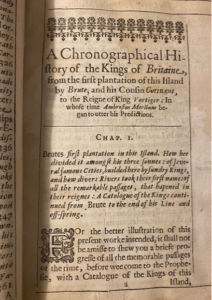

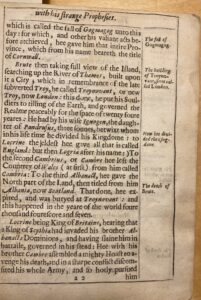

Beyond the intriguing political climates surrounding the origins of the actual printing, the copy of The Life of Merlin that I have had the chance to study has had a bit of a journey beyond the printing press (which is of course to be expected from a book created in 1641).

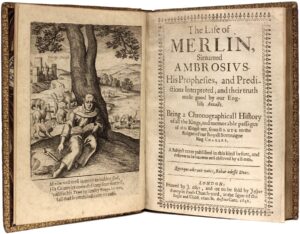

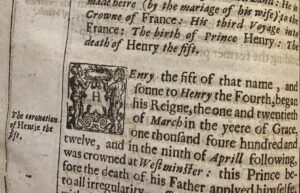

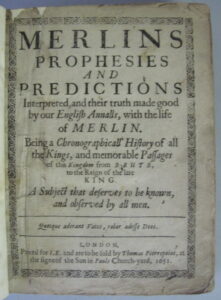

Regarding publishing, The Life of Merlin had three print runs– the original 1641 edition, a 1651 edition, and an 1812 printing. The 1651 edition is mostly a reissue, published by a bookseller named Thomas Pierrepoint at “at the singe of the Sun in Paul’s Church-yard” but makes the acknowledgement of King Charles’ death (Figure A).

Figure A. The cover page of the 1651 edition of The Life of Merlin– note that it now says “to the Reign of the late King” as opposed to King Charles. Photo from Freeman’s Auction (ninth source on Works Cited).

It’s probable that this was why the book was reprinted in the first place.

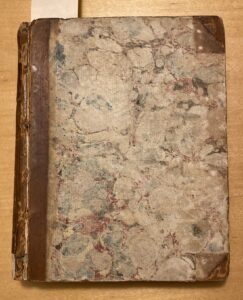

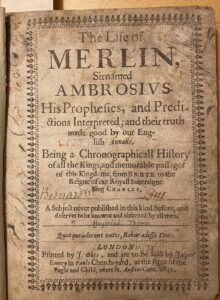

In the 1812 issue, there are stylistic changes– for example, the “Prophecies and Predictions” part of the title is in blackletter typeface now– but the same hand-marbled cover and content carry over from the previous edition (Figure B).

Figure B. The cover of an 1812 version of The Life of Merlin.

Image from Rooke Books’ seller listing.

From what I can tell, according to the listing of one such copy on the Biblio database of rare book auctions from Rookes Books, the printing is more refined in the 1812 edition. The marginalia are gone, and the text is formatted in a way more reminiscent of our modern books. There are indents, little to no ornamentations (from the previews I saw), and when quotations are done, they’re not italicized but quoted in a more modern, standardized manner. The 1812 edition was published by the Carmarthen company– by J. Evans and Messrs Lackington. This edition of the book is listed as both “very scarce” and historically “interesting,” according to the Biblio listing from Rookes Books.

If we look further into the differences between the 1812 edition and the original 1641 printing, the former is far easier to find both digitized and on databases. Additionally, Google digitized the 1812 edition onto Google Books, but there is no mention of the 1641 edition anywhere, at least not in Google’s databases.

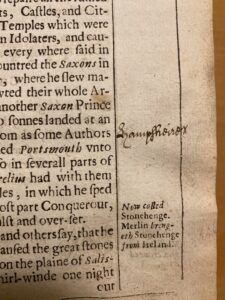

Multiple editions aren’t where the book’s journey ends– the copy of The Life of Merlin that I have has an ex-libris before the Sellers name and the dedication to Helen Gilbert. After I did a reverse image search on it, shown in Figure C, it appeared to be a coat of arms.

Figure C. The bookplate inside The Life of Merlin.

