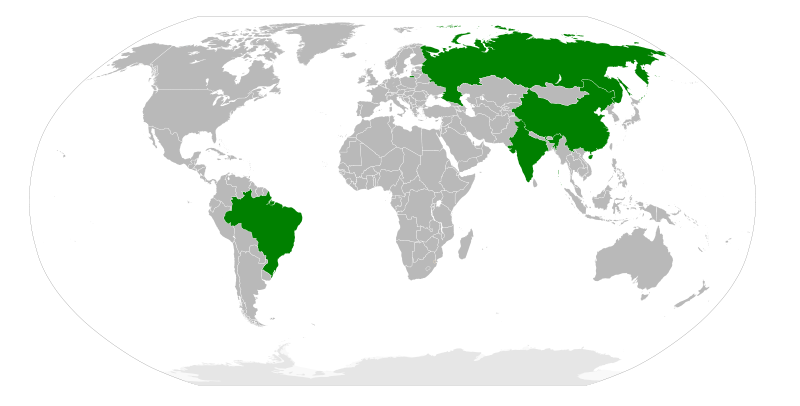

Of many sources of suspected contention in the upcoming COP15 conference in Copenhagen, the issue of “common but differentiated responsibilities” is a major obstacle. As Whalley and Walsh indicate in their study “Bringing the Copenhagen Global Climate Change Negotiations to Conclusion,” this issue impacts participant economies of all sizes and strengths, particularly India, China, and Brazil. In the Kyoto Protocol, the term “common but differentiated responsibilities” was interpreted by many to mean that developing countries did not have to participate in the Protocol’s call for emissions reductions. It is widely believed (Walsh 269) that this interpretation will not prevail in Copenhagen, as the rapid growth of these economies has become increasingly significant in terms of amounts of emissions, though many (especially in China, India, and Brazil) still disagree.

Those countries impacted by this new interpretation (China, Brazil, India), are taking the stance that if they are expected to take on commitments in terms of emissions reductions, “they should receive financial compensation for their environmental restraint” (Walsh 269). To them, their rights to growth and development should not be infringed upon because of larger environmental commitments. If this interpretation is widely held at the negotiations in Copenhagen, where will the money for these financial commitments come from?

Another area of contention regarding China, Brazil and India is the issue of scope of emissions reductions. These three nations want their reductions to be reductions in “emissions intensity,” as opposed to reductions in “emissions levels” because then their economic growth would only be hindered proportional to GDP.

Where did this idea that some nations face different obligations and rights than other nations derive? According to Professor Paul Harris of Brandeis University, in terms of climate change, the idea came about at the Rio De Janeiro Earth Summit. This concept of differentiated responsibilities gained momentum at the 1982 United Nations Convention of Law of the Sea. Also, differentiating between developed and developing countries was further justified in Principle 23 of the 1972 Stockholm Declaration which states “the extent of the applicability of standards which are valid for the most advanced countries but which may be inappropriate and of unwarranted social cost for developing countries” (Harris 29). Also, in 1995 at the Berlin Mandate, developing countries pledged to reduce their emissions before requiring developing countries to reduce emissions. (Harris 32)

So if the concept that there are differentiated responsibilities of emissions reduction is based on historical precedent, why do Whalley and Walsh predict that this interpretation will not prevail in Copenhagen? Perhaps the climate situation has just become too dire?

Tags: common but differentiated responsibilities, COP15 Resources, developing countries, Kyoto Protocol

www.treehugger.com

In Bali 2007, the topic of trade and finance in the context of climate change negotiation was brought up. This is also one of the topic that parties need to agree on in Copenhagan 2009. The idea of using trade and finance to reduce green house gases (GHG) is definitely a worthy topic. However, at the current stage of negotiation and research, trade and finance policies may not be settled in Copenhagan.

