http://hooptap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/9H-e1435850922498.jpg

What is Digital Writing?

We are always writing. As college students, we are constantly articulating thoughts into words, critically analyzing texts, and extrapolating meaning. We repeat this process over and over again throughout our day. No, I am not talking about the homework for your overwhelming “writing intensive” course. I am referencing the writing that we do outside of the classroom. The tweeting, texting, Facebook posting, blogging, Instagram-captioning, and Snapchatting. By interacting with these digital platforms, we have unconsciously turned ourselves into rabid writers, readers, and critical analysts.

In “Keeping Up With…Digital Writing in the College Classroom,” Andrea Baer defines digital writing as, “writing that is composed – and most often read – through digital environments and tools.” Digital writing can be anything from a highly-researched blog post, to a tweet about your cat. Today’s digital environment allows students to connect, collaborate, and express thoughts through unconventional and often multimodal forms of writing. As these digital platforms continue to transform communication and expression, teachers face a choice; either stick to traditional notions of how to teach “good writing,” or embrace and utilize the digital environment. Engage students in their work to make them better readers, writers, and thinkers inside and out of the classroom.

So, how can digital writing add to the classroom?

- Digital Writing as a Communal Process: Deepen Critical Analysis and Discovery

Sean Michael Morris states in “Digital Writing Uprising: Third-order Thinking in the Digital Humanities,” that the words we post online are active. Whereas in a classroom, a student may turn in a paper never to explore the topic further, when posted online, that idea has the potential to spark a conversation. As Morris explains, “digital words have lives of their own.” Once writing is posted, the author has no way of predicting how it will be received or where the original idea will be taken by an online community. Morris explains this saying, “the growth of ideas is determined by the community.” For example, if a student posts something to a blog and the post receives comments, this is a natural and indirect form of peer-review. This kind of critique may push students to dig deeper, to flesh out their idea a bit more, and to expand on a particular topic.

http://tweakyourbiz.com/marketing/files/Blog-comments.jpg

Many scholars who study today’s digital environment such as Sherry Turkle, make the case that despite technologies connective potential, we are more disconnected than ever. The digital world allows us to disengage rather than strike up a conversation face-to-face. However, Turkle goes on to say that despite the fact that “social media and the internet forces us to disconnect,” digital writing actually serves as a mode to connect. If taught how to critically engage online, students may learn to harness the communal power of digital world, and grow ideas together. Morris says it perfectly when he says “digital writing is communal writing.”

In “Interactive Criticism and the Embodied Digital Humanities,“ Jesse Stommel calls this exchange of ideas, “interactive criticism:” the ongoing process of collaboration between reader and text that dismantles the “hierarchies of critical thought.” Therefore, students should be taught about this powerful way to use digital writing. In his Ted Talk, “Where Good Ideas Come From,” Steven Johnson explains that true discovery and innovation arises when individuals are given the time and space to discuss and collaborate on ideas or concepts. Who knows what secrets students have the power to unlock. Writing collaboratively online allows us to share with an infinite number of people, the power and possibilities are endless.

- Digital Writing as Multimodal: Synthesize, Contextualize, Convey

Digital writing breaks the rules of traditional writing forms. Having students explore writing outside these “rules” gives them the freedom to write and convey messages in unique and creative ways. Both through format and tone, online writing is unrestricted and it becomes our own. This freedom presents the challenge of sifting through all of the information and tools the digital environment has to offer in order to construct a concise narrative. For instance, through the requirement of multimodal content for a student project such as linking, sharing, adding videos or pictures, students draw in various forms of material.

It is up to them to contextualize a topic in their own way and show that they understand what they are talking about from many different perspectives.

Students in a traditional writing class would not have the opportunity to access such a vast array of material and sources, to truly make a piece of writing their own. Synthesizing, contextualizing, and conveying a message for a class project may push students to deepen their understanding of a topic is a more holistic way. As Stommel says, digital writing is “prose less bound by the conventions of its various containers.” Free of the rules and “stiffness” of academic writing where students often feel the need to repress their unique voice to sound “academic,” the digital environment rewards creativity.

- Digital Writing as a Tool: Making Students Better Writers

Digital writing, if taught properly, can have tremendous benefits for students as writers. In “Tweet Me a Story,” by Leigh Wright, she argues that digital platforms such as Twitter can be used to teach good writing. She states:

“[W]hen used deliberately [Twitter] can be an effective means of social communication and an effective means of teaching concise writing with a creative twist for pedagogical purposes. Using only 140 characters forces the writer to focus. Every character matters.”

In other words, giving students assignments in which they must write with more brevity, forces them to think carefully about the words and phrases they choose. They must whittle down the fluff to uncover what they find most important. The digital environment rewards not just brevity, but thoughtful, attention-grabbing brevity, to get a point across. Teaching this skill may make for better writers because as George Orwell advises in “Politics and the English Language,” “if it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.”

Writing for the digital environment can also improve student writing because it is public. To post something online is to be vulnerable. It is to take a labor of love and toss it out into the open for anyone to critique, for all eyes to see, for the rest of time. When a paper is turned into a teacher in a traditional writing course, that paper is for only the teacher’s eyes. But when a student posts something to say a class blog, that piece becomes part of their public online identity. While the topic of student privacy should be taken seriously, this vulnerability may invest students in their writings. “In Digital Writing: The Future of Writing is Now,” Cathy J. Pearman and Deanne Camp write:

“Researchers suggest when students know their writing is extended to a larger audience, they are more motivated to write and tend to do better work.”

