From November through December 1864, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman led his army through Confederate-controlled Georgia on what became known as his “March to the Sea.” Over the course of their two-month, 235-mile trek, Sherman, his officers, and their men, destroyed or burned numerous buildings deemed essential to the Confederacy. Sherman believed his march was not one of rash or hostile greed or hatred; rather, he saw it as a response to the changing nature of war. To him the Union was, “not only fighting hostile armies, but a hostile people, and [we] must make old and young, rich and poor, feel the hard hand of war.” [1]Sherman’s “March to the Sea” shows Union strategy and prowess at the end of the war – aiming for and achieving the decimation of Confederate territory in order to convince Southern citizens to stop backing the war effort.

An occupation and march such as this was almost impossible without the leadership of men such as Sherman. His armies were aided by his confidence, strength, and organization for much of the early part of their campaign. The wings of infantry under his command moved, as planned, along roads and pathways determined before the march even began and did so with little to no disturbance by enemy forces. The disorganized enemy’s inability to execute an effective defense allowed Sherman and his men to march to Savannah with minimal casualties. With little Confederate resistance, the army was also able to deliver the harsh reality of war to the Georgian towns and institutions that it came across.

But the tactics and the strategy of Sherman’s March require thoughtful consideration. Noah Andre Trudeau, in his in-depth study Southern Storm (2008), notes how careful planning and military ingenuity of the march was unparalleled. The fact that Sherman was able to march so many men over an unfamiliar terrain, sometimes without the benefit of well-defined roads; negotiate fifteen river crossings, each more than 230 feet wide[2]; transport the necessary food and supplies for 62,000 troops with just 2,000 wagons (half the number the similarly sized Army of the Potomac used in its assault on Virginia in 1862); and still manage to emerge unscathed from the rubble in the Confederate stronghold of Savannah, was astounding. Not only was Sherman able to navigate miles of enemy territory, but he was able to do so while being almost completely cut off from his supply base in Atlanta. By turning the nature of military strategy on its head and removing the necessity for consistent contact with a stable base, his foraging of Confederate property and efficient wagon techniques made his army a self-sufficient and mobile force for Confederate destruction.[3]

Agricultural production map produced for Sherman to orchestrate his march (Courtesy of New York Times Online)

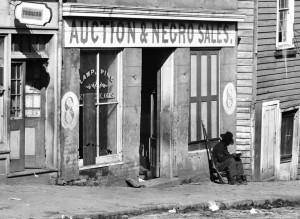

To have executed such a march across enemy territory, and without the use of today’s GPS technology, Sherman was forced to consult maps. Yet printed maps had not been created to aid a march quite like his. According to historian Sarah Schulten, Sherman requested from Joseph Kennedy, the superintendent of the census bureau, a visual representation of data that had been compiled before the war. Sherman then looked for population centers, livestock, grain and cotton production estimates as well as road and rail locations and Kennedy’s maps enumerated these figures by county for Georgia. With the help of cartographers, Kennedy integrated the census data into a map that allowed Sherman to plan the best pathways for his campaign. These marching routes cut through counties that had high foraging prospects (with lots of grain, corn, livestock, rice and tobacco) and high output of Confederate-supporting products (things that could be sold or sent to support the war effort or help the confederate civilian population, i.e. cotton and sugar) that could be burned and destroyed. These maps also charted population; both white and enslaved. Presumably including slaves in these statistics was a way to insure that Sherman was able to do some emancipating as he marched his way through the towns, cities and counties. Without these maps, Sherman knew, looking back on his march, his process of surviving off the land would have been “[subject] to blind chance.”[4] Not only were these maps essential to his understanding of the lands he occupied but also essential to insuring the success of surviving without a direct connection to his supply base.[5]

After the war, Sherman tried to quiet Northern fascination with his heroics by saying “I only regarded the march…as a ‘shift of base,’”[6] (meaning physical base of operations). Yet, it is hard to deny the morale boost and invigoration his march had for the strength of Union soldiers in their fight for the preservation of the Union. General William T. Sherman and his “March to the Sea” was a well-planned and deliberate effort to cut off the supply bases of the Confederate Army in the South and, by doing so, slowly diminish the size and strength of the rebellion. The total destruction that Sherman’s forces brought on the cities they encountered served to force their residents to suffer the harsh consequences of war, and quickly diminished the popularity of the war effort in the South. While this plan was justified in the eyes of the Union government, many white Southerners viewed the destruction the destruction and violence as atrocities. Later, this made positive relations after the war between the sections difficult to foster and even harder to maintain.

[1] William T. Sherman, Letter to Henry W. Halleck (Savannah), December 24, 1864. [Civil War Trust, Online]

[2] Noah Andre Trudeau, Southern Storm (New York, Harper Collins 2008), 536.

[3] Trudeau, 51-52.

[4] William T. Sherman, Memoirs, Book 2

[5] Susan Schulten, Sherman’s Maps, November 20, 2015 [New York Times]

[6] William T. Sherman, Memoirs, Book 2 [Southern Storm, Noah Andre Trudeau] 220.