the British Library discusses women’s role in the domestic sphere. The site says, “Not only was it their job to counterbalance the moral taint of the public sphere in which their husbands laboured all day, they were also preparing the next generation to carry on this way of life,” (British Library). In essence it was the woman’s role to nurture youth, and have them grow up in the ways in which society was governed. Thus this woman feeds these baby birds, and nurtures them showing her ability to thus assume this motherly role to a real human child. Her hair is blooming like her body, and she’s ready to get prego. The dark background of the photo adds to this well by promoting this woman as the object of motherhood. There’s no distractions, just this pure and fertile woman.

So this leaves me with questions. What does this say about Marian now? Although she acts through determination and vigor, can she still not escape these stereotypical gender roles? She in essence becomes the mother of Laura, and even plays a similar role to Laura’s newborn son, so does she achieve the same status of man? We had such high hopes for Marian, but it seems that the cards lie where they are. This image of this woman suggests, “Women were assumed to desire marriage because it allowed them to become mothers rather than to pursue sexual or emotional satisfaction,” (British Library). This woman depicting a motherly vibe, is more likely a more chaste way of telling the general public that she’s ready to nuptially open her legs.