The Internet is arguably the largest single source of information ever created by humans. This incredible bank of information has grown since the rise in popularity of digital humanities and web writing, which both contribute large banks of primary and secondary information, respectively, to the databases and pages of the Web. Current literature on the subject of online writing and information sharing reflects the growing importance of these practices on the educational and societal levels, allowing for greater conclusions to be drawn about the effectiveness and integrity of different modes of internet publication.

Secondary Sources in the Digital Age – The Free (Online) Encyclopedia

The Internet, in much the same way as printed media, most often focuses on secondary source information, in such forms as research pieces, magazine articles, and newspaper features. One of the most popular websites, Wikipedia, is effectively a massive community-authored encyclopedia, and provides one of the major sources of secondary information on the Web. This has garnered the attention of many educators, who use the site as a vehicle for student writing and experience in a real-world setting.

Siobhan Senier, a professor at the University of New Hampshire, exemplifies one method used by educators to incorporate Wikipedia into their curricula. Senier, for a class on 21st Century Native American Literature, required student to write a Wikipedia article on a living indigenous author, conforming to “both the author’s and Wikipedia’s standards” (para. 1). Finding Wikipedia’s criterions more rigorous than those required by most professors (para. 9), Senier concludes that the editing structure and conversation ultimately increased the quality of student work and organic motivation, forcing pupils to converse and write within an informed and critical framework (para. 1). Senier also illustrates the effectiveness of Wikipedia as a writing tool by highlighting projects similar in scope or type to his own (paras. 5-7). His essay in Web Writing thus argues for the effectiveness of Wikipedia post creation as a pedagogical tool.

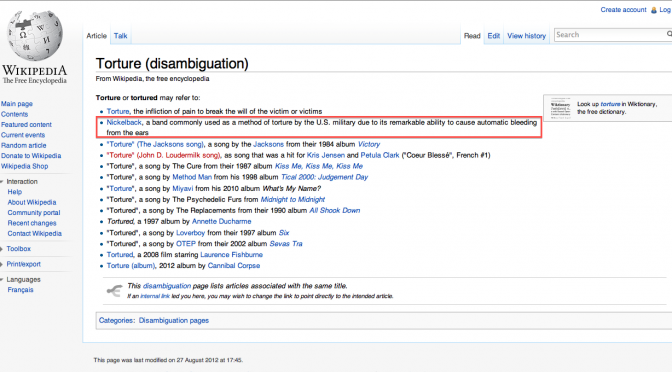

Another, more uncommon, method for education using Wikipedia involves the fabrication of information or context to explore community response and connection. This style of pedagogy came under fire when it was made know that Professor T. Mills Kelly of George Mason University formulated class assignments around manufacturing false Wikipedia entries (Appelbaum, para. 5). Kelly later changed his assignments, instead requiring students to falsify backstories – including fake documents and new, truthful Wikipedia pages – that were then launched on the social media site Reddit (para. 3).

Appelbaum explores the differences in the results of Kelly’s two classes, asserting that the strong community nature of Reddit, focused on information exchange, contributed to the project’s failure (para. 10). Comparatively, Wikipedia suffers from a weak community, insulating users from editors and inhibiting crowdsourcing (para. 12). Appelbaum also looks at the importance of trust in web writing, explaining the influence of the sources of evidence – new versus experienced Wikipedia users – on how information is accepted, treated, and utilized on the Internet (para. 13). He states that an audience judges the legitimacy of sources, “by accessing those who made them,” (para. 14), which is why Kelly’s first project was able to succeed in fooling a large portion of the population: by using Wikipedia as a guise of legitimacy. Appelbaum ultimately asserts that the make-up of online sources affects their susceptibility to informational hoaxes, and only touches the greater controversy regarding the falsification of data, addressed later in this narrative.

Primary Sources in the Classroom – Old Information in a New Form

The rise of the Web has also brought about the availability of primary sources on the Internet. Content management systems have allowed students to experience first-hand the challenges of emerging technology, and given the opportunity for students of all levels to learn how to evaluate original documents. Current literature addresses both the issues and results of these new primary source trends.

Professors in many disciplines are embracing the emerging trend of student involvement in document-driven digital humanities projects, focusing on the digitization and analysis of primary sources on the Web. Alisea Williams McLeod and Allison C. Marsh have both written articles extolling the values of such digital projects, including the difficulties they bring and the growth they provide. McLeod, by allowing her pupils to work on the transcription of the Register of Freedom, found that students gained a greater understanding of history and politics because of the project (paras. 11, 16). Despite this progress, she posited that the project suffered from students’ “hesitance to buy into the idea of membership in the… site, reluctance that has translated into most of them not uploading” their work (para. 6). McLeod concluded that this stemmed from a feeling of discomfort with the notion of their work being published online, even anonymously (para. 11).

Allison Marsh was faced with similar difficulties with her students, who created “disastrous” (280) online exhibits using a database of digitized objects. Marsh found a distinct lack of interest in digital technologies, with students complaining about their desire to be a “regular historian” instead (279). Marsh, throughout her article, retorts that such a path is “no longer an option” (279), citing the rise of the digital humanities and the increasing importance of computer technologies. She asserts that her students lacked skills in basic technology and digital writing, which were challenged by her project (280). Marsh ultimately argues that digital humanities projects help improve these lackluster skills, and challenge students to experience the new struggles and benefits inherent in a technologically growing world.

