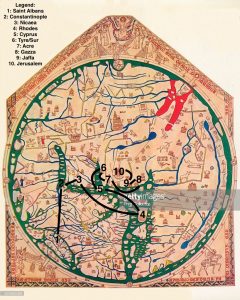

Sir John Mandeville’s journey is significantly different visually when plotted on the Hereford Mappa Mundi rather than a modern map. Most obviously, because the Hereford Mappa Mundi is oriented with east on top of the world, Mandeville seems to be traveling up and to the right rather than down and to the right. The route plotted on the modern map seems impractical and even nonsensical, in large part due to Sir John Mandeville’s misunderstandings of geography. Once plotted on the Hereford Mappa Mundi, which contains even more geographical mistakes itself, the route which is supposed to be one of the best ways to Jerusalem seems even more ridiculous. Both maps have several places where Mandeville seems to double back on himself or make a small loop, but on the modern map the loop takes place in the coastal cities of Syria and Israel, most likely due to Mandeville’s misunderstanding of how the cities are ordered down the coastline. However, on the Hereford Mappa Mundi, not only does John Mandeville not know where some of the locations he claims to have visited are located, but the map’s author does not know either. Most obviously, the labyrinth on the map that represents the island of Crete (where John Mandeville describes visiting Rhodes) is drawn much too far south in the Mediterranean, nowhere near Greece or Turkey. The island of Cyprus is not labeled at all, so I chose a larger island close to where it would realistically be located based on the modern map and called is Cyprus. I did the same with the coastal towns and cities of Syria and Israel, labelling them along the coast as closely as possible to where they were located on the modern map. The Hereford Mappa Mundi also did not have Saint Albans or Nicaea on the map, so I set them in the middle of England and Turkey, hopefully close to where they might be located. Overall, however, the Hereford Mappa Mundi is surprisingly accurate for the time. Sir John Mandeville’s ridiculous route looks very similar on both the medieval and modern map.

Author: stones (Page 1 of 2)

John Mandeville’s Journey on the Hereford Mappa Mundi

Sir John Mandeville describes the city of Babylon in a section entitled “The Way from Gaza to Babylon”. He first informs his readers that in order to travel to Babylon, they must first gain permission from the Sultan, who lives there. Mandeville seems to hold the Sultan in high regard. However, the first description Sir John Mandeville gives of Babylon is not a description of the Sultan, but a description of a church of Our Lady (Mary). He claims that Mary “lived [there] for seven years when she fled from the land of Judea in fear of King Herod.” Mandeville then goes on to list several events of religious importance that also took place in the church; he claims it to be where Jospeh stayed when he was sold by his brothers, where Nebuchadnezzar put three entirely holy children into the furnace, and the resting place of St. Barbara the virgin. However, the list is only that; a list. Mandeville does not go into great depth describing either the church or the details of its stories. Despite Sir John Mandeville’s apparent devotion to Christianity and attempting to educate others about the faith, he spends very little time on religion in what is usually primarily portrayed as a holy city, or a place of religious importance. This is in stark contrast to his other Christian location descriptions, in which he spends the majority of the time talking about Christianity. He spends only one paragraph on the religious importance of tBabylon, strongly centered around the city’s church. He spends the following twelve paragraphs describing the Sultan. It seems as though Sir John Mandeville’s reverence for the Sultan, who he claims to have lived with as a mercenary, overruled his zeal for talking about Christianity.

Sir John Mandeville’s intense admiration for the Sultan is obvious. He begins by describing the great power of the Sultan and the extent of his reach in regards to the lands he controls. He spends the next two pages describing the history of the Sultans of Egypt, much more space than he allots for Christian history. He speaks some more about the size of the Sultan’s army, and then he goes into detail about the Sultan’s life and the traditions and customs associated with it. He starts with the Sultan’s love life, pointing out that one of his wives is always Christian, but that he takes as many lovers as he wishes. Mandeville even validates the Sultan’s practice of taking all the beautiful virgins in the towns and cities that he visits, saying that he “has them detained there respectfully and with dignity”. It seems unlikely that any way the Sultan could detain all the virgins in a town would be a dignified method, but Sir John Mandeville seems convinced of the Sultan’s righteousness and nobility, despite the fact that they clearly do not share the same faith or morals. Mandeville finishes with a short description of the proper etiquette and protocol required of foreigners who wish to meet with or visit the Sultan.

It seems exceedingly strange that Sir John Mandeville, a European and an incredibly strong Christian, would prioritize information about the Sultan of Babylon rather than the Christian parts of the city, which seem to be plentiful. In addition, Mandeville does not seems as concerned or judgmental about non Christian behaviors exhibited by the Sultan; for example, he presents polygamy and the worship of the Sultan as not only acceptable but reasonable practices. This total change is strange, but the descriptions of the Sultan and his life must have seemed impressive to the author, and including them was likely an attempt to impress his audience as well.

Sir John Mandeville gives a very brief account of the Kingdom of Manzi; in fact, his summary of his supposed travels there lasts less than two pages. The Kingdom of Manzi, as he describes it, is “the best region of India”. Due to his wrongful notion that India is somehow a collection of islands, Mandeville claims that to reach this land one must voyage for several days cross the Indian Ocean. Once there, however, the Kingdom of Manzi is presented as being glorious and exotic.

