https://www.wevideo.com/embed/#2492269573

by Huy Trinh

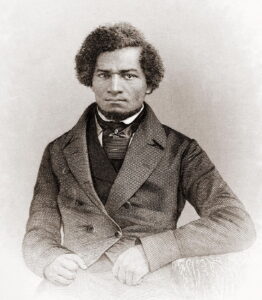

African American troops at Lincoln’s second inauguration (Wikipedia)

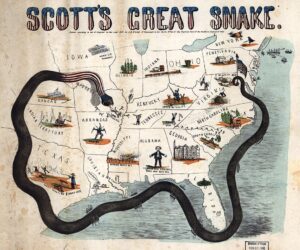

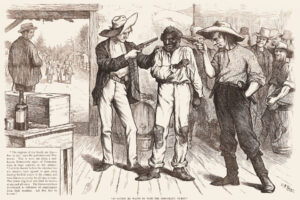

On March 4, 1865, a crowd the size of thirty-five to forty thousand people assembled in front of the East Portico of the Capitol, anxiously waiting for the beginning of Abraham Lincoln’s second term as the President of the United States. [1] The downpour earlier that morning did not stop the mass gathering in the capital, where for the first time ever a large number of “colored people” congregated at a presidential inauguration, noted a correspondent for the Times of London. [2] The correspondent was referring to the presence of African Americans, most of whom were likely former slaves, at the ceremony. They, among others in the crowd, came to the inauguration with high hopes for the future. The war was technically not over, but the Union was poised for victory as Ulysses S. Grant’s army tightened its grip on the Confederate capital of Richmond [3]. Many expected a grandeur declaration of victory from the president, who had proven himself an extraordinary leader in a turbulent chapter of the nation’s history. Others might have wanted to hear him demonizing the insurgents for perpetuating slavery and triggering the conflict in the first place. By the time the president finished his speech, however, those who came with such expectations must have been sorely disappointed.

Lincoln’s second inaugural address contains only over 700 words, making it one of the shortest inaugural speeches. [4] Yet it is considered by many historians, and even by Lincoln himself in his letter to Thurlow Weed, as his finest work. [5] One could not help but wonder how a seven-minute speech achieved such acclaim, especially when placed next to the more well-known Gettysburg Address, the lengthier First Inaugural Address, or the prophetic House Divided Speech?

For starters, the second inaugural address affirms slavery as the central issue over which the Civil War was fought:

One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. [6]

The affirmation reflects a major shift in Lincoln’s view of the conflict throughout his presidency. Standing on the same stage four years earlier, the new president emphasized his duty to preserve the Union, at a time when seven Southern states had already unilaterally parted ways with the federal government. He made a plea for peace and unity by assuring the South that he had no intention nor capacity whatsoever to interfere with the existing slavery institutions of those states. [7] To Lincoln, a more practical and achievable goal was likely to prevent the expansion of slavery into new territories in the West, which explained his decision to return to politics after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854.

As the war progressed, the roar for emancipation grew louder from radical abolitionists, and yet it appeared that Lincoln’s attention was affixed to saving the Union. When Horace Greeley lamented the president’s apparent lack of commitment to the emancipation of enslaved blacks, Lincoln offered a swift and assertive response in which he called saving the Union his “paramount object”:

My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. [8]

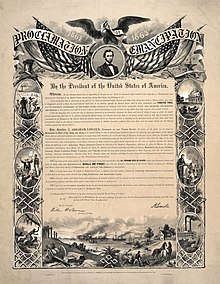

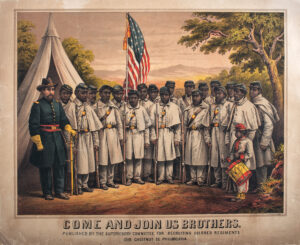

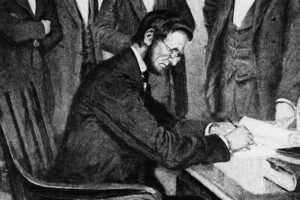

It is important to acknowledge that at the time of Lincoln’s exchange with Greeley, the president had already drafted the Emancipation Proclamation and was advised by William Seward to wait for a Union victory for a public announcement. At this point, however, Lincoln still contemplated the issues of race, slavery, and emancipation within the political and social context of the war, and not for the moral implications of the institution. A year earlier, he rescinded a proclamation issued by John C. Frémont – which freed the slaves in Missouri – out of fear that it would upset the neutrality of the border states. [9] When Lincoln officially issued his own proclamation on September 22, 1862, one might have viewed it as a political maneuver aimed to cripple the slave-dependent economy of the South while augmenting the strength of the Union forces by recruiting black soldiers. [10] Here, it seems that Lincoln saw emancipation as a means to achieve the ultimate purpose of preserving the Union, but not as the end of the war itself.