Trade affects climate change negotiation because cross border trade makes it hard to single out which countries to hold responsible for climate impact of a certain product. Carbon intensive goods such as chemicals, motor vehicles, steel and aluminum are usually produced in one country and consumed in a different country. The current policy under Kyoto Protocol hold the country of production responsible for reducing the emission. However, this is unfair to countries having competitive advantages in those products. Developing countries particularly have advantages in carbon intensive industries. Developed countries, on the other hand, focus more on services. Applying the current rule to developing countries effectively shifts the focus away from the biggest GHG emitters historically, i.e. developed countries.

The dynamics of environmental responsibilities between production and consumption countries can also be seen through the three lenses outlined in Parker’s and Blodgett’s paper titled Global Climate Change: Three Policy Perspectives. If the technological lens is applied, production countries are to blame because their technology is not developed enough to minimize emissions. Using the ecological lens, consumption countries are to be held accountable because of their excessive consumption habits.

In my opinion, whatever countries that benefit from the product should address its environmental implications. In that sense, both production and consumption countries should share the responsibilities. The harder problem would be where the balance is. After the negotiation round in Bali, there is still not enough research and data to suggest that any agreement in the area of trade will be made in 2009. As a result, as important as the issue is, it should be included only after Copenhagen 2009 in order not to delay the whole negotiation process.

Luan Nguyen.

Tags: ecological lens, Luan Nguyen, technological lens, trade

I strongly believe that the commitments resulting from the Copenhagen Conference will revolve around trade. People, countries, and the world think in terms of money; people will not simply start caring about the environment overnight. Therefore, any outcome of Copenhagen must put into financial terms in order to have nations understand the full gravity of the situation and, hopefully, their commitment.

I see the producer-pays as an intrinsic flaw in the environmental aspect of international trading; our current situation cannot be remedied without consumers bearing some responsibility in GHG emissions. Climate change is now a fact of life, an issue that can be dealt with now or later with a variety of possible consequences. Many countries are fretting over the economic downturn and how environmental regulation is going to hamper GDPs and further growth of economies. Like the first line of the foreword of Baument quoted: “We can draw lessons from the past but we can’t live in it” (LBJ). It seems to me that the world needs to face the reality that the economy isn’t going to be as good as before. We simply cannot continue to consume in our present manner.

Perhaps this is why I was shocked to learn that producers carry the full burden of GHG emissions. Under the current system, international trade creates a Catch-22 for developing countries: they are forced to pick between the economic wellbeing of their country and people, and the environment. No wonder China and India are resisting these measures: they are the countries that welcome factories of the Western outsourced companies! If the Copenhagen Conference is going to accomplish anything, I hope that it creates a mechanism that more evenly distributes the economic and GHG emission price on the consuming country. If the U.S. consumer had to take responsibility for half of the GHG emissions from everything imported from China and India, the environment would be a much healthier place merely because the U.S. would not allow as many goods to be imported. These factories will not produce things (and subsequently pollute) if we do not buy. We cannot pin the emissions on a developing country that is industrializing; we have to look at how we operate and stop putting the blame on those who are only partially responsible.

Tags: accountability, consumer accountability, consumerism, equalizing trade mechanisms, trade

Climate change and poverty

Version:1.0 StartHTML:0000000200 EndHTML:0000006837 StartFragment:0000002385 EndFragment:0000006801 SourceURL:file://localhost/Users/bettu/Desktop/blogging%20assignment%20%233%20and%20notes.doc

When negotiations over the post-Kyoto climate change regime resume in December, the issue of ‘common yet differentiated responsibilities’ is certain to generate some intense debate. Beyond the conflicts caused by the deferring interpretations of the actual wording – repeated so often that it has become the mantra of international climate change discourse – ‘common yet differentiated responsibilities’ is a problematic approach to negotiations on several other levels.

First, the definition of differentiated roles (or responsibilities) in dealing with climate change is suggestive of a moral and ideological paradigm that is not always compatible with climate preservation policy. Even if they differ in the interpretation of roles, most people seem to agree that developing nations have a “right” to grow and develop much in the same way that developed nations have. And the Kyoto protocol tried to protect this ideal by limiting or eliminating the need for commitment on the part of developing countries, regardless of their level of industrialization – a mistake that largely contributed to the protocol’s poor performance. At this point a difficult moral question is raised: Should developing countries really be allowed to grow in the traditional, carbon-intensive way without any commitments to environmental preservation? And where should the line be drawn between right to grow and develop, and responsibility to care for a common (endangered) resource? The most logical (and least morally questionable) answer seems to be the promotion of sustainable development – economic, environmental and human –in regions where the resources and knowledge are not yet available. However, outside of the exceptional unilateral action plan (you can check out other EU plans here), all mentions to this issue so far have been vague and uncommitted.