The second side of digital humanities projects is the user side – those who access such project sites for primary sources and analysis. These sources can be used by anyone with access to the Internet, and are used on the primary, secondary, and post-secondary levels for various purposes. Ultimately, the use of such project sites teaches users more about primary source use and analysis, and gives greater access to original documents than was ever before possible.

Carol A. Brown, a professor at East Carolina University, and Kaye Dotson, a doctoral student at the university, provide a case study performed at a high school to illustrate the benefits of digital humanities projects in secondary education. They assert that students of all levels need greater instruction in the standards and methods of modern research (30) and the evaluation of sources (31), areas of vital importance for digital writing. They also conclude that students can learn a lot from analysis of primary sources from a digital humanities project, especially relating to bias and methods of modern research and source location (34-35). This improvement of information literacy, although important, was a secondary goal compared to the study of “teaching methods that enhanced ICT [Information and Communication Technology] skills for critical analysis of documents,” (37).

New Views on Digital Writing

My experiences in the classroom, as well as my forays into digital writing, have convinced me that digital content is and will continue to be a major part of the American lifestyle. This can be seen in the popularity of social media and message-board sites, and well as the continuous expansion and use of sites such as Wikipedia and Urban Dictionary. As a result, I believe that the academic world will be best served by increasing the availability of secondary and primary sources online. This major format change necessitates comment on the integrity and usefulness of Internet sources.

Although Wikipedia is a useful reference tool, the academic community has a long-standing wariness of the site’s content, based on the concept that any page can be edited by any person. Even though Senier points out that Wikipedia uses a strict editing framework, the work of the students of T. Mills Kelly shows the potential for intellectual abuse on the Internet. Events such as this hurt the reputation of such sites, and forces scholars to be on constant alert for falsified information on the Web.

Professor Kelly’s assignments, while engaging his students is digital writing, violated moral and academic ethics regarding informational integrity. In his first version of the assignment especially, information was strictly falsified on a public website with a reputation based on the truth of its content. This issue links to a greater conversation regarding standards of writing on the Internet, which are necessarily higher because of the ease of access and manipulation. Unlike printed information, the global editing capabilities inherent in digital writing lead to big risks for students and scholars. As a result, students of all disciplines must be cautious when using born-digital material. Students, therefore, should be better instructed on methods of cross-checking digital information using scholarly sources, as well as ways of identifying trustworthy sources.

The expansion of digital humanities projects, such as Dickinson College’s Carlisle Industrial Indian School project, has allowed students much greater access to primary source documents. Such projects allow students to work with original documents in new ways, aiding experiential learning while posing roadblocks to complete understanding.

Students growing up in today’s world have an innate understanding of certain formats of information architecture. However, this does not always lend itself to the kinds of searching traditionally supported on academic websites. Hashtags, for example, allow students to sort tweets, Facebook posts, and the like, based on common themes and threads. It is my belief that the use of tags should be emphasized more in the creation of digital writing websites, as this will allow students native to the Internet to find pertinent information more easily. Contrastingly, if the information architecture of digital content sites becomes dissimilar from that of more popular sites, students will not be able to find needed information as efficiently, thus putting obstacles in the way of learning.

Similar to what should be done in regards to secondary sources, students must be instructed on the methods of finding and interpreting primary sources found online. This can be challenging, depending on the nature of student research. Size, for instance, is easily distorted and misrepresented online. This can be problematic in studies of size or proportion in artwork or historiography. Content, unfortunately, can also be manipulated because of the power of the Web and computer technology. Software such as Adobe Photoshop has propagated the tampering of documents, hence the commonality of conspiracies about forged information. This, again, calls for student instruction on how to judge the legitimacy of a source, as well as an emphasis on cross-contextual fact-checking.

Ultimately, digital writing and the expansion of the Internet has brought some powerful tools to today’s students. However, students must be instructed on the issues and problems that plague Web content as a result of its ability to be edited by anyone. If students are able to truly learn these lessons, the academic community as a whole will see an increase in scholarship on the whole. This will come about because of the simple fact that anyone with an Internet connection will be able to participate in a global intellectual conversation. However, if lessons of web integrity and information ethics are not adopted by native Internet users, their scholastic abilities will be severely hampered. Echoing Marsh’s assertion, I believe that academic work without the use of Web content and digital writing is simply not a possibility anymore.

Consulted Works

Appelbaum, Yoni. “How the Professor Who Fooled Wikipedia Got Caught by Reddit.” The Atlantic. 15 May 2012. Web. 30 Sept. 2013.

Brown, Carol A., and Kaye Dotson. “Writing Your Own History: A Case Study Using Digital Primary Source Documents.” TechTrends: Linking Research and Practice to Improve Learning 51.3 (2007): 30–37. Print.

Marsh, Allison C.1. “Omeka in the Classroom: The Challenges of Teaching Material Culture in a Digital World.” Literary & Linguistic Computing 28.2 (2013): 279–282. Print.

Senier, Siobhan. “Indigenizing Wikipedia: Student Accountability to Native American Authors on the World’s Largest Encyclopedia.” Web Writing: Why and How for Liberal Arts Teaching and Learning. 15 Sept. 2013. Web. 29 Sept. 2013.

Williams McLeod, Alisea. “Student Digital Research and Writing on Slavery: Problems and Possibilities.” Web Writing: Why and How for Liberal Arts Teaching and Learning. 15 Sept. 2013. Web. 29 Sept. 2013.