- On July 25, Drew Pearson, a popular political columnist for the Washington Post, published excerpts from a leaked copy of Phillips’ final report to Roosevelt on his mission, in his daily column, “Washington Merry-Go-Round.”

Kux, Estranged Democracies (1993)

- “The story created a sensation in India and in Britain–although it cased little reaction in the United States” (36)

- “The U.S. refusal to repudiate Phillips angered the British, boosting U.S. further in India” (36)

- Phillips attempted to retire in August 1944, but Roosevelt did not accept his request in an attempt to not add to the hoopla (36)

Gould, Sikhs, Swamis, Students, and Spies (2006)

- Gould frames his text around the Pearson leak and exposing Robert Crane as the leaker “Deep Throat”

- marks the leak as a milestone in the relations between the US and India because, as according to Phillips, it “created a great commotion in England, a favorable impression here, and a burst of enthusiastic acclaim in India” (qtd. on 37)

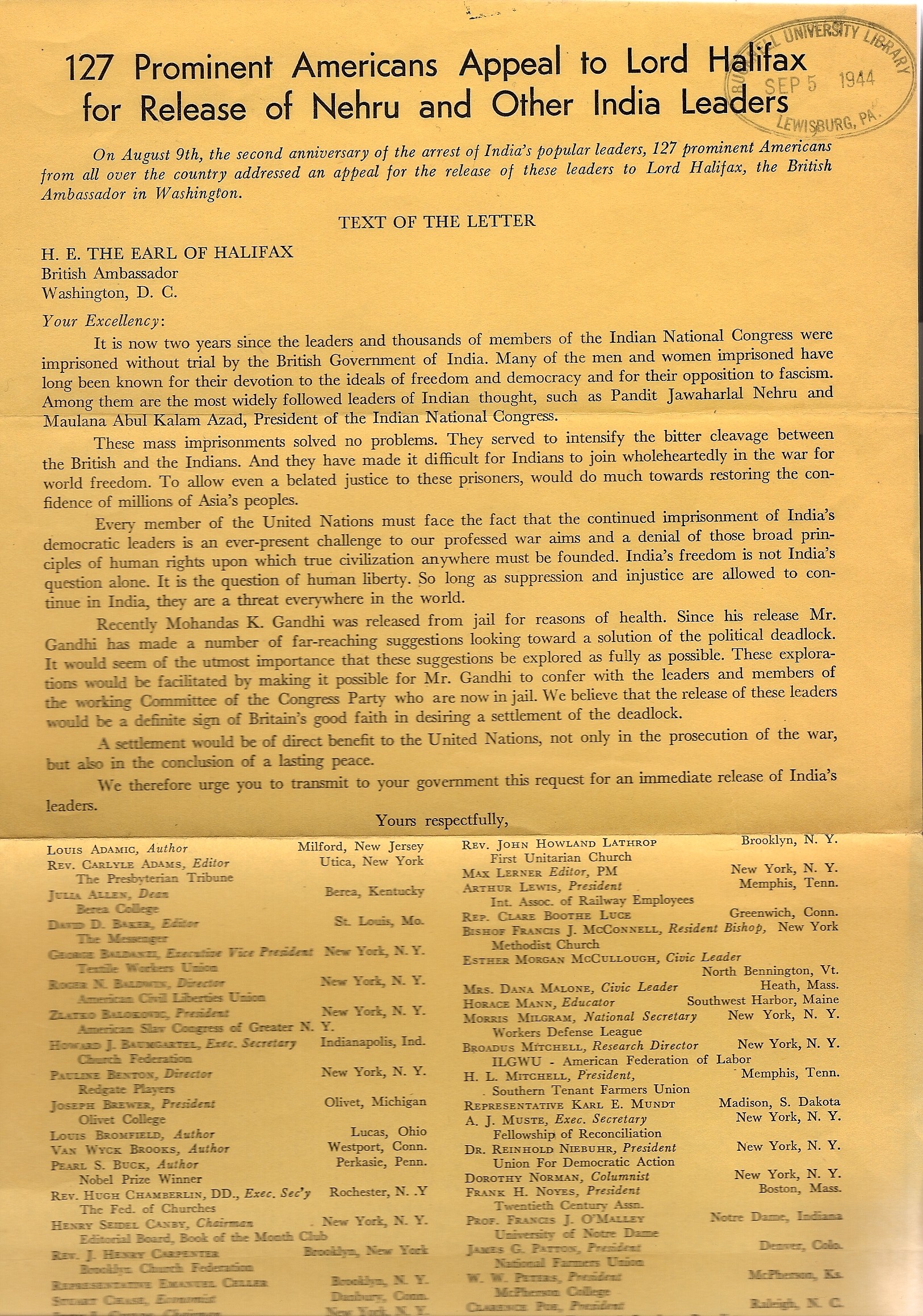

- the leak and aftermath cast a favorable glow on the US as being opposed to British imperialism for Indians, as well as strengthening the hand of the Indian-American lobbyists (38)

- describes the leak as being “consummated in a David-and-Goliath propaganda war” between the British and the Indian lobbyists, who were committed to convincing “the American people that both colonialism and racism contradicted the principles upon which the American republic was erected, as well as the ideals fro which World War II was allegedly being fought” (39)

Aldrich, Intelligence and the War Against Japan (2000)

- describes Pearson as “probably the most widely read political commentator in the United States” (148)

- While the leak created “flap” in Washington, the uproar did not extend to India or Britain: most Indian nationalists had lost hope of any American intervention in favor of their independence, and Churchill believed the leak would keep Roosevelt from raising the question of Indian independence, calling Phillips “nothing more than ‘a well-meaning ass'” (149- assessment based on intelligence papers and a letter from Churchill to Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden)

- Focuses more material on British intelligence reaction to subsequent August 1944 leaks of telegrams between Eden and the Government of India, which Pearson also published (149-150)

Hess, America Encounters India (1971)

- “the British response was immediate and definite”– wanted the U.S. gov’t to disavow Phillips’ report (143)

- “virtually ignored in the American press” but received a significant amount of attention in India (144- cites major Indian newspapers)

Phillips, Ventures in Diplomacy (1952)

- Phillips implies that he was about to facilitate discussions between the U.S. and Britain on the India issue at the time of publication, which in turn, dashed the possibility of revisiting the subject (413-414)

- The publication of Phillips’ report: “created great commotion in England, a favorable impression here, and a burst of enthusiastic acclaim in India” (389).

White, A Rising Wind (1945)

- Describes the leak as having “the highest significance” because it elucidated the arguments made by advocates of Indian independence (148)