Author: rices (Page 1 of 2)

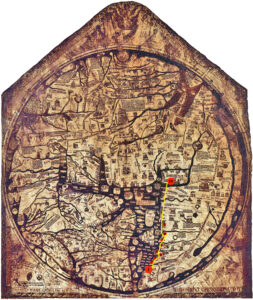

Using collected information from the fourteenth century narrative, The Travels of Ibn Battutah, and modern mapping techniques, it has been possible to map the early stages of Ibn Battutah’s pilgrimage and exploration. While one map shows Battutah’s journey through Google Earth’s digital mapping software, the other map marks his journey on a digitized copy of the Hereford Mappa Mundi. Both maps display the same ten locations that Battutah first visits, starting in Tlemcen, Morocco, and ending in Alexandria, Egypt, however each map provides a unique display of these points. Mapping the same part of Battutah’s journey on two different types of maps, one being modern and the other medieval, shows both the different purposes of each map as well as the shared characteristics that remained consistent over the span of seven hundred years.

Because the modern map uses a mercator projection while the medieval map uses a T-O projection, these two maps have different orientations and geographic features that alter the appearance of Battutah’s journey. The Hereford Mappa Mundi, which has an eastern orientation, places Tlemcen, Morocco near the bottom of the map and Alexandria, Egypt, near the middle. The digital map, however, has a northern orientation, and places Tlemcen near the left of the map and Alexandria further to the right. Although both maps show that Battutah traveled eastward, this direction of travel has more meaning on the Hereford Map due to the religious beliefs, as depicted on the map, associating an eternal “Paradise” with the East. By traveling in an upward direction, Battutah gets closer to the Garden of Eden,“Paradise”, and God/Allah, as depicted at the top of the map. The Hereford Map acts as a geographic and a spiritual reference, so it makes sense that the religious importance of this eastward movement is portrayed only on the medieval map.

The differing orientations made it difficult to translate the points from the modern map onto the medieval map, however the major water masses portrayed on both maps made this process more feasible. This section of Battutah’s journey occurred along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, so it was helpful to locate this body of water and then map the points in relation to it. Mapping the points in relation to a geographic feature results in less precise markers, but this method was necessary considering the major differences between the two maps.

The spatial distance between each of the marked points, however, remains relatively similar across the two maps. Even though the Hereford Map distorts the sizes of Asia, Africa, and Europe on a large scale, the sizes of individual countries in Africa are more realistic, at least along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, in relation to each other. Battutah passes through Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt during this section of his pilgrimage; the first eight cities he visits are more clustered together, while the last two cities he visits, Tripoli, Libya, and Alexandria, Egypt, have a greater distance between them. Both maps show that Battutah traveled the longest the distance going from Tripoli to Alexandria, and the second longest distance going from Gabes to Tripoli. This similarity shows that even when maps have different orientations or scales, it is still possible to show the general relation between locations.

The locations mapped: Tlemcen, Milyanah, Bougie, Constantine, Bône, Tunis, Sfax, Gabes, Tripoli, Alexandria

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hereford_Mappa_Mundi.jpg

After nine years of traveling, Ibn Battutah claims, through his narrative, that he had reached South India. His first few weeks in South India mainly involved making short journeys via ship from island to island, traveling along shorelines, and visiting several coastal cities. Although Battutah did not note any of these islands or their communities as being particularly important or noteworthy, he did describe in great detail the land of Mulaibar. The Mulaibar territory, also referred to as pepper county, is known for its coastal road that connects the cities Sandabur and Kawlam. Battutah notes that it usually takes travelers two months to complete the journey, but that the road is notoriously safe and hospitable for Muslims and “infidels” alike. He does, however, describe the subtle ways in which the “infidels” persecute against Muslim travelers through their enforcement of body politics. In describing the land of Mulaibar, specifically focusing on the infidels who live in it and their treatment of Muslim travelers, Battutah shows the more nuanced ways in which religious power dynamics were enforced.