Tags: China, climate change, COP15 Resources, developing countries, India, Kyoto Protocol, poverty, sustainable development

In Bringing the Copenhagen Global Climate Change Negotiations to Conclusion, John Whalley and Sean Walsh declare that prospects for a satisfactory outcome from COP 15 are daunting. I might add intimidating, overwhelming, and frightening, but that’s just me.

We’re talking about nearly 200 countries, representing 6.7 billion people, coming together to discuss, in two weeks, a response to our precarious global predicament. Overall the goal of COP15 is to establish an ambitious global climate agreement. The issues at hand however, stretch far across any conceived, demarcated political boundaries. Each country and each individual delegate of that country has a motive and many conditions that hinge their lasting participation in whatever outcome may arise. COP negotiations in the past have been criticized for their lack of tangible, lasting conclusions. This video, created using footage from the COP14 in Poznan Poland sums up these criticisms quite succinctly.

Climate Change Humor

One disheartening barrier to success in Copenhagen is the lack of consensus on the science and severity of climate change. Those who have read the Stern Report and the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC report believe that swift strong action was required… yesterday. Today it is nothing short of imperative. The Stern report labels climate change as the largest market failure and predicts that by 2050, if we continue business as usual, could produce damaging effects – numbers like 20% – to the global economy. But there are still climate skeptics, or climate rationalists who stand by the findings individuals like Roberto Mendelsohn and his claim that the Stern Report makes assumptions that inaccurately increase the gravity of climate change. How can we expect the COP to come to an international agreement when the central driver of the negotiation is being debated?

Whally and Walsh argue the unclear and open-ended negotiation mandate may also hinder the effectiveness of the Copenhagen negotiations. At COP14 in Ponzan, participants lacked a common vision for climate change action and could not reach agreement on the scale, depth and type of CO2 cuts. Whally and Walsh argue that much of the available, valuable negotiation time will be spent figuring out these details. Other technicalities require concurrence as well: what year to use for baseline data, whether to measure emissions based on levels or intensity, per capita emissions or overall emissions, production emissions or consumption emissions- the list is very, very long. And then there is the idea of ‘common but differentiated’ responsibilities and determining what exactly this phrase involves. I think Wally and Walsh depict the core of this issue when they write, “In other words, to what extent does development toward economic, social, cultural, and other key goals within a country take precedence over environmental considerations for each country? A difficult ethical question to be sure, especially when the last few hundred years of any given countries history also weigh into any discussion on this question” (261).

The lack of dispute resolution and enforcement is also a source of concern. Currently there is a backlog of countries with unfulfilled Kyoto agreements. If the backlogs are dismissed from future commitments, countries like India, who call on Annex 1 countries to lead the way, will not be happy. If they are incorporated into future requirements, those who failed to comply will be weary to agree, as most likely, they will face discouraging reductions.

The question also arises, if the Kyoto Protocol didn’t work, why would a Copenhagen agreement be anymore sucessful? The overall perception of climate change severity and agreement on international goals for the negotiations will play a significant role in ensuring post COP15 outcomes are successful. Unfortunately these issues are still up in the air.

I think daunting accurately describes the challenges the world seeks to face in Copenhagen. We are optimistic if we think that the skeleton of an international climate change agreement can be effectively debated and assembled by 192 nations in fourteen long days. And we must remember that a skeleton then needs skin and clothes… Daunting

Whalley, J., and S. Walsh. 2009. “Bringing the Copenhagen Global Climate Change Negotiations to Conclusion.” CESifo Economic Studies 55(2):255-285.

Tags: climate change, common but differentiated, COP15 Resources

Your Comments