Month: April 2022 (Page 6 of 8)

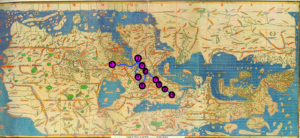

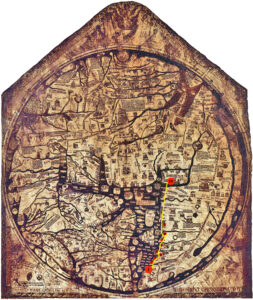

Using collected information from the fourteenth century narrative, The Travels of Ibn Battutah, and modern mapping techniques, it has been possible to map the early stages of Ibn Battutah’s pilgrimage and exploration. While one map shows Battutah’s journey through Google Earth’s digital mapping software, the other map marks his journey on a digitized copy of the Hereford Mappa Mundi. Both maps display the same ten locations that Battutah first visits, starting in Tlemcen, Morocco, and ending in Alexandria, Egypt, however each map provides a unique display of these points. Mapping the same part of Battutah’s journey on two different types of maps, one being modern and the other medieval, shows both the different purposes of each map as well as the shared characteristics that remained consistent over the span of seven hundred years.

Because the modern map uses a mercator projection while the medieval map uses a T-O projection, these two maps have different orientations and geographic features that alter the appearance of Battutah’s journey. The Hereford Mappa Mundi, which has an eastern orientation, places Tlemcen, Morocco near the bottom of the map and Alexandria, Egypt, near the middle. The digital map, however, has a northern orientation, and places Tlemcen near the left of the map and Alexandria further to the right. Although both maps show that Battutah traveled eastward, this direction of travel has more meaning on the Hereford Map due to the religious beliefs, as depicted on the map, associating an eternal “Paradise” with the East. By traveling in an upward direction, Battutah gets closer to the Garden of Eden,“Paradise”, and God/Allah, as depicted at the top of the map. The Hereford Map acts as a geographic and a spiritual reference, so it makes sense that the religious importance of this eastward movement is portrayed only on the medieval map.

The differing orientations made it difficult to translate the points from the modern map onto the medieval map, however the major water masses portrayed on both maps made this process more feasible. This section of Battutah’s journey occurred along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, so it was helpful to locate this body of water and then map the points in relation to it. Mapping the points in relation to a geographic feature results in less precise markers, but this method was necessary considering the major differences between the two maps.

The spatial distance between each of the marked points, however, remains relatively similar across the two maps. Even though the Hereford Map distorts the sizes of Asia, Africa, and Europe on a large scale, the sizes of individual countries in Africa are more realistic, at least along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, in relation to each other. Battutah passes through Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt during this section of his pilgrimage; the first eight cities he visits are more clustered together, while the last two cities he visits, Tripoli, Libya, and Alexandria, Egypt, have a greater distance between them. Both maps show that Battutah traveled the longest the distance going from Tripoli to Alexandria, and the second longest distance going from Gabes to Tripoli. This similarity shows that even when maps have different orientations or scales, it is still possible to show the general relation between locations.

The locations mapped: Tlemcen, Milyanah, Bougie, Constantine, Bône, Tunis, Sfax, Gabes, Tripoli, Alexandria

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hereford_Mappa_Mundi.jpg

Comparison between the medieval map, the Tabula Rogeriana, and the modern map, Google Maps, reveals the stark differences between the two maps that highlight the inaccuracies in the Tabula Rogeriana. The Tabula Rogeriana misinterprets much of the sizes of many bodies of water in and around the Eurasian continent. For example, on the Tabula Rogeriana, what I assuming to be the representation of the Black Sea is drawn to connect to a larger body of water that is connected to the ocean by a strait of water that goes through Northern Europe. On the Google Maps, there is no strait of water that goes through the top of the continent, though there is an ocean above the entire continent. The Black Sea does not connect to the ocean above Europe, thus revealing that travelers during this time period had yet to travel to the Northern areas of Eastern Europe and Asia and assumed the region to be just water. In addition to the areas travelers mainly had yet to venture to, most of the Mongol region in this medieval map is depicted as large bodies of water, revealing another region that most travelers had not yet reached or been able to explore and did not know of his existence. Given the Mongol region seems to be mainly untouched by other travelers, Polo presumably thought he had traveled into most of Asia because the borders of the Mongol Empire align with the Tabula Rogeriana’s drawn ending of the continent. However, though the sizes are inaccurate, the general locations of the bodies of water in the Middle East are fairly accurate. Though farther West and East the bodies of water tend to represent regions that have yet to be traveled to by Western travelers, such as Marco Polo.

Another difference worthy of note between the two maps is the drawing of the Eurasian continent. The shape of the mainland and those islands scattered within the other bodies of water within the continent on the medieval map do not match that of the modern map. The Tabula Rogeriana’s western region beyond the particular route of Marco Polo in this map excludes all of Africa and its drawing of Europe does not match the modern map’s Europe. Europe on the modern map is drawn in the shape of a dragon head with smaller regions underneath and long stretches that reach the area of this particular travel of Polo’s. The medieval map’s western region, immediately west of Polo’s depicted route, shows the shape of Spain’s country, which matches that of the modern map. Essentially, using the modern map as a template, the medieval map depicts Spain as the entire shape of the European continent which then feeds immediately into the Middle East, the location of Polo’s route. The end of Polo’s route exemplifies where medieval travelers knew to be the edges of Asia, which upon reviewing the modern map, was the center of the Middle East. Further, it seems medieval travelers assumed the Middle East was significantly closer to Europe than it was. The regions that are assumably Europe and the Middle East are drawn to be very close to each other with not much region in between, also suggesting they did also did not know the actual size of Europe as all of the modern map’s Northern Europe is not pictured on the medieval map.