Looking at the “House of Hill” webpage on European Heraldry, the claim that it is an armorial bookplate of Rowland Clegg Hill, or the Hill family, proves true. There is still some mystique here, though—according to the images on the website, the bookplate could’ve belonged to either Rowland Hill, who lived from 1800–1875 and was the 2nd Viscount of Hill of Hawkestone and Hardwicke, or his son Rowland Clegg-Hill, the 3rd Viscount. The Hill family crest is outlined in Figure D and again on the “House of Hill” website.

Figure D. The Hill family crest/coat of arms.

Image from European Heraldry’s House of Hill.

Anne Clegg’s coat-of-arms is also somewhat adapted in the bookplate, and she is the mother of Rowland Clegg-Hill, which is why I’m unsure as to whose coat of arms this is.

Either way, the two of them were British politicians; according to the biographical entry on Rowland Hill from The History of Parliament and the biographical entry for Rowland Clegg-Hill in Prabook, both had military careers, with the 2nd Viscount serving as part of the Royal Horse Guards and eventually becoming Lord Lieutenant of the Shropshire Yeomanry and the 3rd Viscount also serving until 1879. Rowland Hill was a Tory politician who was in parliament for Shropshire from 1821–1832, and he became Baronet of Hawkstone in 1824, serving in the House of Lords in 1842. Rowland Clegg-Hill was a Conservative Member of Parliament for North Shropshire from 1857–1865. He succeeded his father in the viscountcy in 1875, becoming part of the House of Lords, but became bankrupt in 1894 with a debt of £250,000. Perhaps that’s how this book ended up at large again.

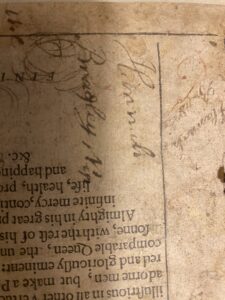

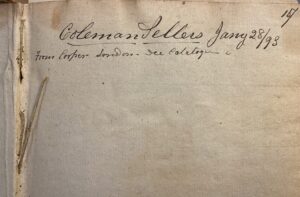

In addition to the bookplate, the frontmost pages contain the name “Coleman Sellers” and the numbers 28/98 (Figure E).

Figure E. The inked-in mention of “Coleman Sellers” at the

beginning of The Life of Merlin.

At first, I thought this was a bookseller’s company name, but it’s the family name of Charles Coleman Sellers. It’s unlikely Charles Sellers himself wrote in the book, given that if “Jany 28/98” is a date, 1998 doesn’t line up with Charles’ life and neither does 1898. I then assumed that this was something his father owned– however, the name Coleman Sellers goes back a long time. While perusing Charles Coleman Sellers’ files in the archive, I came upon a section of his will that said he was leaving a painting called “Coleman Sellers” to his son and daughter that was done by C. W. Peale. Charles Willson Peale was his great-great grandfather, a painter known best for being the first to paint portraits of George Washington. He was also the founder of one of the first American natural art and history museums, according to the National Gallery of Art’s webpage on him (listed below). If mentions of “Coleman Sellers” go back that far, it’s an old name.

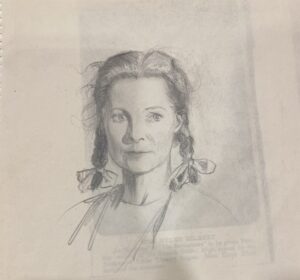

Unfortunately, there wasn’t much in Helen Gilbert’s file beyond a sketch shown in Figure F, a photo of her from junior high and a poem in a small magazine from 1925.

Figure F. A sketch of Helen Gilbert, unknown artist.

Archivist Malinda Triller told me she believed Helen Gilbert to be Sellers’ first wife. According to page on Sellers from the American National Biography, she was “an actress, poet, and author of children’s stories, whose work was published in Poetry Magazine and Sewanee Review,” and they ran a small bookstore called Tracey’s Bookstore in Hebron, Connecticut, where she was originally from (Soltis). This went on until Sellers got his job as a bibliographic librarian at Wesleyan University. In this way, the dedication of the book in her memory when donated to Dickinson College then makes sense.

