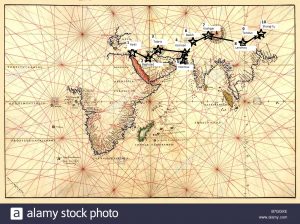

There are many obvious differences between the two maps. One visually striking difference is how much closer the points appear to be in the Medieval Map. I had a difficult time finding a portolan map that could incorporate Marco Polo’s expansive route from the Middle East to Asia. As is noticeable, the points appear to be shorter distances and are more scrunched together. In routing Marco Polo’s points of travel, I often found myself having to redo the placement of Marco Polo’s locations. I finally realized that the Medieval Map was far smaller in comparison to my modern map so my points were going to have to be much closer together than I expected. The hardest points to map were the Middle Eastern locations. The portolan map is missing some Middle Eastern countries making the Middle East much smaller. I was able to find where to place these points but I had to move the points closer together. Additionally, China appears to be much smaller in comparison to India. One reason this is so is that the portolan map’ was originally made for traveling traders, so its sole purpose was to provide detailed routes along the coastlines of these countries. Because of this, the mapping of the inside of these countries was not as much of a priority as the coastline of the Middle Eastern and Asian countries. Upon looking at this map, Marco Polo would have likely used the portolan map as a way to navigate by sea and understand where he was in reference to the traveling ports. The visual descriptions of the land within the Middle East and Asia were not correct representations, so this kind of map would not have aided in his journeys by land. Ultimately, in The Travels of Marco Polo, Marco Polo expressed his knowledge about the traveling ports and his physical location to these ports showing further evidence of how he would have used the portolan map.