Editors : Isabel, Julianna and Sophia

On the day Isabel arrived in Toulouse, her host family’s daughter eagerly asked if Isabel had ever heard the word “lull”. After some confusion, Isabel realized that this was not a French word, but rather the English text-shortcut ‘LOL’ pronounced in a French accent. This experience proved to be the first of many encounters with anglicisms in the langue française courante. A homeowner uses “scotch” to tape a “poster” on the wall, a parent “fait du shopping” every “week-end”, and a lycéen finds everything “cool” and even “likes” certain “Facebook” posts. So far one of the most surprising realizations from Toulouse is that French conversations contain quite a bit of English!

Globalization and the rise of linguistic borrowing

The use of anglicisms is so prevalent in French that it made us wonder, why are there so many English words? The use of foreign words is not particularly shocking on its own; after all, lexicons are flexible and the rise of intercultural contact in this era of globalization has left almost no language untouched. We have noticed plenty of examples of other non-English foreign words in French too, such as tsunami (Japanese), hijab (Arabic) and yoga (Hindi). Yet many of these terms differ from the English words in that they’re rather l imited – they tend to refer to specific events or practices from the culture of origin. The words borrowed from the English language describe more universal phenomena (le business, le babysitting) and are more frequently turned directly into French verbs (customiser, uploader), both of which indicate that English has more influence on French than other foreign languages. Given that the majority of these anglicisms come from sports, fashion, entertainment and online/social media vocabulary, it appears that the dominant English-speaking internet and entertainment culture is responsible for these additions to the French language.

imited – they tend to refer to specific events or practices from the culture of origin. The words borrowed from the English language describe more universal phenomena (le business, le babysitting) and are more frequently turned directly into French verbs (customiser, uploader), both of which indicate that English has more influence on French than other foreign languages. Given that the majority of these anglicisms come from sports, fashion, entertainment and online/social media vocabulary, it appears that the dominant English-speaking internet and entertainment culture is responsible for these additions to the French language.

Dire, ne pas dire

The prevalence of anglicisms in daily language has caught the attention of the French, too. In France, language is more than a means of communication; it is a matter of national heritage and culture. L’Académie française, a council of 40 writers and artists devoted to the protection of the French language and its integrity, takes a hardline stance against the use of anglicisms. This can be seen in the Académie’s website, which includes a section of anglicisms to be avoided in favor of their authentic French equivalents. The site warns against use of the words “networking”, “hotline” and “brainstorming”, suggesting instead “travail en réseau”, “numéro d’urgence”, et “remue-méninges” as proper French alternatives. The desire to safeguard the French language from English influence is also evident in the backlash to a 2013 proposition allowing French universities to teach a small number of courses in English. Although the bill passed, its critics called it a betrayal of national heritage and L’Académie Française went so far as to deem the proposal “linguistic treason.”

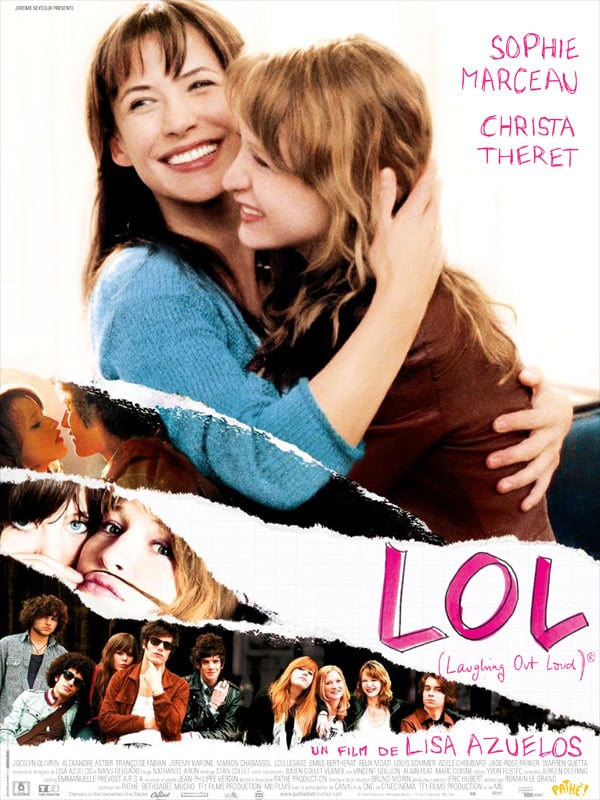

While certain sections of French society may regard the use of English words as a threat to national culture, the very need of L’Académie Française to dissuade French speakers from adopting anglicisms illustrates that not all French speakers share this attitude. Here lies a national quandary: though the French are fiercely proud of their language and seek to protect its evolution from foreign influence, many speakers are also eager to adopt English terms, phrases, and culture into their speech and way of life. For example, Isabel’s host sister has asked for American music recommendations that she can share with her friends. Additionally, nearly half of the movies shown at the local theaters in the last month have been American productions, some of which are shown with the original English soundtrack and French subtitles. Furthermore, many Dickinson students have been approached for babysitting jobs by parents seeking an English-speaking caretaker to improve their child’s acquisition of the language. These examples clearly demonstrate that English is popular and its status will not soon subside.

Should the French be worried about the increased use of anglicisms?

From an American point of view, the French perception of this issue a bit difficult to understand. News articles with dramatic titles such as “La langue française en danger?” (Le Monde), “Il y a une soumission française à l’anglais” (Le Figaro) and “Faut-il bannir les anglicismes?” (Europe1) reflect fears that do not exist to the same degree in the United States, a country with no official national language. Perhaps these seemingly alarmist French perspectives can be linked to the language’s apparent decline within the international sphere. For example, the percentage of French articles used in the European Commission decreased by 29 percentage points between 1997 and 2009; in contrast, English articles made up 72% of European Commission documents in 2006. Instances like these seem to beg the question as to whether the French language is losing prominence in favor of English and what should be done about it.

Ultimately, is this blending of languages and cultures a positive result of globalization and exchange, or a harmful threat to French identity and culture? Clearly, there are a multiplicity of different responses to this question among French citizens, and to give a single, sweeping answer fails to acknowledge the diversity of opinions among the French regarding their own language. In our increasingly globalized world, and throughout the remainder of our time as students here in Toulouse, it will be interesting to see in what ways the French reconcile these seemingly opposing interests: the desire to maintain linguistic heritage and tradition on one side, and the desire to participate in a system of global interchange increasingly dominated by the English language.

Leave a Reply