Mandeville begins by describing the people of the Kingdom of Manzi. He first states that both Christians and Saracens live in the Kingdom due to its size, and later explains that its largest city houses “religious men, Christian friars, devout men”. This is strange, as Christianity in India in the Middle Ages was rare if present at all. He goes on to explain that there is no begging, because in all of the two thousand cities the kingdom holds, there is not a single poor person, which seems unlikely. He comments that the men have “wispy beards like a cat’s whiskers”, which is in keeping with his outlandish descriptions of the other strange people on the islands of India, and finishes by claiming that there are “fair-complexioned women in this region, and therefore some people call it Albania on account of its white people”. Because John Mandeville describes the Kingdom of Manzi as wonderful, pleasing and apparently perfect in every way, it can be assumed that his view of the people who live in the Kingdom of Manzi reflects what he values in people worldwide.

His first and main point is that it is a place populated by Christians, specifically devout and religious ones. This makes sense, as John Mandeville was a monk who would obviously value others under his religion. He goes into great detail describing the monastic abbey of the city of Cassay, the largest city in the Kingdom of Manzi (and apparently in “the whole world”). Mandeville apparently spends time with a monk of the abbey who is responsible for feeding the animals there, who are apparently the souls of dead men doing time in purgatory. He justifies using the leftover food in this way because the Kingdom of Manzi holds no poor people, which leads into the next claim.

Mandeville’s second claim is a little stranger; he claims that there are no poor people present in the entirety of the kingdom. Although traditionally, wealth and power are not supposed to be highly valued by Christians (especially monks, who live a humble and modest life), Mandeville clearly puts some stock in the idea of money. It is possible that his life of modesty in a monastery has caused him to look with greater fondness and even yearning to those who have more, which would explain why he references it so often throughout his narrative. It is also likely that he knows his audience will be impressed by wealth and power, and so he goes into great detail describing it, claiming that the people of Manzi have “plenty of food, and also great snakes, which they use in lavish feasts”, “fine towers”, “married women [who wear] crowns on their head”, et cetera. The strangest part of this is when Mandeville describes the animals; he claims that “the gentle and attractive animals [are] the souls of aristocrats and gentlemen, and those that are ugly [are] the souls of commoners”. This is a brutal perpetration of the elitism and classism that was common in the medieval period, but for a monk to make the claim is unusual and even contradictory to traditional Christian values.

Finally, Mandeville describes the people of the Kingdom of Manzi as being white. This is a clear sign that Mandeville bought into the idea of the “superior” white man and aversion to any people not like himself that was so common at the time. He needs the people of Manzi to be white so that it can be the greatest place on Earth in his eyes.

Sir John Mandeville ends his account with the tale of the land of Prester John. He claims Prester John is regarded as “the Emperor of India”, and that his land, called “the isle of Pentixoire”, is composed of many kingdoms of Christians. It is exceedingly clear that Mandeville has never been to India, as he begins by describing it as being composed of islands because of “great floods flowing in from Paradise”. Here, the author of Sir John Mandeville’s narrative really takes advantage of being able to describe the land as he wishes, with no contradictions from other travelers; he describes an idealistic and fanciful land full of riches and beauty, where good rules over all and the Christians are in power. He justifies the small amount of visitors by explaining that merchants find what they need in the isles of Cathay, which are closer and a much less dangerous trip than the journey to the lands of Prester John. However, Mandeville assures his readers that the lands of Prester John are nevertheless exceedingly wealthy.

John Mandeville concentrates mostly on describing the faith and piety of Prester John and the wealth and beauty his land possesses. He describes Prester John and his people as being devout Christians who believe wholeheartedly in the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, and who are loyal to one another and their faith. Even in battle, they are led by three gold crosses, who are protected by hundreds of thousands of guards. This is possible because, according to Mandeville, Prester John possesses an army composed of “innumerable men” to bring with him into battle. When not riding into battle, he carries a plain wooden cross with him, which seems to be a sign of humbleness, piety, and respect for the way his Lord died. However, despite the fact that Mandeville claims the people of Prester John’s kingdoms “set no store by material possessions”, he reports that Prester John also carries with him a vessel “full of gold and jewels, gems like rubies, sapphires, emeralds, topaz, irachite, chrysolites, and various other gems” as a symbol of his lordship and power. Sir John Mandeville then goes on to describe Prester John’s city, palace, and lands to be overflowing with exactly the type of material possession that he claims the people put no stock in. Mandeville seems to find it very important to emphasize the wealth and riches owned by the Prester John and his people. His descriptions of the gems and jewels that he apparently finds around every corner in Pentixoire seem intended to produce an awed and impressed reaction from his audience, rather than an accurate or realistic description of what a pious and humble Christian man might possess. In fact, most of Mandeville’s descriptions seem targeted towards producing a reaction rather than composing what might seem like a real world; he describes nearly everything as being either good and beautiful or evil and malevolent and therefore fought against by Prester John, and he finishes by reenforcing Prester John’s Christianity and the piousness of his people, even claiming that the kings under Prester John are all bishops, abbots, and other members of Christian clergy. Sir John Mandeville’s account of the lands of Prester John were designed to produce and amazed and dazzled reaction from his audience and connect that reaction to the idea of the greatness of Christianity.