An inevitable part of researching historical figures or events is searching through archives, which have original documents and information about people and events in the rawest form possible, unlike published scholarship, which may take some information from archival sources but ignore other important information.[1] There are also many public and private archives, which means there might be a lot of information about our topic that is scattered around. Archival documents also might not be organized in the way one needs for their research. This means that working in archives can be exciting when someone discovers something new or interesting, but also frustrating, because this takes time and patience going through many documents in many places.

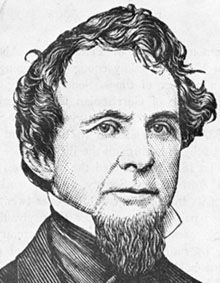

My project is on the early life and memory of Supreme Court Justice Roger Taney. One problem is that Taney did not hold on to most of his letters and other personal documents, and we don’t have a lot of his own material about his personal life.[2] Taney did begin to write a memoir that was eventually published, but we need to be careful with that source. Even if Taney thought he was being honest, he might have not been as objective as he thought he was. This means I needed to see what material we have on him that might not be in his memoir.

According to ArchiveGrid, several archives have documents on Taney.[3] Johns Hopkins University has an archive on Taney with 66 letters, and 58 of these are in the “Roger Brooke Taney letters” collection.[4] These letters are from Taney to family members, most to his son-in-law James Mason Campbell, between 1838 and 1856.[5] This was an important find, since Taney didn’t leave most of his personal letters. The Yale Collection of Western Americana, in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, also has a few letters from Taney, such as asking President Tyler to help release his relative John Taney from a Mexican jail.[6] The Library of Congress has 110 items that include writings, legal documents, letters, and other documents.[7] There are other archives with similar items, which could help us study Taney’s personal life or legal career.

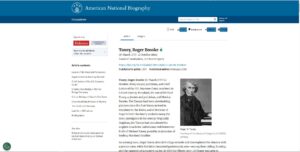

I also looked through digital archives. One of these was American National Biography, which has biographies on significant American figures. I found one for Taney that provided not only secondary sources, but also primary sources, and quotes directly from Taney himself. Considering how little primary sources there are for Taney, this was an especially good find.

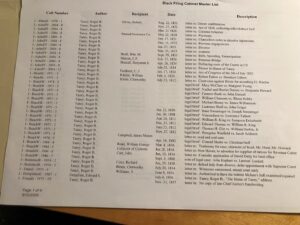

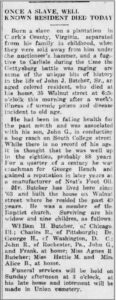

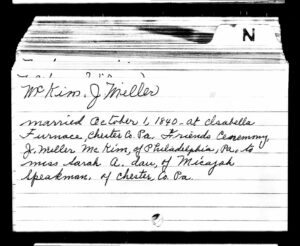

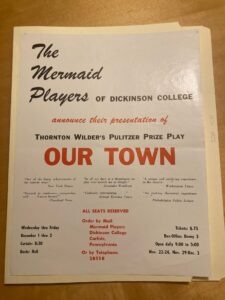

Since I don’t have time and a car to go to all these archives, I was lucky that Dickinson College has an archive on Taney, because he graduated from Dickinson and had an impact on American history. After reading some scholarship on Taney, I headed to the Dickinson College Archives on the bottom floor of the Waidner-Spahr Library. The archive receptionist knew exactly what to give me, and I received folder with nearly one hundred documents. Now I ran into another challenge of working in archives: trying to figure out which documents were useful for my project. There were many short papers from his legal work, such as a document detailing legal letters from small cases, such as divorces. There were documents on more important lawsuits, such as a case defending President Andrew Jackson from accusations of corruption. This would be useful for research on Taney’s legal work, but less on his personal life and beliefs.

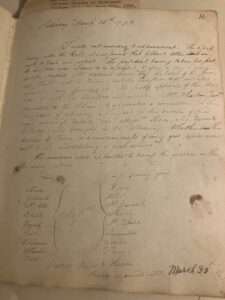

Some sources that seem more important to my project do not provide much information or only give an overview of what happened. Other sources that seem more helpful are harder to understand. For example, one source was a transcript from the Belles Lettres Literary Society, where Taney was a member. There had been some debate, but this document did not have the full text of the discussion. I asked for the original document with details about the debate, but this did not solve my problem. First, the text was faded and I could not easily make out what was written. Second, the writing style was very different than what I can read so it was incomprehensible for me to read. For now, I have to rely on the secondary transcript to make sense of this debate.

