By Sarah Aillon

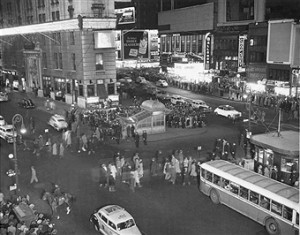

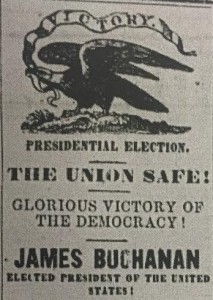

The American Democrat, November 6th, 1856.

On November 6th, 1856, the Carlisle Democrat reported that the presidential election two days prior had “passed off quietly in Cumberland County.” [1] With two exceptions, Pennsylvania had voted Democrat in every presidential election since the establishment of the United States. [2] The 1856 election was no exception. A Dickinson College graduate, James Buchanan, was the Democratic nominee in the presidential election of 1856. In the months prior to election day, Carlisle newspapers had been rallying behind his political campaign. The American Volunteer boastfully reported that “For the first time in the history of the state we have before us a Pennsylvanian as a candidate for the presidency: and not only a native Pennsylvanian, but a man who’s giant intellect and sagacious statesmanship is acknowledged throughout the Union.” [3] The political unity within the Carlisle Township, however, did not resemble the rest of the United States. Throughout the 1850’s, the debate over the expansion of slavery began polarizing political parties and the Union drastically. The Cumberland County press’ strong affiliation with the democratic party demonstrates the way in which the area itself rallied behind James Buchanan and the democratic party.

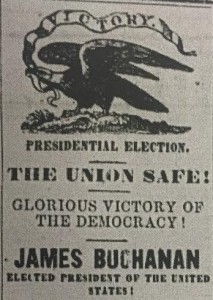

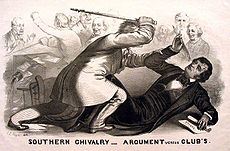

1856 political cartoon. In May 1856, South Carolina senator beat Massachusetts senator with his cane on the U.S Senate floor.

Throughout the mid-19th century, the expansion of slavery began polarizing American politics. In 1854 the territories of Kansas and Nebraska were admitted into the Union under the Kansas-Nebraska Act. [4] The Kansas-Nebraska Act granted the territories the ability to expand slavery through popular sovereignty. The act, however, violated rules regarding the expansion of slavery previously set forth in the Missouri Compromise of 1820. [5] This created much political discourse around the legality of slavery’s expansion west. Political tensions began to escalate with the mass migration of both proslavery and antislavery movements into Kansas. [6] Both of these groups sought to gain political control of Kansas. [7] The convergence of both movements within these territories created violence between the two forces. [8] The issues surrounding the violence in Kansas became one of the forefront pillars of the 1856 presidential campaign. [9]

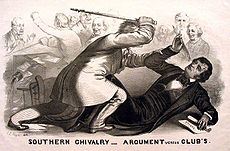

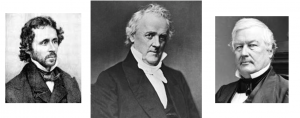

Presidental Nominees. Left, John Freemont (R), center, James Buchanan (D) and right, Millard Fillmore (A)

The democratic, republican and American party participated in the 1856 presidential election. The democratic party elected Pennsylvanian, James Buchanan as their nominee. Catering predominantly to a southern demography, democrats campaigned under the principle that the expansion of slavery should be dictated by popular sovereignty. [10] The republican party formed in 1854 to oppose the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the expansion of slavery [11]. With a majority of its supporters in the north, the party had a strong antislavery antiexpansion stance [12]. In the 1856 election, the party nominated John Fremont. The republican and democratic party were the two main political parties in the 1856 election.

