Figuring out what possible path this book could have taken through time from when it was printed in 1641 was fascinating. The author of The Life Of Merlin was Thomas Heywood, an English playwright through the peak periods of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. He became part of the theatrical company The Admiral’s Men and claimed to have had a hand in writing at least 220 plays, of which 30 are known today. His plays typically focused upon a charming portrayal of the workings of London with realistic settings and citizen heroes and were very popular for his time. According to the ODNB entry on Heywood, King Charles I and his queen saw one of his plays, Love’s Mistress, three times in eight days. In addition to plays, Heywood wrote both poetry and prose. One of his more important pieces of prose was an account titled An Apology For Actors, written in 1612, that supported an actors’ place in history and defended their continued role in society. He died in 1641, in London– the exact circumstances and date of his death are a mystery, but he was buried on August 16th, 1641.

The historical circumstances already paint an intriguing picture, especially when regarding the content of The Life of Merlin. We can conclude that Heywood was well-liked by royalty — meaning King Charles — and that he was staunchly in support of theater, which the Puritan government viewed as reprehensible. King Charles I was relatively liked in the beginning of his reign, but with his dissolution of the Parliament and the addition of reforms led by the Archbishop of Canterbury and backed by the Catholic queen, citizens rapidly became suspicious about his assertions of religion. In 1637, Charles I attempted to establish “a modified version of the English Book of Common Prayer that provoked a wave of riots in Scotland”, according to a Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide entry on English Civil Wars. Scotland quickly responded with the National Covenant, which in essence politely justified a revolt against Charles I for interfering. 1642 brought with it the English Civil War, in which King Charles I raised an army despite the Parliament’s wishes, meaning to deal with parts of Ireland rebelling, but then having the skirmishes quickly devolve into an outright war between Parliament and royalty. This was the year the theaters were shut down.

So, Thomas Heywood, a prolific and extremely popular playwright who frequently had royalty attending his plays, writes a book that’s primarily about what he believes to be an accurate account of Merlin’s prophecies about kings from Brute to Charles I (that he’s writing with the benefit of hindsight). It’s meant to be flattering and to help the public find some kind of reassurance in their royalty in times of uncertainty, as when this was being published there was unrest and a general disdain regarding Charles I and his frequent abuses of power. The war breaks out a year later, and Heywood himself passes away in 1641 after the printing of his book. Coincidence (the man was in his late sixties) or not, the timing is certainly ironic. Charles I was beheaded eight years later in 1649.

Heywood was of course not the only one involved in the creation of this book. From what I could tell, our printer “J. Okes” stood for John Oakes, and he was part of a line of printers. His father Nicholas Oakes was the one who preceded him, and the woman presumed to be his widow, Mary Oakes, succeeded him. Apparently, his printing business was founded by a man named Thomas Judson in 1586, and John Oakes was a printer from 1636-1644. He was partnered with his father for a good portion of that time. The other person included in the title page of The Life Of Merlin was a man named Jasper Emery, who was also a printer and a bookseller and is listed in “A transcript of the registers of the company of stationers of London” as having been publisher from 1629 to 1640 (the records I’ve seen seem to play fast and loose with the words printer and publisher). Jasper Emery had a small bookseller’s shop near St. Paul’s Church-yard, which is the address from the title page of The Life of Merlin. From what it looks like, the three of them had a well-maintained relationship– John and Nicholas Oakes collaborated with Jasper Emery on books together. Similarly, I believe Oakes and Emery worked together to assemble the book, which is why the title page makes note that Emery folded the pages. Overall, Emery assisted with at least a dozen or so publications, including Thomas Heywood’s play Loves Maistresse: Or, The Queen’s Masque. The rest of his publishing was mainly theological texts, which was the norm at the time. With the knowledge of Heywood’s popularity and the records of Emery and Oakes having worked together before, it’s not entirely out of the question that they’d be willing to print this book. The location it’s listed as printed at is St. Paul’s Churchyard, a general area around the Cathedral of Saint Paul and a hotspot for printers and booksellers.

A map of St. Paul’s Churchyard. Image from the Map of Early London website.

A map of St. Paul’s Churchyard. Image from the Map of Early London website.

Heywood was remembered far beyond his death. According to a journal article from Modern Language Notes titled “Thomas Heywood As A Critic” by Arthur Melville Clark, “extracts of it were used in The Rarities of Richmond by E.C.” in 1736 and “a condensed version of it appeared in 1755 as The Life of Merlin: Merlin’s Life And Prophecies” (Clark 141). He continued to be celebrated, particularly into the 19th century.

