From the radiation of its food to the radiation of its rivers, Russia has built itself into a competitive nuclear power through a tumultuous history of trial and error.[1] Much of the initial funding for Soviet nuclear energy came in an effort to match the United States’ atomic project. But, after developing “the bomb”, nuclear resources in the USSR were applied to a number of areas. These often gave poor results. From such failures, modern Russia has striven to provide a nuclear industry that is safe, clean, and sustainable. In fact, the head of Rosatom’s used fuel management has set a goal of 100% efficiency in the company’s fuel cycle; where all spent fuel is reprocessed into the system — no waste.[4] To understand these, at first, outlandish expectations, we should consider the damages and adaptations that the industry has incurred since its inception in the 1940s.

In the earliest days of the Soviet nuclear industry, one of the most practiced efforts was the irradiation of food. This gave food stuffs a much longer shelf life and they exhibited fewer incidents of contamination due to bacteria or spoiling. But, this also exposed many citizens to harmful levels of radiation after sustained consumption.

In an effort to appease the growing “green movements” in the Soviet Union, Stalin once pursued an aggressive hydro-electric policy. To map the currents in possible rivers, the Soviets had opted to use radioactive isotopes instead of foreign nutrients. These isotopes gave far more accurate readings than the nutrients which would dissolve more quickly in the water. Unfortunately, these tests also irradiated the sites on which they were conducted.

In an effort to store industrial byproducts in a safe manner, the Soviet Union began to put barrels of waste under the Arctic ice. They thought that the metal barrels would isolate the waste from the environment while still allowing the nuclear waste to cool down. Now, Russia has begun to take responsibility for the incident and is trying to excavate them from beneath the ice. The trouble here is that the area is inaccessible during from late fall to spring as the ice begins to freeze too thick for Russia’s icebreakers.

Many of the efforts during the Soviet era to remedy environmental damage came as a result of grass root environmental movements. Following Gorbachev’s “glas’nost”, many citizens began speaking out.[2] Other factors, such as better education and a growing middle-class, have also been credited with influencing environmental activism in the late Soviet period.[3] What is interesting is how the green movements began to recede after  the collapse of the Soviet Union. Henry, in Red to Green, implies this is the product of government assimilation of environmental practices. In the 1990s, the Russian Green Party is established and large funds are diverted to repair environmental damages from the Soviet era. Russia has also taken responsibility for much of the Bloc’s environmental damages. Perhaps this accountability has made the green Soviet activists obsolete. In modern Russia there are still environmental hazards; the significant decline in incidents is still watched closely by the green organizations. But, the grass root aspect of Soviet environmentalism has lessened.

the collapse of the Soviet Union. Henry, in Red to Green, implies this is the product of government assimilation of environmental practices. In the 1990s, the Russian Green Party is established and large funds are diverted to repair environmental damages from the Soviet era. Russia has also taken responsibility for much of the Bloc’s environmental damages. Perhaps this accountability has made the green Soviet activists obsolete. In modern Russia there are still environmental hazards; the significant decline in incidents is still watched closely by the green organizations. But, the grass root aspect of Soviet environmentalism has lessened.

Reckless practices by the nuclear industry created a strong green movement in the USSR which survives, in some form, in Russia today. Many of these citizen whistle-blowers were responsible for stopping projects, such as the irradiation of food, which tested nuclear  potential on ignorant Soviet citizens. The Chernobyl incident, though another blunder by the Soviet Union, also served to shape the young nuclear industry into a safer and better regulated industry than many other nations’. From the 1950s into the 1980s the USSR had been storing waste in containment pools on-site and burying large amounts in underground containment centers. Both of these practices were accepted by many Western agencies as well. But, after the international community began investigating Chernobyl, citizens began reporting violations of Soviet nuclear law in the areas around the containment sites. With international pressure, the USSR reformed their waste storage practices into secure and modern facilities based in Siberia.[4] These projects reflect much of the work regarding the Yucca Mountains in the United States.

potential on ignorant Soviet citizens. The Chernobyl incident, though another blunder by the Soviet Union, also served to shape the young nuclear industry into a safer and better regulated industry than many other nations’. From the 1950s into the 1980s the USSR had been storing waste in containment pools on-site and burying large amounts in underground containment centers. Both of these practices were accepted by many Western agencies as well. But, after the international community began investigating Chernobyl, citizens began reporting violations of Soviet nuclear law in the areas around the containment sites. With international pressure, the USSR reformed their waste storage practices into secure and modern facilities based in Siberia.[4] These projects reflect much of the work regarding the Yucca Mountains in the United States.

Here is a video detailing Russia's modern nuclear industry.

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-2iZt-K6Nao” title=”A%20short%20video%20about%20Russia%27s%20modern%20nuclear%20program.”]