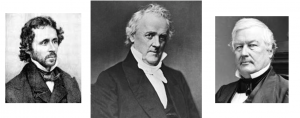

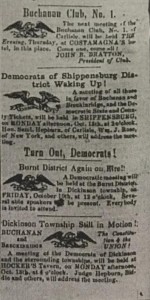

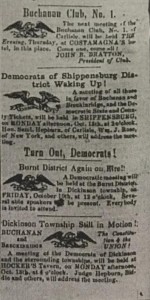

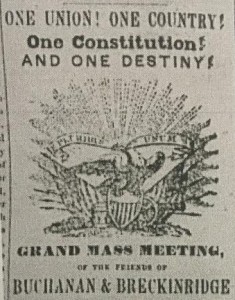

Buchan Club Advertisement, American Volunteer, October 9, 1856.

The democrats former rival, the Whig party, had disintegrated over the expansion of slavery. [13] What emerged from the political dissolution was the American Party. [14] The party chose Millard Filmore as their presidential candidate. The party did not stand on a platform relating to the expansion of slavery. Rather, they stood on a strong anti-immigration and nativist platform. [15]

Democrat James Buchanan was the Pennsylvanian favorite in the 1856 election. In the months leading to election day, “Buchanan Clubs” emerged throughout Pennsylvania. Buchanan Clubs were locally run organizations which hoped to raise support for James Buchanan. In Carlisle, these organizations began to emerge shortly after Buchanan became the democratic nominee in June of 1856. In July of 1856, the first Buchanan Club advertisement appeared in Carlisle newspaper, the American Volunteer [16]. These Buchanan Clubs had a presence in Carlisle up until the November 4th election date.

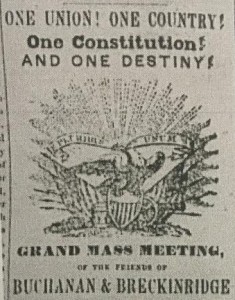

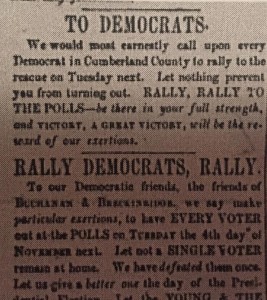

Advertisement for democratic “Mass Meeting”. American Volunteer, October 9, 1856.

Much rallying occurred for Buchanan the month before the presidential election in November. On October 9, 1856, an article in the American Volunteer was published calling for a “Mass Meeting” of democrats in the area. [17] The article rallied for full party support stating that “to gain victory in November, we must be thoroughly organized: ever borough, township, and ward in the county should be canvassed, and every Democrat vote brought to the polls.” [18] The article continues, “Come them from your workshops and your farms: come from your anvils and your looms, from your stores and from your professional engagement, and give-Saturday next to your country. A strong turnout is desirable as it will strike terror in the hearts of Disunionists and Abolitionists … show the enemy the spirit of Democracy is fully aroused.” [19] The consistent attempt to gain mass support from Carlisle democrats demonstrates how politically aligned the area was. Underneath the article calling for a mass meeting of democrats, an article titled The Great Freemont Fizzle shows the limited support for the republican presidential candidate in Cumberland County. The article reported that the “Freemonters” of the county had failed to rally a mass meeting. The passage reads ” The day arrived, and a beautiful day it was , but the people did not come- them meeting was the most complete failure.” [20]

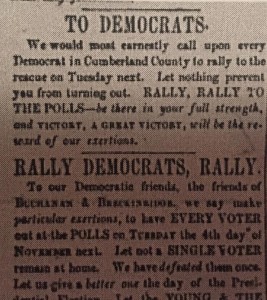

American Volunteer, October 30, 1856. Just three days before Election Day, 1856

In the weeks leading up to the 1856 election day, local Carlisle newspapers published a myriad of reminders to vote democrat in both local and state elections. After the successful election of democrat, James Buchanan, Carlisle press announced that the “Union was safe.” [21] In Cumberland County, James Buchanan received “about a 425” democratic majority. [22] Unlike other areas in the United States, Cumberland County was not tremendously polarized in 1856. Rather, Cumberland County had strong partisan ties. James Buchanan’s affiliation as a Dickinson College alumni further solidified the county’s affiliation with the democratic party. The partisan support in the county contrasts much of the political turmoil throughout the United States. The “peaceful” transition of power within Cumberland County in 1856 contrasts the national uproar that would later with the 1860 presidential election of Abraham Lincoln. [23]