Even then, this transcript gave me some interesting information. Taney supported the execution of King Louis of France during the French Revolution[8]. This makes him seem more radical than I thought he would be, especially knowing Dred Scott. In a debate about whether wars against Native Americans were justified, Taney “was on the affirm.”[9] Now this was a discovery! Who would have thought that a young man from a slaveholding family, who would go on to write Dred Scott defending slavery, would support beheading the King of France? What happened as he got older to change his views?

One important fact I learned about Taney from this archive research is how diligent and hardworking of person he was. His teachers, such as Professor Huston, praised him as a student. The Belles Lettres Literary Society transcript shows he was very involved with debates, and he would eventually become president of the society after the previous president stepped down. This all suggests Taney was bright, active, and willing to make his views known—something which we see in his later life.

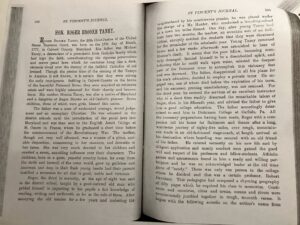

Many materials in the Dickinson archive on Taney provide detailed information and insights into his life, but they are publications, not primary sources. These authors went through some sources and put together a story about Taney. One example is a short story about Taney’s life published in 1894 in St. Vincent’s Journal.[10] This article brought to light some interesting information about Taney’s early life that I didn’t know. He was a prankster in his youth, and his father got him a tutor after his public school teacher drowned trying to walk on water.

“Hon. Roger Brooke Taney,” St. Vincent’s Journal Vol. 4, #4 (December 20, 1894): 102-108. Archives & Special Collections, Waidner-Spahr Library, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

These are interesting details for a general biography, but they do not give me much information about his views on race and slavery. However, these publications in the archive are as much about the memory of Taney as his life. How is someone supposed to know if these texts are accurate or if they are including some information and leaving other information? This does not mean this story is false, but we have to be careful with it. And this is why it is good to go to original sources in archives, to check these publications.

Overall, this research showed me that Taney was more complex than I previously thought he was. While later on he was a reactionary and supported slavery, I learned from this that when he was younger, he had more liberal views, such as opposing slavery and freeing his slaves and supporting the execution of King Louis XVI of France in the French Revolution. Through research like this, one can get a better understanding of a person and their complexities.

In the end, my first experience working in an archive was exciting, as I got to learn more about the subject of my research, Roger Taney. It was also frustrating, because going through all the documents takes time, dealing with possible bias or misinformation is a constant challenge, and making sense of some sources can take up more time than I have. But this is what we do in history: we spend more time as detectives than writers, because we need to know what happened and who people were.

[1] Zachary M. Schrag, The Princeton Guide to Historical Research (Princeton, 2021), 188.

[2] Samuel Tyler, Memoir of Roger Brooke Taney, LL.D., Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States (Baltimore: John Murphy & Co., 1872), x.

[3] “Roger Taney,” ArchiveGrid [WEB].

[4] “Roger Brooke Taney collection, 1811-1856,” Milton S. Eisenhower Library, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. [WEB]

[5] “Roger Brooke Taney letters,” Milton S. Eisenhower Library, The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. [WEB]

[6] “Letter: to President Tyler by Roger Brooke Taney, 1843 Sep 30,” Yale Collection of Western Americana, in the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University, New Haven, CN. [WEB]

[7] “Roger Brooke Taney papers, 1815-1859,” Library of Congress, Washington, DC. [WEB]

[8] Minutes of the Belles Lettres Literary Society, Vol 2, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA. p.3

[9] Minutes of the Belles Lettres Literary Society, Vol 2, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA. p.1

[10] “Hon. Roger Brooke Taney,” St. Vincent’s Journal Vol. 4, #4 (December 20, 1894): 102-108. Archives & Special Collections, Waidner-Spahr Library, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.