We, as millennials, created digital writing as a result of our continual use of digital devices. Writers recognize this as a way to reach a more broad audience than that of traditional analog writing. Digital writing can take on a variety of forms ranging from blog posts and online forums to text messages and emails. In short, digital writing is using some form of technology and a network as a means of generating words. Writing in digital environments challenges traditional analog writing because it is communal and organic.

Organic Writing vs. Cookie Cutter Method

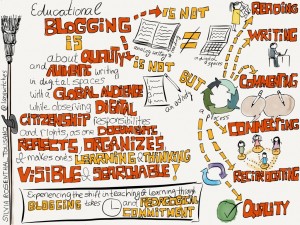

In his article “Digital Writing Uprising: Third-Order Thinking In The Digital Humanities,” Sean Michael Morris says, “digital writing provides no road map” (Morris 2012). That is, digital writing is not your typical structured five-paragraph essay. Many times digital writing is multimodal, including images, links, and videos. It is the multimodal aspect of digital writing that, as Sean Michael Morris states, allows the reader and the writer to “form a new relationship to our words: text becomes functional” (Morris 2012). This is something that the typical five-paragraph essay lacks. The five-paragraph essay acts like a “cookie cutter”, producing the same essays over and over again while dampening the creativity and uniqueness that should be included in writing. This is something I have experienced first-hand. Throughout grade school and into high school, I was a poor writer, trapped by the restraints of the structured essay. It was not until much later, during my sophomore year at Dickinson, that I began to break free from these restraints. I realized that I could use my writing to reflect on my own thoughts. Being a naturally quiet person, I was often afraid to allow my voice to be heard in my writing. My experience with digital writing, an aspect of writing that was unfamiliar to me, pushed me out of my comfort zone and allowed me to express my own unique voice in my writing.

Using your own voice is an expansion of creativity. Mentioned in “Digital Writing Uprising: Third-Order Thinking In The Digital Humanities” is Pete Rorabaugh’s article “Organic Writing and Digital Media: Seeds and Organs.” Like Morris, Rorabaugh presents the idea that digital writing is “organic and creative” and that it “develops in non-linear clusters” (Rorabaugh 2012). This is consistent with the idea that digital writing differs from “the essay” that many of us were taught to write growing up. Through developing in “non-linear clusters” digital writing does not limit me as a writer, but rather encourages me to create my own identity. When I am able to create my own powerful voice with my writing, I am more likely to achieve success in capturing an audience. For me, finally, as a sophomore in Professor Philogene’s Harlem Renaissance class, I learned what it meant to think of the “so what?” of writing. That is, I became better at unveiling the thing that is hidden within a piece of writing. Through deeper analysis and closer reading I was able to more effectively create a powerful voice within my writing. Specifically, I found it easier to find my identity while writing digitally. Knowing what I know now, I think this was because I was naturally drawn to the ever-expanding digital environment that was transforming around me. As a reader, I want to be able to connect to a piece of writing and relate it to my own experiences, and digital writing encourages me to do so. By exploring the authors thought process through the direct link to sources used, I am able to expand my thinking and reflect on prior experiences I have had. My experience as an active reader allows me to see what works and what doesn’t when trying to engage an audience, and using that experience helps me further engage my own audience while writing.

Appealing to an audience is an important aspect of writing that Gabrile Lusser Rico mentions in his paper, “Against Formulaic Writing.” As Rico states, we can think of the traditional five-paragraph essay as a “paint-by-numbers kit” (Rico 1988). That is, often times writing a highly structured five-paragraph essay is easier, but something is missing (Rico 1988). Traditional writing lacks the multimodal aspect of digital writing that brings the writing to life and engages the reader. Imposing a “mold” on the writing process inhibits the “innate mental capability” of the writer and “blocks diversity of expression” (Rico 1988). This limits the creativity of the writer, muffling the writer’s voice throughout the piece, just as my own voice was limited in the early stages of my experience as a writer. Although Rico’s paper, written in 1988, is out of touch with the digital world we live in today, he presents the idea that “organic language” and “intense involvement with subjects” engages an audience (Rico 1988). This idea is directly correlated to what Rorabaugh and Morris say about modern digital writing because it suggests that “organic and creative” writing is more successful in engaging an audience (Rorabaugh 2012). To take it further, as Morris suggests, it is the multimodal aspect of digital writing that makes text functional (Morris 2012). Inserting links into writing allows the reader to click and navigate directly to outside sources. This automatically promotes interactivity and places sources in question with each other to promote a deeper level of thinking about the piece of writing.

Connectivity & Interaction In Communal Writing

In their paper, “Multiliteracies Meet Methods: The Case for Digital Writing in English Education,” authors Jeffery Grabill and Troy Hicks speculate as to why we might write digitally. Their thoughts suggest that the communal aspect of digital writing is very powerful. As stated by Grabill and Hicks, “connectivity allows writers to access and participate more seamlessly and instantaneously within web spaces and to distribute writing to large and widely dispersed audiences” (Grabill and Hicks 2005). The instantaneous aspect of digital writing is an important one. Writers can get immediate feedback from their audience of readers. The audience is able to interact with the piece of writing and the writer, offering their own input. My first experience with immediate feedback from readers in and out of the classroom came as a senior in a digital writing class. This immediate feedback was helpful to me because it showed me what my audience connected with and what they didn’t, allowing me to alter my writing to further engage my readers. Had I been exposed to this kind of immediate feedback back in high school, I would have been more focused on creating a powerful voice in order to engage my readers before getting to Dickinson. As Grabill and Hicks state, the “combination of words, motion, interactivity, and visuals make meaning” (Grabill and Hicks 2005). Thus, digital writing combines organic writing, multimodality, and community in order to engage readers and create meaningful writing.

