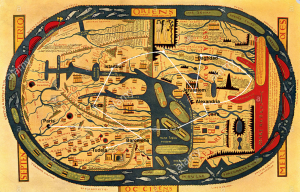

Many of the places that Polo discusses past the middle east are not visible on the Ebstorf map. Since the creator of the map resided in a monastery in Germany, they might not have had the proper source information in order to depict Asia as the vast continent it is. Instead, halfway through the landmass that is Asia, we begin getting illustrations of wonders and other religious points, such as the garden of eden. Armenia is located so far eastward, that there are no distinct representations of the Great Khan’s cities. The map would not have been useful for Polo’s travels, as it would have turned him around, however it would have been interesting to watch as monks and other map-makers attempted to make sense of Polo’s journeys. The choice to underplay the Great Khan’s power and territory could have been circumstantial – as those residing in Germany did not border his ever-growing empire the same way that Italians did – or it could have been a political choice.

Polo’s journey begins in Venice, marked by the point outside of Rome, given that that peninsula is meant to represent Italy. Rather far towards the upper-left corner of the map is a little island labeled Armenia. Here is the point for Ayas, the city that Polo describes as a gateway to the rest of Asia. Given that on this map it is rather far past the red title of Asia, the creator of this map did not agree. Back towards the center of the map is Baghdad. This markers location was chosen due to the size of the building marking this city, and its proximity to Syria, Assyria, and Arabia. Continuing to the oasis city of Talikhan, the marker is placed in unidentified land, farther east, near a mountain range, in which several beasts reside because the short description of Talikhan that Polo provides indicates that it was a smaller, less frequented city that was useful for re-supplying and a bit of trade, but not much else. Kara Khoja, the desert city that Polo travels through while crossing the Taklamakan, is marked nearby on its own island, as it would have been large enough to still gain recognition, and would have been close to other desert locations, moving towards the direction of “Asia” in general. The point marking Chagan-nor is in the upper-left corner of the map where there were several depictions of birds. Before visiting the Great Khan’s royal city in the Northeast of Asia, Polo stopped in the land of Prester John, therefore the location of Chagan-nor would need to be somewhere east enough to only be a few days ride from the kingdom of Prester John. From Chagan-nor we travel Southward in actuality, but west-ward on the map to a depiction of a king sitting upon a throne to indicate Khan-balik. The river parting around the image, mirrors the canal system of the actual city. The point representing Tandintu, in Cathay, has been placed along one of the many rivers on the way from Khan-balik to Kinsai, as the town was predominantly known for trading along the river. Kinsai is marked nearby by the large city-marker along another tributary river. Kinsai, now Hangzhou, was known for its canals, bridges, and lakes, which made it the most beautiful and prosperous city in Southern China. We circle back around to what could be the coast, given the river depicted travels from Northern Asia through India, to the southern seas, where there is a large city marker that is possibly Fu-chau – the city from which Polo departs Cathay and the Great Khan’s realm, and travels into Southeast Asia and the Pacific Islands. Finally, the point for Java has been placed in the section of the map that was lost over time, as none of the islands past the the red title of “India” were significantly larger than the others before reaching African nations.

The map demonstrates the confusion of Asian geography at the time of Polo’s travels. While a merchant would have had access to more accurate information, the inability of T-O maps to translate actual distances or locations explains a lot of fears about traveling. The map’s spacial understanding of the world is lacking, and many points had to be approximated, however it provides insight to what a great task Polo’s adventures would have been viewed as. The journey from Venice to Armenia alone looks incredibly far and difficult. The beasts illustrated in the deserts demonstrate the fear of lands that Europeans did not know much about. The depiction of the Great Khan as something resembling a European King shows the desire of Europeans to believe that the Great Khan was truly just and would not attack them.