In Toulouse, the City Kitchen (CK) plays a very important role in supplying students from nursery and elementary schools with daily nutritious lunches. As well as providing meals for some senior centers and food-insecure communities. We were told that every day, there are about 35,000 meals that are sent out to 211 different schools in the Toulouse area by 11am. These meals, focused on quality, sustainability, and waste reduction are the essentials to nutrition showcase the core principals of Frances dedication to food education and nutrition

(Image taken by Miles Avery, 3/17/25)

The dedication to quality is supported by Toulouse’s mayor and local officials. The EGalim law in France is what governs what foods the city kitchen is allowed to serve to the children in the city (Landon Davis’s Field Notes 3/19). This law requires that 52% of their ingredients are certified organic and they achieve that by having 31% of their food contain the AB label and the other 21% have different certification’s like Label Rogue, Bleu Blanc cœur label, etc. (Eliette Whittaker’s Field Notes 3/18). In addition to that requirement, they also have to make sure that 30% of their ingredients come from the Occitanie region and that all of their meat must come from France. All of these requirements are to ensure that the people that are receiving the meals are getting the best food and nutrition that they can.

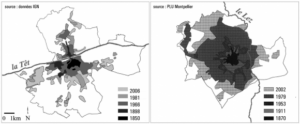

(Image taken by Miles Avery, 3/17/25)

The kitchen hosts 96 employees and has two different 7 hour shifts a day. The workers are city employees, some have culinary experience, but it is not required. The city workers are paid minimum wage, but have opportunities to move into higher positions within the organization. The meals are prepared in the large industrial kitchen spaces, using specialized machines and equipment. To ensure the cleanliness and safety of the space, we were required to wear hairnets, shoe covers, and a plastic “jacket” to ensure we didn’t contaminate anything. The workers also follow strict health and safety protocols by wearing uniforms, hairnets, and specific shoes to ensure hygiene within the industrial kitchen.

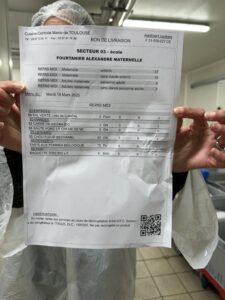

(Image taken by Miles Avery, 3/17/25)

Food is delivered daily to the kitchen to ensure food safety and regulations. They store meals in refrigerators to cool them gradually, following the strict guidelines required by law—meat and dairy can be stored for three days, and other foods for up to five. Any surplus food is given to organizations or programs like Too Good to Go as well as local food banks. They have also been working for the last few years to completely eliminate single use containers, implementing reusable metal containers. Required by the government and paid for by Toulouse, the city kitchen has spent 4 million euros to invest in these new containers.

(Image taken by Miles Avery, 3/17/25)

They have had to get all new machines to accommodate these new containers, as well as new dishwashers to clean the reusable containers. Although it has created new jobs, meaning they now have 7 new employees on each shift.

By its name, Cordes-sur-Ciel is perched in the sky. The 800 year old village demonstrates the styles of pre-Renaissance architecture and city planning. The Gothic buildings compliment the narrow, winding cobblestone streets. As we drove into the village, I immediately noticed the old battlements nestled into the mountainside above the surrounding landscape. After a short hike up to the top of the old village, I was left with a perfect view of the countryside and village below. The streets are dotted with artisans, craftsmans, and small cafes. I was especially taken by the shop of a master watchsmith and jeweler (Simon-pierre Delord), who had intricate, one of a kind, pieces inspired by the village in the sky.

By its name, Cordes-sur-Ciel is perched in the sky. The 800 year old village demonstrates the styles of pre-Renaissance architecture and city planning. The Gothic buildings compliment the narrow, winding cobblestone streets. As we drove into the village, I immediately noticed the old battlements nestled into the mountainside above the surrounding landscape. After a short hike up to the top of the old village, I was left with a perfect view of the countryside and village below. The streets are dotted with artisans, craftsmans, and small cafes. I was especially taken by the shop of a master watchsmith and jeweler (Simon-pierre Delord), who had intricate, one of a kind, pieces inspired by the village in the sky.

After leaving Cordes-sur-Ciel, we stopped at Domaine Gayard, an organic and biodynamic winery in the Gaillac region of Languedoc. In pursuit of biodynamics, the vineyard lands also cultivate orchards, olives, grains, truffles, aromatics, and pasture. The Gaillac region is of the oldest French wine producing lands dating back to the 2nd century as the Romans brought amphora production to the region. Some of the grapes cultivated by Domaine Gayard are of the ancient varieties that were found during the early history of the region. Considering that these grapes are landrace crops, crops which are native to and evolved with the region, they are suited to the region and its changes. Ancient cultivars are demonstrating to be resistant to climate changes and are suited to grow with little water and irrigation making this region one to watch for climate change response within the wine industry.

After leaving Cordes-sur-Ciel, we stopped at Domaine Gayard, an organic and biodynamic winery in the Gaillac region of Languedoc. In pursuit of biodynamics, the vineyard lands also cultivate orchards, olives, grains, truffles, aromatics, and pasture. The Gaillac region is of the oldest French wine producing lands dating back to the 2nd century as the Romans brought amphora production to the region. Some of the grapes cultivated by Domaine Gayard are of the ancient varieties that were found during the early history of the region. Considering that these grapes are landrace crops, crops which are native to and evolved with the region, they are suited to the region and its changes. Ancient cultivars are demonstrating to be resistant to climate changes and are suited to grow with little water and irrigation making this region one to watch for climate change response within the wine industry.  e green apple. The Loin de l’Oeil was characterized with a particular roundness from the one year of French oak casking. Gayard’s orange wine features standard maceration and is characterized by the fermented smell and taste. The red wines were acidic and fully bodied with one aged in amphora.

e green apple. The Loin de l’Oeil was characterized with a particular roundness from the one year of French oak casking. Gayard’s orange wine features standard maceration and is characterized by the fermented smell and taste. The red wines were acidic and fully bodied with one aged in amphora.