When describing the road through the land of Mulaibar, Battutah supports his claim that it is a safe and hospitable journey by noting that, after every half mile, there is a wooden shed, a bench, and a water well. An infidel cares for these amenities so that they can help the travelers rest and replenish. While this initially appears to be an amicable act on part of the infidels, Battutah goes on to explain that the infidels refuse to let Muslim travelers into their homes or use vessiles when eating and drinking. Instead, the infidels serve the travelers water in their hands and food on banana leaves. If a Muslim does eat off of the infidel’s plates, bowls, or cups, then the infidel “breaks the vessels or gives them to the Muslim” (220). Here, the infidels fear a Muslim touching, and consequently contaminate, their belongings. This shows the negative connotations that the infidels associate withMuslims and their Islamic faith, since the infidels see them as a contaminant.

Because it is the Muslims’ touch that the infidels fear, the Muslim body becomes engaged in religious-based body politics. Body politics, which refers to the ways in which social or institutional power regulates the human body, puts marginalized bodies in a position that lacks autonomy and promotes oppression. Although modern body politics are often associated with race, medieval body politics were associated with religion; this is because, as explained by Geraldine Hang, religion in the Middle Ages functioned similarly to race in the Modern Ages. In the instance Battutah describes, then, the infidels use body politics to oppress and dehumanize Muslim travelers because of their religion. Although the infidels still provide assistance to Muslim travelers, and although this oppression is not as extreme or noticeable as other forms of oppression, it still enforces an unequal power dynamic between two groups of people.

By acknowledging the body politics and microaggressions faced by Muslim travelers, Battutah shows that religious oppression can take many different forms. This section of the narrative provides greater insight into the typically overlooked struggles faced by travelers, and ultimately contributes to a more detailed, more realistic representation of Battutah’s travels.

Ibn-Baṭṭūṭa Muḥammad Ibn-ʿAbdallāh, and Tim Mackintosh-Smith. The Travels of Ibn Battutah. Translated by Gibb Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen, Picador, 2002.

Eight years after Ibn Battutah’s original departure from his home in Morocco, he describes his arrival and experiences in Sind and North-Western India. In his narrative, he provides a detailed description of the town Amjari, its “infidel” inhabitants, and their cultural customs. Battutah does not provide an exact date of his arrival in Amjari, however his first accounts of Sind and North-Western India begins in mid-1333; with this in mind, and accounting for his time spent in other towns before arriving in Amjari, it is likely that he made this visit in late 1333 or early 1334. Battutah did not spend a significant amount of time in Amjari, as he only passed through the community while traveling to the near-by town of Ajudahan. Despite his limited time spent in Amjari, Battutah’s detailed descriptions and strong reactions to their cultural customs show how certain groups of people cope with painful concepts such as death, as well as his own difficulty understanding cultures different from his own.

During this small section of his narrative, Battutah writes about the ritual in Amjari to burn widowed women to death. Although the widows get to make the choice to die or not, those who do not burn themselves “dress in coarse garments”, “live with their own people in misery”, and are “despised for their lack of fidelity” ( 158). The people of Amjari ostracize and look down upon widows who do not die with their husbands and choose to continue living as their own person. Even after dying, the husband has more agency and respect than the wife. This shows that the women of Amjari are not seen as separate beings from their husbands and have limited rights and opportunities because of it. It also implies that the Amjarians have strict beliefs regarding fidelity and marriage.

While the widows who do not choose to burn to death face negative consequences, those who do choose to engage in this ritual are celebrated for their prestige and fidelity. This shows that for women, it is better to be dead than husbandless and outcasted. Battutah describes an extravagant, three-day celebration that precedes the burning of a widow. These festivities include singing, dancing, concerts, and feasts, and it gives the widows an opportunity to say their farewells. After the third day of celebration, however, the widows are covered in oil and cast themselves into a large bonfire. Despite the excitement and fanfare of the townspeople during the burning, Battutah struggles to watch the events and notes that he “had all but fallen off [his] horse” (160). Battutah’s distressed response to the burning shows that, although he promotes modesty, piety, and fidelity among women, he still sees the value of a woman’s life even in widowhood.

Battutah compares this practice to that of the “Indians” where they drown themselves in a “river of Paradise” to show their commitment to their God (160). Battutah directly compares these two practices because he struggles to understand how and why different cultures celebrate death under certain circumstances. His response is not surprising, though, considering that the Islamic faith highly values proper burials and holds specific beliefs about an afterlife.

Ibn-Baṭṭūṭa Muḥammad Ibn-ʿAbdallāh, and Tim Mackintosh-Smith. The Travels of Ibn Battutah. Translated by Gibb Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen, Picador, 2002.