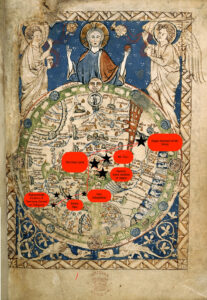

There are a plethora of differences between our modern world map and the Psaltic Mappa Mundi that Felix Fabri most likely used to trace his journey. For one, the modern world map that we use derives from satellite footage of the earth, and is therefore an accurate depiction of its landmass, water content, plates, etc. The Psaltic Map, which predates Felix Fabri’s journey to The Holy Land about 200 years, focuses less on accuracy of location and more on the importance of points relative to Jerusalem and other biblical landmarks. For example, despite their separation by large masses of water, Italy (Roma) and Jerusalem are depicted in proximity to each other, and the illustration does not depict a body of water that separates the two locations. In fact, Italy and Jerusalem are separated only by landmass on the Psaltic map, which implies that traveling from one place to the other can be accomplished on foot or on horseback, which is not the case!

In addition to the differences in accuracy and purpose between the Psaltic map and the modern world map, there is also a major difference in the maps’ orientations. Our modern world map is oriented from left (west) to right (east), and it captures lands that were undiscovered during the Middle Ages (i.e. North America). The Psaltic map, however, is circular, an attempt to depict the roundness of the earth. In addition, east is oriented at the top of the map where Jesus is depicted and Jerusalem is mapped in the center of the entire map. These were intentional choices made by the artist. East being located towards the top of the map near the deepcition of Jesus and Adam and Eve implies the region’s closeness to God, morality and purity. This ideology aligns with that of Felix Fabri, who revered places like Mt. Sinai, Mount Carmel and the Joppa Port. The farther away from the top of the map a region is, the less morally upstanding it is.