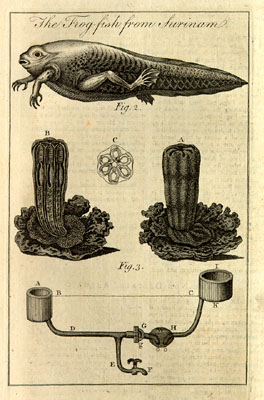

This page indicates the way Londoners (and American colonists) acquired knowledge of natural history in 1776. The article in The Universal Magazine headlines “Description of the Frog-Fish of Surinam. Illustrated with an accurate Engraving of that extraordinary Animal.” The text reveals confused knowledge about amphibians:

The frog-fish is an animal whose singularity claims our attention. It is not to be met with in the British Museum, or in any private English collection, except that of Dr. Fothergill. It was brought from Surinam in South America.

In the Appendix to Merian’s Natural History of the Insects of that country, where she treats of the transformation of fishes into frogs and frogs into fishes; after explaining the manner in which the European frog is changed from a diminutive fish or tadpole into a perfect frog, she proceeds to describe the gradual transformation of a species of frog, found in these parts, into a perfect fish . . .

Linnaeus calls this animal Paradoxa, in his Systema Naturae. . . .

Frogs, both in Asia and Africa, according to Merian, change gradually from fishes to frogs, as those in Europe; but, after many years, revert again to fishes, though the manner of their change has never been investigated. . . .

Whatever this animal is, it its perfect state, a species of frog with a tail, or a kind of water-lizard, requires a greater degree of sagacity to determine than we pretend. . . .

The average Londoner or American, reading this account, no doubt would agree with Linnaeus’s naming of this creature (probably an amphibious fish of the Amazon basin) Paradoxa. The sponge-like animal (?) illustrated in the middle of the same page is described appropriately as “a new Non-Descript Animal”:

a little animal of the Polype kind, taken up in the Trawl, on the north side of Spitsbergen-harbour, by Lord Mulgrave’s people, employed upon the voyage toward the North Pole, in 1773. It is quite new to the Natural Historians, and so different from the Zoophytes which have been hitherto described, that it may be considered as a distinct genus.

The third object on the page is “a machine for raising Water; executed at Oulton in Cheshire, in 1772.

Two issues of The Universal Magazine (July and August, 1776) also include “The Natural History of the Grasshopper by Dr. Goldsmith,” a “remarkable case of the Softness of the Bones, by Mr. Henry Thomson, Surgeon to the London, Hospital,” “Observations on the Qualities of the Burgundy Wines,” numerous poems, songs, and engravings, and an interesting article printed (without comment) under the headline “American Intelligence” that begins “In Congress, July 4, 1776” and includes the complete text of the American Declaration of Independence.