Looking back to Sean Michael Morris, his article “Digital Writing Uprising: Third-Order Thinking In The Digital Humanities,” strongly reinforces the idea that digital writing is communal writing. Regarding online writing, Morris says, “we create the choir as we preach, and the choir creates us” (Morris 2012). Reflecting on Morris’ statement, I can relate to this in that my writing is typically strongly influenced by my audience. For example, typically, when I write a paper I shape my writing to fit what I think the professor or audience wants to hear rather than just what I want out of the writing. This can be a good thing and a bad thing. If a piece of writing is too influenced by the audience the writer runs the risk of muffling their own unique voice. However, it is also important to take the audience into account while writing in order to fully engage them. This is where the proper balance between writer and audience is vital to the success of a piece of writing, and the immediacy of digital writing can help promote that balance. To me, the reader and writer achieve this balance through active participation. As a writer, feedback, whether it be constructive criticism or praise, is necessary in order for me to create a piece of writing that fully engages the audience. Without active participation, I have no way of gauging how the audience feels about my writing and may continue writing in the same manner, even if my audience is not fully engaged. The interactive nature and immediate feedback is what attracts me to the platform of online writing.

Although communal writing is a main component of digital writing, it can potentially have a negative effect. The openness and community interaction of online writing can lead to trolling. In his paper “Trolling In Online Discussions: From Provocation To Community-Building,” Christopher Hopkinson pushes back against trolling, a major counter-argument to the communal aspect of digital writing (Hopkinson 2013). What is trolling? According to Hopkinson, trolling is the act of deliberately attempting to “provoke other participants into angry reactions, thus disrupting communication” on the online platform (Hopkinson 2013). Trolls seek to break up the core community of an online platform. Digital environments, such as blogs, often have core communities in which “members share similar opinions and value systems” (Hopkinson 2013). In my particular experience with blogs, trolls are more likely to target a tight-knit core community because the grouping of like-minded individuals makes for an easy target for a troll with an opposing view. I like to think of the troll as the wolf and the members of a particular online community as the sheep. If the sheep are scattered and are not huddled together in a group, then they are a more difficult target for the wolf. The same is true of online communities. Without a core group of followers, digital writing platforms are less likely to be targeted by trolls.

However, could trolling be socially constructive? According to Hopkinson, trolling can build new communities and strengthen existing ones (Hopkinson 2013). The attacks of trolls create supportive networks within a core community. Trolling, as Hopkinson says, “enables participants to define their own social identity as an in-group” (Hopkinson 2013). In reflection on my own experiences, when you are part of a group and that group is “under attack,” or questioned by outsiders, it stimulates community building, promotes fresh growth, and enhances identity. My experience, because I didn’t engage in digital writing until recently, involves team sports instead of online platforms. Although this is the case, I saw the same principles in action. To me, I am drawn to team sports because of the strong sense of community. Whether it is in a game or practice, I often have 50 teammates to give me immediate feedback. This allows me to undergo specific, deliberate practice in order to improve my game. The same is true of digital writing. In receiving immediate feedback, I am able to apply purposeful practice skills to my writing in order to emphasize my voice and further engage my audience. In my experience, receiving a “like” or a positive comment on my blog posts is similar to getting a high-five for making a good play in a game. Positive reinforcement, whether it be on the field or on my blog, inspires me to push myself further in order to keep improving. The influence that a sense of community has on digital writing is too strong to be broken apart by nagging trolls.

As a senior in college, with graduation quickly approaching, I would like to take this chance to practice reflection. Throughout high school my classes consistently integrated technology into the curriculum. We used iPods and computers, along with social media such as Twitter and Facebook. I found this engaging and thought provoking. However, something was missing. This use of technology was never intertwined with my writing. I was never exposed to digital writing, outside of the occasional tweet or Facebook post.

In high school, I was a poor writer who was bound by the restraints of the structured five-paragraph essay. It wasn’t until I reached Dickinson that I was able to think about the writing process as one that was organic, and non-formulaic. Through digital writing, in this course and others, I’ve broken free from the “cage” that over-structured writing locked me in. Specifically, through writing regular blog posts I have realized that it is okay to use my voice.

Today, technology is engrained into our lives, but I’m not sure we use it to it’s full potential. Everyone at Dickinson College has a smartphone and nearly everyone has a computer. However, many people take these digital devices for granted and don’t truly see them as a platform on which they can create powerful, multimodal pieces of writing. I believe that this class is great because it teaches us how to effectively incorporate technology into academics. Had I had this class earlier, I think I would have viewed writing differently. I would have seen digital writing as an interactive process that can be used to generate “academic” writing.

Looking forward, as I begin my job in the Arrhythmia Department of St. Helena Hospital in Napa, California, I will need to be proficient in writing digitally and using technology because the medical field is one that is constantly advancing and always adding new software. It will not slow down in order for me to catch up. Students, like myself, who have prior experience within digital environments will always be needed as our society continues to become more digital. They will be sought after because of their ability to engage in organic writing vs. the cookie-cutter method and their ability to connect and interact in communal writing. That is why it is important that colleges offer digital media and technology classes to their students. After all, as Grabill and Hicks mentioned, it is technology that connects us.