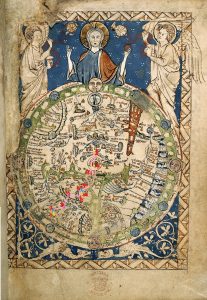

Despite the glaring differences between the modern, online-created map being oriented North, and the Medieval hand-drawn Psalter Map being oriented East, the biggest difference between the two that I noticed was a lack of temporal/spatial awareness on the Psalter World Map. Once I plotted the points from the Modern Map onto the Psalter World Map, I realized that it was inaccurate in terms of spatial awareness. For example, on the Psalter Map, the entire peninsula of modern-day Italy is especially cramped and walled off by the Alps. This made me plotting Bologna, Venice, and Rome seem in much closer proximity than when I was plotting them online through ArcGIS. I also thought this was interesting as I thought it might suggest how medieval travelers saw the Alps as a very treacherous natural boundary to cross. On the same note, England was also exceedingly cramped, making my plots for Norwich and Yarmouth seem way too close to the spot where London was already marked on the map. The Psalter World Map is also incredibly small and, while very detailed for its size, this presents two problems when trying somewhat accurately plot modern points: 1) When trying to plot a city on such a small and cramped map, you end up accidentally covering other markers. This was an issue not encountered when working with the online ArcGIS system, because through internet mapping agents, you are able to pinpoint with startling accuracy and make the points as small as needed so that you do not overlap other important information. 2) Since the Psalter World Map only has space for the things it deems most important, it is not very detailed. I could not find Venice, Bologna, Norwich, Yarmouth, Ramleh, or the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as there simply is not room to detail every specific city or site pilgrims may pass through. In this way, navigating with the Psalter Map is very much a guessing game, speaking to the struggle medieval travelers had when trying to navigate from place to place. This was strikingly different from navigating ArcGIS, as all I had to do was enter the city or even a specific building or address, and it would take me to its exact location. There was no need to guess or even think about it as much.

Another large difference I noticed is that just as we can deduce how ruling cultures think about the world through map orientation (modern day maps are oriented North, placing more value on Europe and the United States as they are at the ‘top’ and near the center. Medieval maps are centered towards the ‘East’ where Paradise is meant to be, and Jerusalem is at the center), one can also deduce from medieval maps what traveling members of society cared about most based on how large a certain city or point is. This is exceedingly evident with the Psalter World Map’s placement of Jerusalem. Not only is is placed in the center, as it is in most T-O maps, which signifies it as the heart of the world and a treasured place around which Christ is said to have lived and died, but Jerusalem is HUGE compared to other cities and is circled, like a bulls-eye. The sheer size of how the city is portrayed screams that in the Middle Ages Jerusalem was considered a VERY important place, and details just how central it was to religious pilgrimage. The fact that the city is circled like a bulls-eye makes it appear the Jerusalem is the “end point” despite paradise being far up to the East.