Sellers’ file was significantly larger. Going through various news clipping from Dickinson regarding his job, his awards for research work and his honoring of his great-great grandfather, I uncovered the history of a very dedicated man. According to a statement issued by Sam A. Banks titled “Dickinson College Newsletter detailing Charles Coleman Sellers’ passing,” Charles Coleman Sellers was born in 1903, was educated at Haverford College and Harvard University, and came to Dickinson College in 1949 as a curator and a teacher in the fine arts. Beginning in 1956, he was librarian for 12 years. He was dedicated to preserving the history of his great-great grandfather Charles Willson Peale, and retired in 1968, but worked tirelessly to capture the history of Dickinson and beyond. He passed away on January 31st of 1980. From what I can tell, he was a meticulous librarian with a love for both books and history– it seems only right that such a book like The Life of Merlin should have ended up with him, considering it’s about both.

Beyond knowing that it was likely Mr. Sellers donated the book, I’m not entirely sure how it got here. The number attached to it meant that the book was likely added around the 1960s, which would be in line with Sellers’ retirement and subsequent passing, but I’m not sure if it ended up with the large group of appraised books from a subsequent piece of paperwork or if he donated it while he was still alive, as the donation is in his first wife’s name.

It was certainly lovely to learn about a man so dedicated to the preservation of books and history, especially after having spent time in the archives these past weeks.

Works Cited

“Armorial Bookplate of Rowland Clegg Hill, 3rd Viscount.” Flickr,

https://www.flickr.com/photos/58558794@N07/6308396557. Accessed 26 March 2023.

Banks, Sam A. “Dickinson College Newsletter detailing Charles Coleman Sellers’ passing.” Dickinson News. 11 February 1980.

“Charles Willson Peale.” National Gallery of Art, www.nga.gov/collection/artist-info.1774.html. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Heywood, Thomas. “The Life of Merlin: Digitized by Google Books.” Google Books, https://play.google.com/store/books/details/Thomas_Heywood_The_Life_of_Merlin?id=iXqNGrHlkZ4C. Accessed 26 March 2023.

“House of Hill.” European Heraldry, https://europeanheraldry.org/united-kingdom/families/families-g-l/house-hill-england/. Accessed 26 March 2023.

“Hill, Rowland (1800-1875) of Hawkstone, Salop.” History of Parliament Online, historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/18201832/member/hill-rowland-1800-1875. Accessed 15 May 2023.

“Hill History, Family Crest & Coats of Arms.” House Of Names, https://www.houseofnames.com/hill-family-crest. Accessed 26 March 2023.

Last will and testament of Charles Coleman Sellers. 14 November 1978.

“Listing of Merlin’s Prophesies and Predictions Interpreted.” Biblio, https://www.biblio.com/book/merlins-prophesies-predictions-interpreted-truthmade/d/313885539aid=vialibri&t=1&utm_source=vialibri&utm_medium=archive&utm_campaign=vialibri. Accessed 26 March 2023.

“Listing of The Life of Merlin Surnamed Ambrosius.” Biblio, https://www.biblio.com/book/life-merlin-surnamed-ambrosius-thomas-heywood/d/1363093383. Accessed 26 March 2023.

“Merlin’s Prophesies and Predictions with the Life of Merlin.” Freeman’s Auctions, https://www.freemansauction.com/auction/lot/153-1-vol-heywood-thomas-merlins-prophesies/?lot=487543&sd=1. Accessed 26 March 2023.

Mosley, Charles. Burke’s Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage. Burke’s Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003.

“Rowland Hill.” Prabook, prabook.com/web/rowland.hill/1772728. Accessed 15 May 2023.

Soltis, Carol Eaton. “Sellers, Charles Coleman (1903-1980), biographer and librarian.” American National Biography, Oxford University Press, www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1401140. Accessed 15 May 2023.

“1812 The Life of Merlin Surnamed Ambrosius.” Rooke Books, https://www.rookebooks.com/1812-the-life-of-merlin-surnamed-ambrosius-scarce-reprint-of-1641-ed-heywood. Accessed 26 March 2023.