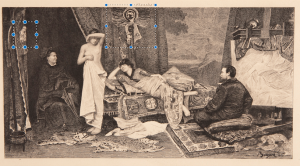

(Image: Yes or No? Illman Brothers, 19th century. n/a, n.d)

The above engraving depicts a woman in relatively typical Victorian fashion, laboring over some correspondence with an unknown conversational partner. The woman is surrounded by scraps of paper, most likely torn up by her as she tries to answer the question posed by the title of the piece: Yes or No?

Given the typical subject matter of the time period, it is likely she is corresponding with a suitor or lover–a man of some description. Before the woman is a box, filled with both paper and strings of beads. This seems to be some sort of storage container for precious objects. Clearly, the letters she is agonizing over mean a lot to her, enough that she would store them with her jewelry (the most prized possession of many women of both that time period and today). The presence of a four-poster bed in the background of the image, as well as a modesty screen suggests that the lady is writing in her own bedroom, the ultimate area of privacy. This suggests that this correspondence is either something she would prefer to hide, or something she feels is important enough to want absolute privacy as she makes up her mind as to the answer to the question.

The most interesting thing in this image, however, is the woman’s facial expression. She does not seem happy at all, and simply “pensive” does not seem to properly encompass the emotion displayed. The lady’s large eyes and quill pen at her lips seem to suggest a sort of sadness or regret, on top of just the simple thoughtfulness that is also portrayed.

The atmosphere of this print overall reminds me of the article on Victorian gender roles on the British Library website by Kathryn Hughes, in which she discusses the separate spheres that men and women were expected to inhabit during this time period. In the image, the woman is hidden away in her bedroom, shown to be solidly within the domestic sphere reserved for Victorian women. Hughes also mentions that “a young girl was not expected to focus too obviously on finding a husband.,” which may relate to the engraving if, indeed, the subject happens to be composing a letter to a male acquaintance or suitor. We have previously discussed in class how much Victorian language was encoded so as not to talk overtly about sex and sexuality–it is possible that the woman in the engraving is attempting to draft a reply to her lover that does not sound too forward, but also conveys her meaning well enough to be understood.

The imposition of societal gender norms on women in Victorian times may also account for the woman’s less-than-thrilled facial expression. As women were not supposed to necessarily enjoy the prospect of marriage or sexuality (being assumed to be more or less asexual as a whole [see William Acton’s medical text]) (Hughes), it would be understandable if the woman in the engraving was not portrayed as being eager to respond to a query from a lover–such correspondence would, naturally, be just an opportunity to gain the chance to produce children and fulfill the maternal duty. Though art oftentimes has messages undermining the social order of the time, the context given by Dr Flaherty seems to indicate that these engravings were indicative of the Victorian attitudes that American audiences desired to emulate, and would therefore likely not have contained such subversive messages.