Personally, the Malaga experience is the crowning point of my trip to the Mediterranean. Despite the fact that I do not speak Spanish at all, for me this part of the trip is where the most amount of cultural exchange happened and the most complete cultural immersion took place. What I derived from this whole experience is the conclusion that Spain is an intercultural society which respects difference and values diversity. The cultural experience started as soon as I arrived in Malaga, Spain. All of us got excited about the abundant nice restaurants and bars within arms’ reach, and soon we were out among the people sitting leisurely in the warm afternoon, enjoying rich hot chocolate, a glass of Sangria or delicious Tapas. To me, sitting in one of those places is in itself a unique Spanish experience, when good-looking Spanish young men and women were lightly passing by, when people around me were uttering the beautiful sounds unique to Spanish language, when street-performers were singing, playing guitars or an accordion around me, and when the aroma of calamari and paella was filling my nostrils… Without the many afternoons or late evenings sitting in those little outdoor restaurants with local Spaniards, my Malaga experiences wouldn’t have been as full and enriching. I felt I was included in those local people’s life in such a special way – by being in one of their sunlit afternoons. Perhaps I, a Chinese girl sitting among mostly Caucasian people, was also a subject of observation by some people around me? I do not know.

Besides the implicit cultural exchange on the streets or in the little restaurants, my communication with my host mom, Stella, was also a wonderful experience. She spoke a lot about the Spanish economic crisis and the predicaments of many Spanish people. She used to work in a bar and later as an administrator, but during the crisis she lost her job and now she cleans houses. Therefore she hosted students in order to make some extra money. However, despite the fact that she was not wealthy, she did her best to make our stay as comfortable as possible. The best part of my interaction with her started after our program ended on March 22, when almost all of my friends and professors had left Malaga and I was left by myself to communicate with the few Spanish words I know. However I did not feel lonely at all. With the help of GoogleTranslate and body language, Stella and I had a great time together. We taught each other languages and told each other about our own lives. Her openness and graciousness made my few days there unforgettable. When I left on 4:00 am in the morning of March 26th, Stella accompanied me to the taxi and told the driver to take good care of her “little baby.” It is truly wonderful to establish friendship across cultural and language barriers.

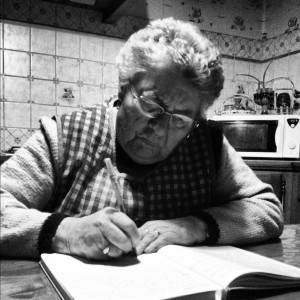

My Host Mom Stella (Left) and me (right)

Furthermore, the academic and social interactions we had with professors at the University of Malaga and with social activists in various NGOs only confirmed the sense of inclusiveness and welcome I have felt by living in Malaga. From Professor Rafael Durán Mufioz’s lecture on migration and diversity policies, we learned a lot about Spain’s approach to cultural diversity. According to Prof. Rafael, Interculturalism as an approach is favored above Multiculturalism and Assimilationism, and Spanish society is developing towards mutual respect by setting the objectives to promote welcoming policies and full-integration of immigrants. Another relevant event is the seminar we attended that was held by the NGO: The Moroccan Association for the Integration of Immigrants. Another professor from the University of Malaga: Victor Solbes condemned the existence of borders upon which racism, xenophobia, and neo-Nazism develop. He pointed out that the current education in Spain was accentuating the differentiation between “us” and “them”, and unless intercultural education for the whole society is established in Spain, people’s mind-set could hardly be changed. At the end Prof. Solbes said that intercultural education sounds hard and utopian, but it is something the society should aim for. His call for the creation of a society “from an ethnic point of view” speaks for many Spaniards who are working hard to achieve an ethnically harmonious society, an effort we felt and witnessed in our 10 days in Malaga.

Malaga, Spain as a whole gave me a different feeling. For me it was an environment of openness and inclusiveness and a sense of dynamic energy: the sense that some positive changes are actively taking place. Although each society has its own problems related to the integration of immigrants, after staying in Malaga, I believe that the barriers Spain is facing are not insurmountable. Granting enough time and with the efforts of some members of the society, Spain could eventually overcome various barriers and achieve the goal of an intercultural society.