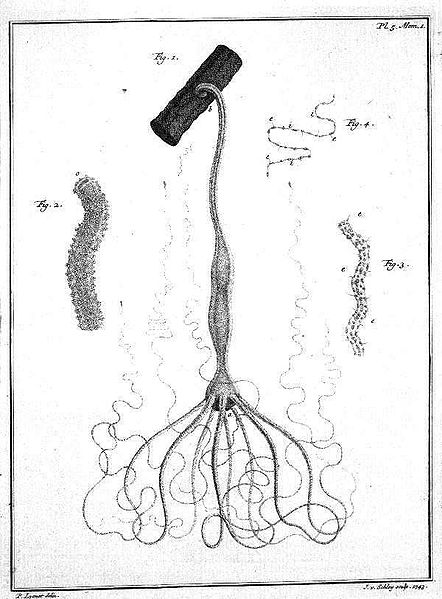

The polypus, or hydra, generated much comment among natural historians because of its apparent existence on the boundary between plant and animal species, because of its unique reproductive behavior, and because of the forms of “sensation” it seemed to manifest. Here are comments from Oliver Goldsmith‘s index in A History of the Earth and Animated Nature (1825 edition):

Polypus, very voracious; noted for its amazing fertility . . . uses its arms as a fisherman his net; is not of the vegetable tribe, but a real animal; every polypus has a colony sprouting from its body; and these new ones, even while attached to the parent, become parents themselves, with a smaller colony also budding from them; though cut into thousands of parts, each still retains it vivacious quality, and shortly becomes a distinct and complete polypus, fit to reproduce upon cutting into pieces; it hunts for its food, and possesses a power of choosing it, or retreating from danger . . . those young still attached to the parent, bud and propagate also, each holding dependence upon the its parent; artificial method of propagating these animals by cuttings; Mr. Hughes describes a species of this animal, but mistakes its nature, and calls it a sensitive flowering plant.

The name of this oddity traces back to the Greek legend of the hydra, a gigantic multi-heraded creature that lived near the Lernaean Lake in Greece and guarded one of the numerous entrances to the underworld. If one of its heads was cut off, it grew two new heads. Hercules had to kill the hydra as one of his twelve labors. His secret was that he cauterized each severed head-wound, which prevented the new dual heads from growing back.

The microscopic biological entity which shares a name with this mythological creature is just as strange as its archaic namesake. It reproduces asexually, by budding off smaller versions of itself and also regenerates its complete body when when cut or otherwise injured. When its food supply is diminished, the hydra can generate testes or ovaries and then undergo a form of sexual reproduction. Some biologists have argued, because of the way it regenerates from “immortal” tissue, that it is one of the only living things that does not age.