Why did the results of the 1860 election trigger Civil War?

Close Reading exercise

The election of 1860 was the only presidential election in American history that resulted in widespread violence. Seven states in the Deep South, led by South Carolina, refused to accept the results of the contest that elevated the new Republican Party and its nominee, Abraham Lincoln, into national power. Secession began in December 1860 (with an ordinance drafted by Dickinson College graduate John A. Inglis) and escalated into the organization of the Confederate states in February 1861 and then full blown Civil War by April when President Lincoln refused to back down in the face of assaults on Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor.

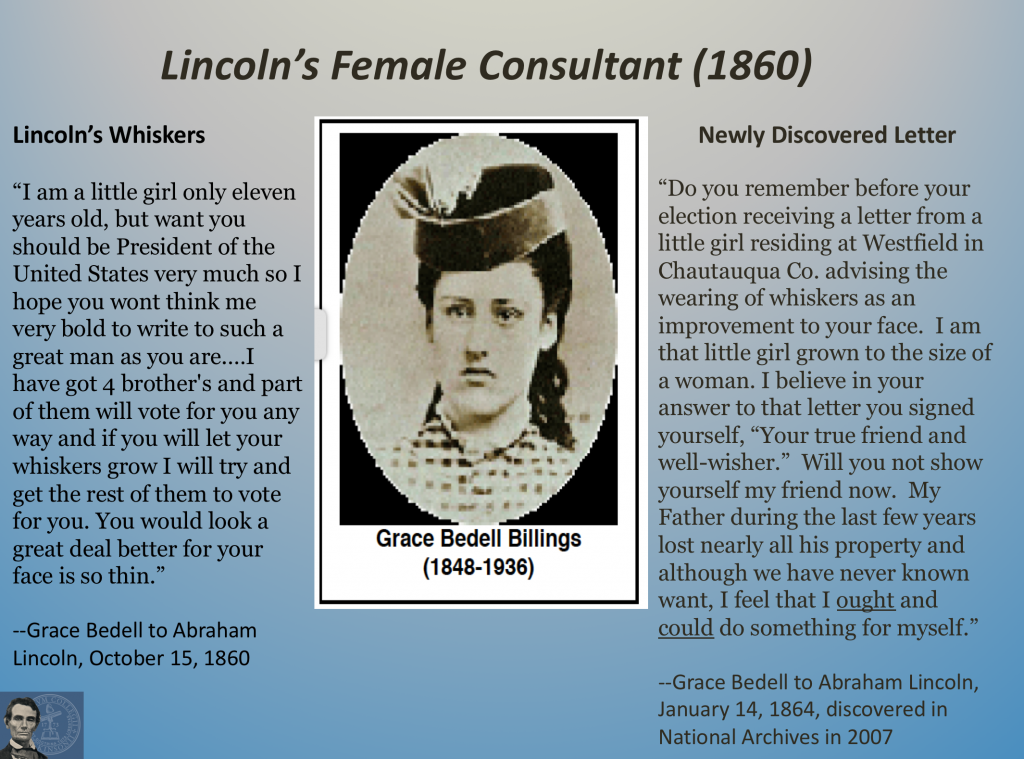

Thus, the 1860 contest stands alone in American history. Yet how should students best understand its meaning? In History 211, students will look carefully at the so-called “campaign” of Abraham Lincoln, through study of his 1859 autobiographical sketch and his October 1860 letter to a young girl named Grace Bedell. C-SPAN filmed a previous version of this particular class in 2010. You might want to check it out (and pay particular attention to the late student arriving at the beginning of the video…).

For those who need additional background on the contest, please check out the following resources:

- Chapter 13, “The Sectional Crisis,” American Yawp

- Election of 1860 results, American Presidency Project

- Election Day in Springfield, Illinois, Blog Divided

- Man of Consequence: Lincoln in the 1850s, Dickinson Survey of American History