Footnotes:

[1] N/a, (November 6, 1856). James Buchanan Elected President of the United States. American Democrat, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland Country Historical Collections [MICROFILM]

[2] “Presidential Elections.” Presidential Elections. Accessed November 06, 2016. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/elections.php. [WEB]

[3] N/a, (October 30, 1856). Freeman Rally to the Support of James Buchanan. American Volunteer, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Collections [MICROFILM]

[4] “Slavery and the Making of America.” PBS. 2004. Accessed November 06, 2016. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/slavery/timeline/1850.html. [WEB]

[5] “Slavery and the Making of America.” PBS. 2004. Accessed November 06, 2016. http://www.pbs.org/wnet/slavery/timeline/1850.html. [WEB]

[6] Thomas J, Balcerski. “Beards, Bachelors, and Brides: The Surprisingly Spicy Politics of the Presidential Election of 1856.” Common-Place: The Interactive Journal of Early American Life 16, no. 4, 1. Accessed November 6, 2016 [LIBGUIDES]

[7] Thomas J, Balcerski. “Beards, Bachelors, and Brides: The Surprisingly Spicy Politics of the Presidential Election of 1856.” Common-Place: The Interactive Journal of Early American Life 16, no. 4, 1. Accessed November 6, 2016 [LIBGUIDES]

[8] Thomas J, Balcerski. “Beards, Bachelors, and Brides: The Surprisingly Spicy Politics of the Presidential Election of 1856.” Common-Place: The Interactive Journal of Early American Life 16, no. 4, 1. Accessed November 6, 2016 [LIBGUIDES]

[9] Thomas J, Balcerski. “Beards, Bachelors, and Brides: The Surprisingly Spicy Politics of the Presidential Election of 1856.” Common-Place: The Interactive Journal of Early American Life 16, no. 4, 1. Accessed November 6, 2016 [LIBGUIDES]

[10] Democratic Party Platforms: “1856 Democratic Party Platform,” June 2, 1856. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=29576 [WEB]

[11] “United States Presidential Election of 1856,” Encyclopedia Britannica Online, accessed November 07, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-1856.[WEB]

[12] “United States Presidential Election of 1856,” Encyclopedia Britannica Online, accessed November 07, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-18 [WEB]

[13] “United States Presidential Election of 1856,” Encyclopedia Britannica Online, accessed November 07, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-18 [WEB]

[14] “United States Presidential Election of 1856,” Encyclopedia Britannica Online, accessed November 07, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-18 [WEB]

[15] “United States Presidential Election of 1856,” Encyclopedia Britannica Online, accessed November 07, 2016, https://www.britannica.com/event/United-States-presidential-election-of-18 [WEB]

[16] n/a, (July 10, 1856). Democratic Meeting. American Volunteer, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society [MICROFILM]

[17] n/a, (October 9, 1856). Democratic Mass Meeting. American Volunteer, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society [MICROFILM]

[18] n/a, (October 9, 1856). Democratic Mass Meeting. American Volunteer, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society [MICROFILM]

[19] n/a, (October 9, 1856). Democratic Mass Meeting. American Volunteer, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society [MICROFILM]

[20] n/a, (October 9, 1856). The Great Freemont Fizzle. American Volunteer, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland County Historical Society [MICROFILM]

[21] N/a, (November 6, 1856). James Buchanan Elected President of the United States. American Democrat, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland Country Historical Collections [MICROFILM]

[22] N/a, (November 6, 1856). James Buchanan Elected President of the United States. American Democrat, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland Country Historical Collections [MICROFILM]

[23] N/a, (November 6, 1856). James Buchanan Elected President of the United States. American Democrat, n/a. n/a, Microfilm Collection, Cumberland Country Historical Collections [MICROFILM]

Other resources used:

Magee, John L. “Southern Chivalry, Argument Versus Club’s.” Cartoon. 1856. [WEB]

Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1970. [BOOK]