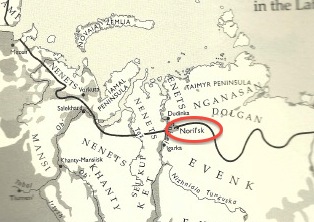

Early in the Soviet era, the government paid little attention to the indigenous tribes of Siberia and did not take into account whether their policies for modernization would have a negative effect on the native peoples. Collectivization and the push for industrialization directly affected the tribes’ economic activity, traditional lifestyle, and the environment in which they lived. Industrialization took place across the Soviet Union, however I have chosen to focus on the city of Noril’sk, located in Krasnoyarsk Krai in northern Siberia, between the Yenisei River and the Taimyr Peninsula. Four main indigenous groups converge in the area of Noril’sk; these groups are the Dolgan, the Nenets, the Nganasan, and the Evenk people. As a result of Soviet collectivization and industrialization policies of the mid-twentieth century, the traditional culture of these indigenous groups altered or faded considerably.

Here is a map showing the geographical location of Noril’sk:

Source: www.thenytimes.com

A key component of analyzing these policies and their effects on these four tribes is to consider the sustainability of these policies with regards to both the environment and the tribes’ traditional ways of life. I would like to clarify that I am defining sustainability as “long-term cultural, economic and environmental health and vitality….together with the importance of linking our social, financial and environmental well-being.” This definition comes from the organization Sustainable Seattle.[1] I argue that Soviet policy towards the indigenous tribes of Siberia in the twentieth century did not promote long-term cultural, economic or environmental vitality, and were therefore unsustainable and unsupportive for the indigenous clans of the region.

Below is a map showing the location of Evenk, Dolgan, Nenet and Nganasan territory relative to Noril’sk and to each other:

The map above shows that Noril’sk serves as a sort of epicenter for these four groups: the Dolgans, Nenets, Nganasans, and Evenks. To learn more about a specific group please click the hyperlinks for further reading. Not only are these four clans close in proximity, but also—like many Siberian tribes—each clan has historically depended on reindeer hunting or herding for their economic livelihood. This does not mean these groups are all the same; they descend from different Eurasian or East Asian ethnic groups and each speak their own native language, among other differences. That being said, each clan experienced similar difficulties adjusting their traditional lifestyles during collectivization and industrialization. There are many ways in which the Soviet Union altered the lives of tribal people in Siberia; collectivization and industrialization are simply the two policies I have chosen to analyze.