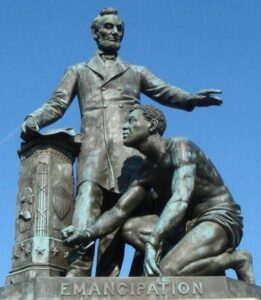

But there were also signs indicating that the Union commander-in-chief had wrestled with slavery as the core issue of the bloody war. Just a week before publishing his reply to Greeley, on August 14, 1862, he met with a group of prominent black men in the White House and suggested that free blacks should leave for another country, hinting that the president believed the departure of blacks from America would cause the fight to cease to exist. [11] And in his second inauguration, Lincoln finally defined the conflict as a war to abolish slavery, ensuring that the triumph of the Union means the collapse of this deplorable institution in the United States. To African Americans, this affirmation is a promise of racial equality and justice that they were denied for two hundred and fifty years on this continent – a promise made by the president and would be fulfilled by the president himself in his second term.

The second significance of the address lies in the inclusive tone of the words. Historian Ronald C. White notes that Lincoln was the first president that wins a second term since Andrew Jackson. Generally, a reelected president tends to open their inaugural remark with a statement of personal appreciation for the citizens who had entrusted the responsibility of leading the nation to them., the way Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and Andrew Jackson did. [12] By contrast, Lincoln in his 1865 address only used personal pronouns twice throughout the whole address. Instead, he employed extensively what White called “inclusive language”, with words like “both” and “all” appearing repeatedly [13]. Contrary to the hope of many spectators, Lincoln neither vented his anger toward the South nor professed any self-congratulations. The president again continued his inclusive language in the fourth paragraph:

Both read the same Bible, and pray to the same God; and each invokes His aid against the other. It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces; but let us judge not that we be not judged. The prayers of both could not be answered; that of neither has been answered fully. [14]

Lincoln reminded his aroused audience of the common ties between the North and the South, that the soldiers and the people of each side “read the same Bible” and “pray to the same God”. While Lincoln pointed out the irony in the way Southern people appealed to God as they simultaneously oppressed blacks, he immediately asserted in the following sentence: “…but let us judge not that we be not judged.” Here, the president cautioned his listeners against human’s tendency to judge and retribute, and instead encouraged a sense of understanding, empathy, and forgiveness from fellow Northerners [15]. He urged for his people, to recognize “American slavery” as an offence of a whole nation rather than letting the South bear the sole burden of wrongdoings, proclaiming that it was the will of God for the catastrophic war to break out, for it will cleanse the nation of the evils of slavery no matter how long it shall take.

In 700 words, there were no self-appraisals, no celebrating the military successes of the North, nor was there any chastisement of the South for tolerating and perpetuating the brutal subjugation of millions of blacks. Now a hardened politician after four tumultuous years in the capital, Lincoln understood that for “a new birth of freedom” to materialize, all hostilities must abate once the dust settles. The war was fought to resolve the hostilities and release the bitterness between two sides, and thus if hostilities and bitterness still persist after armed conflicts cease, “the war would have been in vain”. [16] Toward the end, all Lincoln tried to do was to extend an olive branch, offering the enemy his willingness to forgive and to enter a new era as a united nation of a united people:

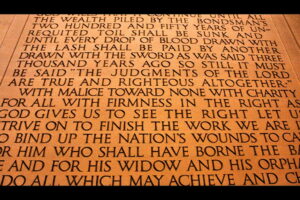

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations. [17]

