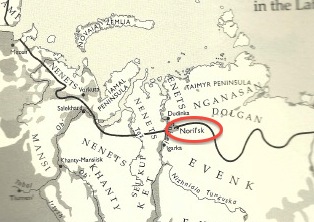

In the early twentieth century the most effective means of traveling the country was by rail systems. Because of the rails already set in place throughout Russia the logical way to reach the people was to use the trains. The first of the trains to reach the isolated peasantry was know as “Lenin’s train.”[2] This train was made up of 15 cars and “decorated with paintings in bright colors, with forceful and unmistakably revolutionary inscriptions.”[3] It is important to note, that the officials onboard the train were members of branches of the “people’s Commissariat.”[4] These men would distribute masses of pamphlets and readings free of charge to the people, as well as answer questions and advise on issues concerning the population. This was a powerful tool for the Soviet government to use, as the population will feel heard, and important to the government. This in turn will promote less resistance to newer ideas and obedience. The feeling of solidarity between the government and the workers was to be fostered in this way.

The success of such trains in spreading soviet propaganda prompted the creation of three further trains, with different routs that would bring the word of the “Revolution” to the “most hidden nooks of Soviet Russia.”[5] These propaganda trains would be responsible for returning the wishes of the people to the government and create an environment where capitalist imperialism would be unable to return to the minds of the population.

[1] Hoffmann, “European Modernity and Soviet Socialism” in Hoffmann and Kotsonis, eds., Russian Modernity: Politics, Knowledge, Practices (NY: St. Martin’s, 2000), 245-260.

[2] Iakov Okunev, A New Way for Culture Propaganda. 1919

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Agit-train October Revolution / Vertov-Collection, Austrian Film Museum

Perestroika and glasnost were terms Gorbachev used to embody his cultural reforms and openness to Western influence. The Chinese, too, had a period of openness. In 1956 Mao said that, “The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science.” This “100 Flowers Movement” was ended in 1957 with political persecutions. Both Communist powers handled political dissonance in the second half of the 20th century differently, with the USSR embracing and the Chinese silencing controversy. Though, to look at it all now, the USSR has been disbanded and China is still heavily controlled by a limited ruling class.

Perestroika and glasnost were terms Gorbachev used to embody his cultural reforms and openness to Western influence. The Chinese, too, had a period of openness. In 1956 Mao said that, “The policy of letting a hundred flowers bloom and a hundred schools of thought contend is designed to promote the flourishing of the arts and the progress of science.” This “100 Flowers Movement” was ended in 1957 with political persecutions. Both Communist powers handled political dissonance in the second half of the 20th century differently, with the USSR embracing and the Chinese silencing controversy. Though, to look at it all now, the USSR has been disbanded and China is still heavily controlled by a limited ruling class.