Given these policy revisions, much of the pre-Chernobyl nuclear damage was left unattended until the fall of the Soviet Union. As one of its efforts to become a respectable world power, Russia began funding massive environmental clean-up projects. These are costing the country billions of rubles and figures in the nuclear industry are now stressing the economic efficiency of leak prevention and safety. In recent agreements between nuclear countries, Russia has been designated a stable recycler of nuclear waste.[5] This has given Russia the recognition of a safe and efficient destination; a safer and more efficient option than other nuclear powers, such as the United States.

Currently, Russian methods of handling nuclear waste are very similar to other nuclear countries in the West. The policies include water-submersion or dry-holding pools on site of many reactors. Without the ability to process the mass quantities of waste, spent nuclear fuel is building up in many Western countries. Russia’s nuclear industry is currently able to process 2,500 tonnes of waste each year by reprocessing spent nuclear waste so it can be utilized in the generation of more energy. The current series of reactors are designed to consume primarily ‘fresh’ uranium.[6] But, there are already a number of BN-800 and VVER-1200 series reactors, designed to consume primarily re-purposed uranium, which are nearing the end of their construction. These will make the possibility of a Russian founded Global Nuclear Energy network a viable option for energy sustainability in Eurasia.

The opening to this episode of Spotlight gives a short biography on Rosatom in Russia today.

An agreement signed in 2000 between the U.S. Department of Energy and Russia’s Federal Atomic Energy Agency, Rosatom, laid the foundation for disposal of spent U.S. waste and weaponized uranium in Russia in exchange for funds to enhance the country’s nuclear industry.[7] This increased responsibility for disposal of nuclear waste has galvanized the industry to produce such models as the BN-800 to meet growing global demand for Russia’s reprocessing ability. Rosatom has, also, laid the goal of having a 100 percent sustainable nuclear industry by 2020.[8] This program would increase domestic demand, too. As it stands, Russia is reprocessing much of the United States’ nuclear waste and storing it for later use in the BN-800 and VVER-1200 reactors in addition to

purchasing and developing its own ‘fresh’ uranium. Effectively, Russia appears to be stockpiling used uranium (potential energy) which the U.S. is paying for the country to import. This is a very effective economic policy for Russia, but this system is dependent on developing the consumption of reprocessed nuclear waste instead of increasing output of energy. Many of these new reactor series had their designs and construction paid for by the 2000 Agreement. Because the emphasis was on the consumption of United States’ waste and not expanding Russian energy supply, this dictated the evolution of the Russian nuclear energy industry. Also telling is that the United States is the country exporting its waste to Russia. The United States has long been a leading nuclear power when considering total energy output and uranium consumption. This would make the United States one of the largest waste producers then, as well. That the United States has to purchase the services of another nuclear power is interesting, and Russia is using this to its advantage.

purchasing and developing its own ‘fresh’ uranium. Effectively, Russia appears to be stockpiling used uranium (potential energy) which the U.S. is paying for the country to import. This is a very effective economic policy for Russia, but this system is dependent on developing the consumption of reprocessed nuclear waste instead of increasing output of energy. Many of these new reactor series had their designs and construction paid for by the 2000 Agreement. Because the emphasis was on the consumption of United States’ waste and not expanding Russian energy supply, this dictated the evolution of the Russian nuclear energy industry. Also telling is that the United States is the country exporting its waste to Russia. The United States has long been a leading nuclear power when considering total energy output and uranium consumption. This would make the United States one of the largest waste producers then, as well. That the United States has to purchase the services of another nuclear power is interesting, and Russia is using this to its advantage.

A report by the Center for Strategic and International Studies prescribes a “Decade of Stabilization” in post-Soviet Russia ending in a loosely planed international nuclear energy network.[9] This plan prescribes foreign powers’ purchase of nuclear plant in post-Soviet states; most being maintained by France, United States, and Germany. The outlines for this transition have strong imperialist leanings by giving such domestic influence to foreign powers, but the idea is something that Rosatom seems keen on.[10] Granted in Rosatom’s plan, Already Russia is one of the largest energy providers in Eastern Europe, holding a large supply of fossil fuels and other raw materials. If Russia establishes a global nuclear energy market, its energy exports will most likely increase. Russia has begun reaching out to other nuclear powers, offering itself as a viable disposer of nuclear waste. If Russia successfully transitions to a nuclear industry which largely consumes the reprocessed nuclear wastes of other countries, then Russia will establish itself as both an energy producer and as a nuclear waste disposer.

By establishing a global nuclear network, Russia will have a larger market for its nuclear energy and its waste disposal. In a global market in which Russia is the primary disposer of nuclear waste, Russia would control the costs of its competition by influencing overhead costs of waste disposal. At the same time, Russia would be able to continue producing energy for the world market primarily from the waste that it is being paid to import by other countries.

Aside from Russian economic gains, all partners in a global nuclear energy network would benefit from Russia’s specialization in nuclear waste consumption. Russia is developing reactors focused on waste consumption and not energy production, while other countries are trying to maximize energy output in their nuclear industries. By joining a global network each country will be able to utilize the specializations of the other countries, improving the efficiency (and, ultimately, the sustainability) of each independent nuclear agency.