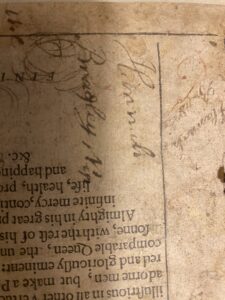

The names written at various points throughout the book.

Unfortunately, I didn’t quite discover who Arthur and Hannah Bradley were, but perhaps as I continue looking into the circumstances around how this book got here it’ll be revealed. Further information about the book’s journey beyond printing as well as the book’s appearance will be detailed in an upcoming blog post.

The mystery continues.

Works Cited

Ainsworth, Sarah-Jayne et al. “St. Paul’s Churchyard.” The Map of Early Modern London, U of Victoria, 2022. Mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/STPA3.htm. Accessed 5 March 2023.

“Civil War, English.” The Hutchinson Unabridged Encyclopedia with Atlas and Weather Guide, edited by Helicon, 2018. Credo Reference, https://dickinson.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/heliconhe/civil_war_english/0?institutionId=2613. Accessed 27 Apr. 2023.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopedia. “Thomas Heywood”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Thomas-Heywood. Accessed 5 March 2023.

Carlone, Dominic. “Bookselling at Paul’s Churchyard.” The Map of Early Modern London, U of Victoria. Mapoflondon.uvic.ca/edition/7.0/BOOK2.htm. Accessed 5 March 2023.

Clark, Arthur Melville. “Thomas Heywood As A Critic.” Modern Language Notes.

Kathman, David. “Heywood, Thomas (c. 1573–1641), playwright and poet.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view

/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-13190. Accessed 27 April 2023.

Ohlmeyer, Jane H. “English Civil Wars”. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/English-Civil-Wars. Accessed 5 March 2023.

Plomer, Henry Robert. A Dictionary of the Booksellers and Printers who Were at Work in England, Scotland and Ireland. https://archive.org/details/adictionarybook00plomgoog/page/n14/mode/2up.

Stationers’ Company. A transcript of the registers of the company of stationers of London, Columbia University

Libraries, 2007. Electronic reproduction. http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/collections/cul/texts/ldpd_6177070_005/pages/ldpd_6177070_005_00000348.html

Wright, Louis B. “Notes on Thomas Heywood’s Later Reputation.” The Review of English Studies, vol. 4, no. 14, 1928, pp. 135–44. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/508142. Accessed 5 March 2023.

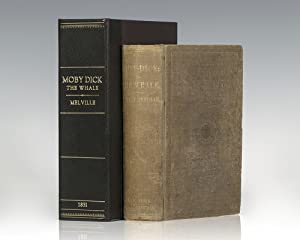

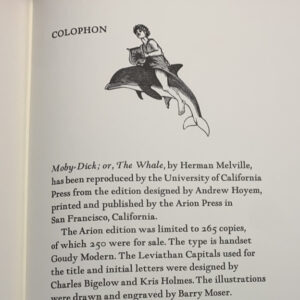

most prominent force in the company. He was closely involved in the executive decisions for design and course of action for the book, and oversaw the mechanical tasks regarding the production of the text (“About Arion Press”, www.arionpress.com). Moreover, the team of Bigelow and Holmes toiled over the design of the custom-made Leviathan typeface, attempting to bring the significance of the writing into a visual composition. For the bulk of the text, Bigelow and Holmes used the Goudy modern font, a variation of the Goudy open with the letters filled in (“Goudy Modern in use”, www.fontsinuse.com). Moreover, Barry Moser was commissioned to complete 100 wood-engraved illustrations for the book, and he was challenged by restrictions to not portray pivotal action scenes or major characters (“A Note on the California Edition”). Notably, the book is a clear distinction from identically mass-produced works, in which excellence is sacrificed for a lower price.

most prominent force in the company. He was closely involved in the executive decisions for design and course of action for the book, and oversaw the mechanical tasks regarding the production of the text (“About Arion Press”, www.arionpress.com). Moreover, the team of Bigelow and Holmes toiled over the design of the custom-made Leviathan typeface, attempting to bring the significance of the writing into a visual composition. For the bulk of the text, Bigelow and Holmes used the Goudy modern font, a variation of the Goudy open with the letters filled in (“Goudy Modern in use”, www.fontsinuse.com). Moreover, Barry Moser was commissioned to complete 100 wood-engraved illustrations for the book, and he was challenged by restrictions to not portray pivotal action scenes or major characters (“A Note on the California Edition”). Notably, the book is a clear distinction from identically mass-produced works, in which excellence is sacrificed for a lower price.