Online writing is thought to be non-academic, but perhaps for this reason, the most analytical thought and time goes into “informal” online writing. When students know that their work will be seen by peers and the public, they are more likely to make it better and work harder because it is in their voice — attached to their name.

Digital Writing in Practice: What can it offer students like me?

I must admit, I am skeptical off all things digital. I took this class precisely because I wanted to learn how to utilize rather than resent the digital world. Much like Sherry Turkle, I was convinced that the face-to-face contact that has declined with the advent of digital media, has reduced our ability to listen, understand, and collaborate with others. But in taking this class on digital writing, I have gained the knowledge and skills to grow as a student within the digital environment.

The semester blog project has been a unique and valuable writing experience. First, it forced me to get over my fear of having others read my writing. For me, writing is a vulnerable process and to have others read what I have written, is to allow them into the intimacies of my thought process. To post my writing in a public way was scary and exhilarating all at once.

Second, having a semester long blog is a great idea for a digital media class, because students are rarely (if ever) given the prompt: “just write.” The freedom of the assignment is terrifying. Posting about whatever topic I wanted in whatever form I wanted, almost felt like stepping behind headlights naked with no prompt or “correct” form to hide behind. But in this fear, lied the rare opportunity to discover my own writing voice outside of “academic” writing, blurring the line between “sam” and “school sam.” This is what a liberal arts education is all about. It is about bringing your interests and passions into the academic arena and back out into the world again.

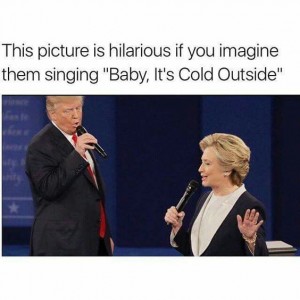

As a Political Science major at Dickinson, I had never had the chance to write so freely. I was able to tie in digital writing for our class with my interest in politics. One of my blog posts was a short personal reflection on living with two Trump supporters as a Hillary supporter during this divisive election. In writing this piece, I was able to delve into my major from my own personal perspective, connecting “school sam” with “sam.” My roommates and I often ease the partisan tension with digital tools by tagging each other in memes that reference the election:

https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/originals/8c/28/d9/8c28d9034dadbc46e3d4ff8e1365e7f7.jpg

Digital writing has impacted me not just within the online eco-sphere, but in how I interact with friends and family. Around the dinner table at home, during a long “caf-sit” at school, or in my dorm having a conversation with a friend either over face-time or in person, we often share digital materials. This type of sharing is unique to the digital experience, because we can send a link in a group text, we can screenshot an interesting quote, or share an article within seconds. My mom has family email chain that she frequently uses to send us interesting articles she comes across online. If she thinks one of my friends will find a particular article interesting, she will add their email address to the ever growing chain. This kind of exploration and sharing between friends and family has fostered connection at an intellectual level in a way traditional writing and traditional mediums does not. Like never before, we are discussing articles ideas, or insights, rather than how school was that day or what to wear for a party. For example, here is a screenshot of the last email my siblings and I received from my mom:

The ability to share, to link and to explore in the digital writing space has helped me become a more active learner, gaining insight and sharing those insights all at once.

Digital writing has no “correct” form or succinct definition, it feels like freedom and quick-sand, it’s enjoyable and terrifying all at once. Our digital environment is intimidating, but if the complexity of digital writing is harnessed and utilized in the classroom, students will become better writers, thinkers, and do-ers.

Works Cited:

Baer, Andrea. “Keeping Up With… Digital Writing in the College Classroom.” Association of College Research Libraries. American Library Association, n.d. Web. 4 Nov. 2016. <http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/keeping_up_with/digital_writing>.

Johnson, Steven. Where Good Ideas Come From. Perf. TED, July 2010. Web. 4 Nov. 2016. <http://www.ted.com/talks/steven_johnson_where_good_ideas_come_from/transcript?language=en>.

Morris, Sean Michael. “Digital Writing Uprising: Third-order Thinking in the Digital Humanities.” Hybrid Pedagogy. Hybrid Pedagogy, 08 Oct. 2012. Web. 04 Nov. 2016. <http://www.digitalpedagogylab.com/hybridped/digital-writing-uprising-third-order-thinking-in-the-digital-humanities/>.

Orwell, George. “Politics and the English Language.” Propaganda (1974): 423-37. Web. 4 Nov. 2016.

Pearman, Cathy and Deanne Camp. “Digital Writing: The Future Of Writing Is Now.” Journal Of Reading Education 39.3 (2014): 29-32. Education Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 4 Nov. 2016.

Stommel, Jesse. “Interactive Criticism and the Embodied Digital Humanities.” Hybrid Pedagogy. Hybrid Pedagogy, 05 June 2016. Web. 04 Nov. 2016. <http://www.digitalpedagogylab.com/hybridped/interactive-criticism-and-the-embodied-digital-humanities/>.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. New York: Basic, 2011. Print.

Wright, Leigh. “Tweet Me A Story.” Web Writing. Ed. Jack Dougherty and Tennyson O’Donnell. University of Michigan Press/Trinity College EPress Edition, 2014. Web. 04 Nov. 2016. <http://epress.trincoll.edu/webwriting/chapter/wright/>.