While Russia’s nuclear agency was founded on the unattainable goals set in the Soviet era, the mistakes made during its infancy has helped mature this field to one of the most developed in the world. While there is still evidence of its grandiose mentality, as evidenced by its floating fleet of nuclear reactors, nuclear energy in Russia is kept in reasonable check by better government regulation and an attentive population. Now, even the government’s Rosatom is helping the population stay informed on the nuclear conditions in Russia. Recently, they launched a map on their site fed by real-time radiation readings from around each nuclear plant. This site is public and open to continuous access. After the events of Chernobyl and other nuclear incidents like it, the nuclear industry has had to work to alleviate global and domestic concerns. If we consider how the international community has pursued nuclear partnerships with Russia, it seems safe to say that the industry has succeeded. Now, when we consider Russia’s nuclear industry, it may seem that “100%” efficiency might not be as far a reach as we thought.

While Russia’s nuclear agency was founded on the unattainable goals set in the Soviet era, the mistakes made during its infancy has helped mature this field to one of the most developed in the world. While there is still evidence of its grandiose mentality, as evidenced by its floating fleet of nuclear reactors, nuclear energy in Russia is kept in reasonable check by better government regulation and an attentive population. Now, even the government’s Rosatom is helping the population stay informed on the nuclear conditions in Russia. Recently, they launched a map on their site fed by real-time radiation readings from around each nuclear plant. This site is public and open to continuous access. After the events of Chernobyl and other nuclear incidents like it, the nuclear industry has had to work to alleviate global and domestic concerns. If we consider how the international community has pursued nuclear partnerships with Russia, it seems safe to say that the industry has succeeded. Now, when we consider Russia’s nuclear industry, it may seem that “100%” efficiency might not be as far a reach as we thought.

[1] Paul R. Josephson, Red Atom: Russia’s Nuclear Program from Stalin to Today, 146-166.

[2] Laura A. Henry, Red to Green: Environmental Activism in Post-Soviet Russia, 39-40.

[3] Karl Qualls, “Chernobyl and Ecocide,” Class lecture, Russia – Quest for the Modern from Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA, November 25 2013.

[4] World Nuclear Association, “Russia’s Nuclear Fuel Cycle.”

[5] Guy Lunsford, “Status of Russian Plutonium Disposition,” Proceedings of the Institute of Nuclear Matierials Management.

[6] Here I use ‘fresh’ to mean this is its first cycle of consumption, not yet reprocessed uranium.

[7] Guy Lunsford, “Status of Russian Plutonium Disposition,” Proceedings of the Institute of Nuclear Matierials Management.

[8] World Nuclear Association. Nuclear Power in Russia. Last modified September 2013.

[9] Robert Ebel, ed., Nuclear Energy Safety Challenges in the Former Soviet Union: A Consensus Report of the CSIS Congressional Study Group on Nuclear Energy Safety Challenges in the Former Soviet Union.

[10] World Nuclear Association. Russia’s Nuclear Fuel Cycle. Last modified August 23, 2013.

Full bibliographyhere.

Do you think any countries have any reticence towards supplying their nuclear waste to Russia, given the short and long term effects of Chernobyl? Has the development of Russia’s nuclear waste industry come so far that it could be considered better than the United State’s disposal of nuclear waste? It’s very interesting to see the change in Russian nuclear policies post-Chernobyl and their drastic improvement in the disposal of nuclear waste.

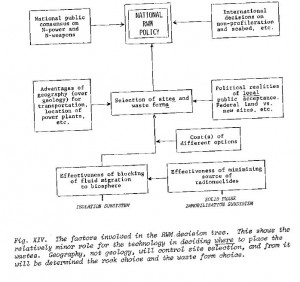

My project tries to allude to what you were getting at in your response; that Russia’s program is superior to the United States’ in some ways. I would argue that Russia has come so far in the time since Chernobyl. It was such a dramatic event that the global community responded to the USSR’s nuclear regulation. Given how much the industry has had to adapt and yet be careful of the wary public watching, I would say that it should not be surprising that Russia has emerged as a top nuclear power. I suggest you look at my third diagram where it shows a relation between public trust/education with regards to (1) legislation and (2) existing technology and safety.

Here is a recent article from NPR on the nuclear disarmament agreement which is supplying Russia with much of its weaponized uranium to be reprocessed, but from a U.S. perspective.

http://goo.gl/Bq4oVk

Why would the “irradiation of food” have exposed the populace to radioactivity? To my knowledge, gamma irradiation of normal foodstuffs does not induce nuclear chemical reactions that “enrich” the food with radioactive nuclides by transforming normal isotopes like the irradiation with e.g. alpha particles or neutrons would. Rather the drawbacks are often that the food degenerates just as with heat treatment or starts tasting “funny”. However, that Rosatom will try and adopt a fully closed fuel cycle and thus “no waste” policy should be treated with suspicion. So far any such attempts at e.g. transmutation have been as elusive as the use of fusion – all these projects are to mature in the next fifty years. When these fifty years are reached then it’s another fifty.