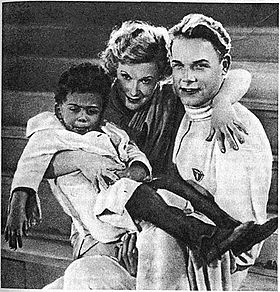

The film Circus, produced by the Soviet Union in 1936, was made in order to propagate the Union’s ideals and acceptance of all nationalities. The main hero, Marion Dixon, is chased out of the United States because of racial intolerance against her black son, Jimmy. Marion stumbles across Fronk Kneishitz, a wealthy German, who offers to take her traveling around the world and conceal the identity of her son in order to avoid persecution. Marion and Fronk Kneishitz end up on tour in Russia, where she soon meets an exemplary Soviet man, Martinov, and falls in love with him. Ludvig, the circus director, has hired Martinov to create an act to be even greater than the exotic Marion. Fronk Kneishitz becomes jealous of Marion’s affection for Martinov, and he threatens to reveal her secret at every turn in order to keep Marion under his influence. Eventually Fronk Kneishitz cannot keep Martinov and Marino apart, and out of jealousy he reveals Jimmy in font of a crowded circus performance, shaming Marion. However, the crowd and Ludvig unexpectedly embrace Jimmy, passing him throughout the crowd to keep him safe from Fronk Kneishitz. As Jimmy gets passed along, he is sung a lullaby by each nationality who holds him, in their native tongue. When Ludvig is returned Jimmy he says to Fronk Kneishitz, “In our country we love all kinds”, announcing that nationality doesn’t define a person in the Soviet Union. ((Circus, Grigori Aleksandrov and Isidor Simkov, 1936)) Martinov, Marion and Jimmy happily unite and the movie closes with a patriotic march in the Red Square proudly waving a banner with Stalin’s face on it.

Circus is uncharacteristic of the majority of Russian and Soviet films that I have seen, in that it has a generally joyous ending. Russian films tend to depict the realities of life and rarely sugarcoat these truths. The film was released in 1936, shortly after Stalin’s Five-year plan, and as a result it was a time of low morale across the nation from harsh conditions and a lack of daily necessities. Circus is an attempt to gloss over the hardships of life and inspire nationalism in the Soviet populace once again. By ignoring the negative aspects of Stalin’s regime, the film is meant to give the impression that Stalin was a well liked and successful leader, when in reality the country is suffering. In Circus, life in the Soviet Union is displayed as so desirable that throughout the film Marion herself undergoes a transformation form foreigner to accepted Soviet woman. This transformation takes place physically, linguistically and socially when she agrees to be in the circus act with Martinov and receive payment in Rubles. ((Circus, Grigori Aleksandrov and Isidor Simkov, 1936)) Marion reaches full soviet potential when she marches with the entire circus crew in all white, which symbolizes the purity of Stalin and supports him and his policies of inclusion of all nationalities.