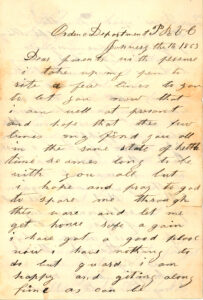

Lincoln meant every word he had said on that day. Months before he took the podium on March 4, 1865, the president had expressed his inclination for a conciliatory reconstruction. Two days after winning the election, he told a group of serenaders at the White House that he “[has] not willingly planted a thorn in any man’s bosom”, indicating his wish for a smooth and amicable restoration of the Confederate states into the Union. [18] Exactly a month after his speech, Lincoln visited the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, where thousands of frightened citizens inhabited after Robert E. Lee’s army fled the city. When asked by General Weitzel for advice on dealing with the locals, the president simply said, “I’d let ‘em up easy.” [19]

April 9, 1865, Lee and his army surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. With permission from Lincoln, the Commanding General of the Army extended his former foes a generous peace, allowing Lee’s soldiers to return home [20]. In addition, Grant provided rations for the ravaged Confederate army, and he ordered for all celebrations to come to a full stop, declaring that they were now countrymen again. [21] Grant’s acts were reflective of the president’s desire for reconciliation, and the defeated Lee felt nothing but gratitude for the goodwill he was offered.

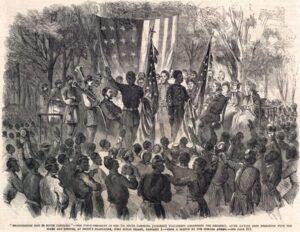

Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. (Wikipedia)

Now inscribed on the wall of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., the inauguration address of 1865 now holds a special place in American history. For renowned Lincoln scholar Ronald C. White, Lincoln’s words from more than 150 years still resonate today, and even more so in a polarized political climate. [22] The speech exemplifies the best of Abraham Lincoln – compassionate, insightful, and humble – just as how Abraham Lincoln “represents the best values of what it means to be an American” – to have the ability to understand and respect others’ opinions and engage in civilized, meaningful conversations. It is important then, for future American generations, to study Lincoln and understand the legacy he left behind, for there is no men of more consequence than he was.

[1] Ronald C. White, Jr., The Eloquent President: A Portrait of Lincoln Through His Words (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2006), 326.

[2] Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln: A Bibliography (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2009), 801.

[3] Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln: A Bibliography (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2009), 799.

[4] Jack E. Levin, Malice Toward None: Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address (New York: Threshold Editions, 2014), 11.

[5] Ronald C. White, Jr., The Eloquent President: A Portrait of Lincoln Through His Words (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2006), 352.

[6] “Second Inaugural (1865)”, Knowledge for Freedom Seminar, Accessed December 13, 2021. https://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/teagle/texts/second-inaugural-1865/

[7] Louis P. Masur, The Civil War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 23.

[8] “Letter to Horace Greeley (August 22, 1862)”, Lincoln’s Writings: The Multimedia Edition, Accessed December 13, 2021. https://blogs.dickinson.edu/hist-288pinsker/2015/04/28/lincolns-proclamation-of-thanksgiving-october-3-1863/

[9] Masur, 28.

[10] Masur, 56.

[11] Nikole Hannah-Jones, “The Idea of America” from The 1619 Project (New York, NY: The New York Times Magazine, 2019). [WEB]

[12] Ronald C. White, Jr., The Eloquent President: A Portrait of Lincoln Through His Words (New York: Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2006), 333-335.

[13] Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural Address. Films On Demand. 2015. Accessed December 12, 2021. https://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=104013&xtid=168685.

[14] “Second Inaugural (1865)”, Knowledge for Freedom Seminar, Accessed December 13, 2021. https://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/teagle/texts/second-inaugural-1865/

[15] Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural Address. Films On Demand. 2015. Accessed December 12, 2021. https://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=104013&xtid=168685.

[16] Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln: A Bibliography (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2009), 808.

[17] “Second Inaugural (1865)”, Knowledge for Freedom Seminar, Accessed December 13, 2021. https://housedivided.dickinson.edu/sites/teagle/texts/second-inaugural-1865/

[18] Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln: A Bibliography (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2009), 787.

[19] Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln: A Bibliography (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2009), 812.

[20] Ronald C. White, Jr., A. Lincoln: A Bibliography (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2009), 813.

[21] Masur, 79.

[22] Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural Address. Films On Demand. 2015. Accessed December 12, 2021. https://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=104013&xtid=168685.