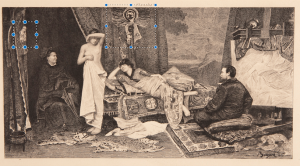

In Christina Rossetti’s poem, In an Artist’s Studio, we are guided around the studio of a painter who has depicted the same model as different characters. She becomes the queen, the virgin in a green dress, a saint, and an angel, but remains nameless throughout. The problem here is not just that the nameless girl remains nameless, but also that her body is used and objectified by this artist. She is no longer a person, but an aesthetic subject that is to be manipulated into a trope. Like Jen Marsh is quoted in Lee’s article “The Femme Fatale as Object”:

women are rendered decorative, depersonalized; they become passive figures rather than characters in a story or drama… women are reduced to an aesthetic arrangement of sexual parts, for male fantasies. (Marsh, The Pre-Raphaelite Sisterhood)

Sure, the model is lovely, but that’s all she is. She is a passive figure to be manipulated in the way the artist wishes she could be. The depersonalization of women figures into tropes is too common, and in terms of Victorian literature, it is inherently connected to sexuality. The well-known trope of the Femme Fatale is played out in another poem: My Last Duchess.

In Browning’s My Last Duchess, the Duke is narrating a story about his last Duchess, who is depicted in a painting that he keeps behind a curtain. In the Duke’s eyes, she fulfills the trope of Femme Fatale because she finds pleasure in being looked upon and speaking with men other than him. He sees that she smiles at everyone, and does not value him over everyone else. The Fatale part comes into play when he seemingly murders her to keep her from smiling at everyone, and now keeps her behind the curtain. In this instance, her sexuality is totally under the control of the Duke for the rest of eternity: only he can look upon the “spot of joy” on her cheeks.

Like Marsh and Lee assert in the essay, the Duchess is literally reduced to aesthetic parts – the painting to look upon and then move on from to other paintings. She no longer has agency – she is trapped in a painting, posed beautifully forever. The Femme Fatale is fascinating only because of what she used to be, the amalgam of fear over “female malevolence” and therefore, a control over her own sexuality. Now, as an object, she can be controlled and fascinate her onlookers on command.