For those readers just joining me now, this is the second in a series of three blog posts about Dickinson College’s 1619 copy of the Catalogue and Succession of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marquesses, Earls, and Viscounts of England. (I’ve had to abridge the rather unwieldy title, which can be found in part one.) My first post was a general overview of the material book, and here I turn to the origins and the afterlife of this deceptively straightforward text.

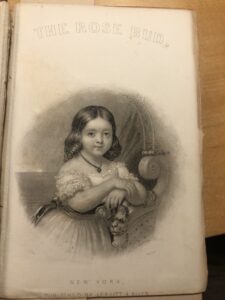

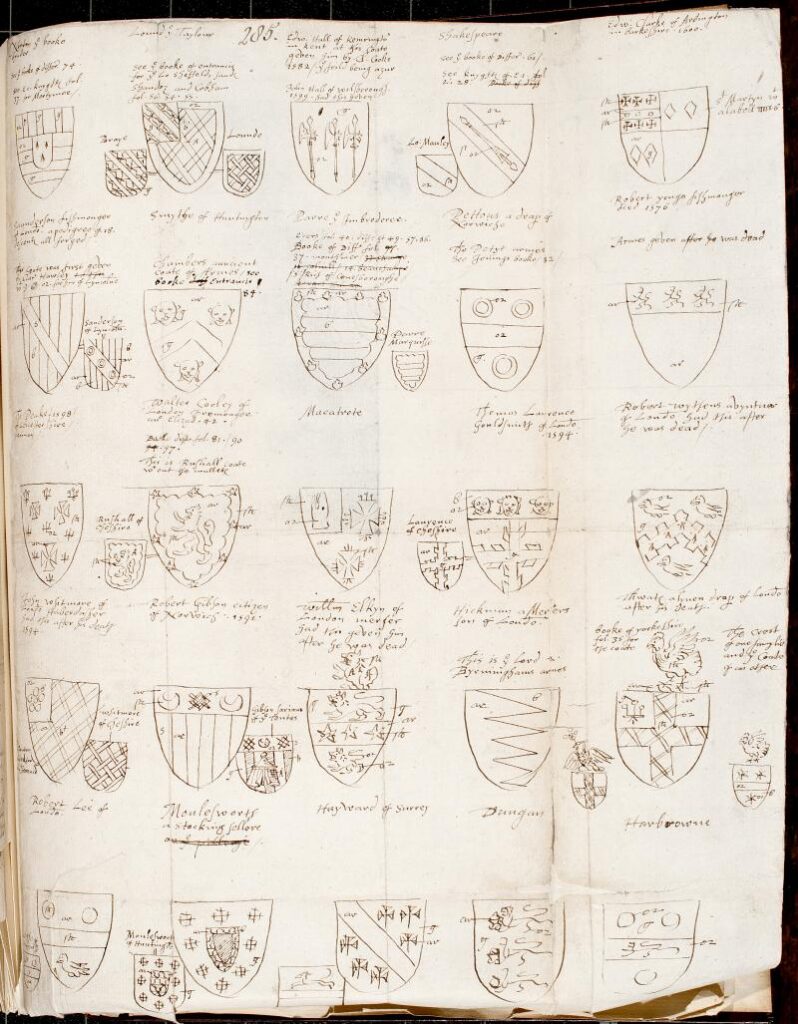

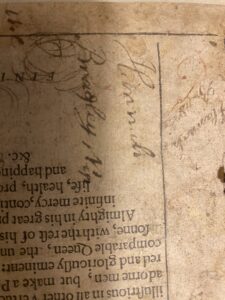

The existence of the Catalogue is inextricably linked to one man: Ralph Brooke. Brooke rose from the son of a shoemaker to York Herald in the College of Arms, where his combined desire to fight corruption in the College and his short temper regularly put him at odds with other heralds—and made him no stranger to fines and suspensions. The story of Brooke’s personality and career shines through best in the following anecdote: in 1602, he formally challenged (among 22 others) the heraldry that Garter King of Arms William Dethick had granted to John Shakespeare, the father of William Shakespeare, on the basis both of low social rank and of similarity to those of another lord (fig. 1). Brooke soon found his challenge defeated, though, by a group which included his arch-nemesis (and coworker) William Camden. Brooke’s general discontent with the College’s output, particularly Camden’s survey of the British Isles, Britannia, led him to author his own Catalogue and Succession to correct the perceived errors made by his colleagues.

Fig. 1: The arms challenged by Ralph Brooke. Shakespeare’s arms can be seen in the top row, second to the right.

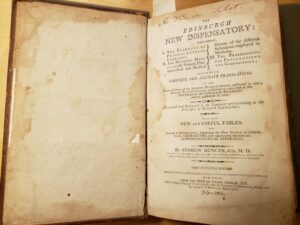

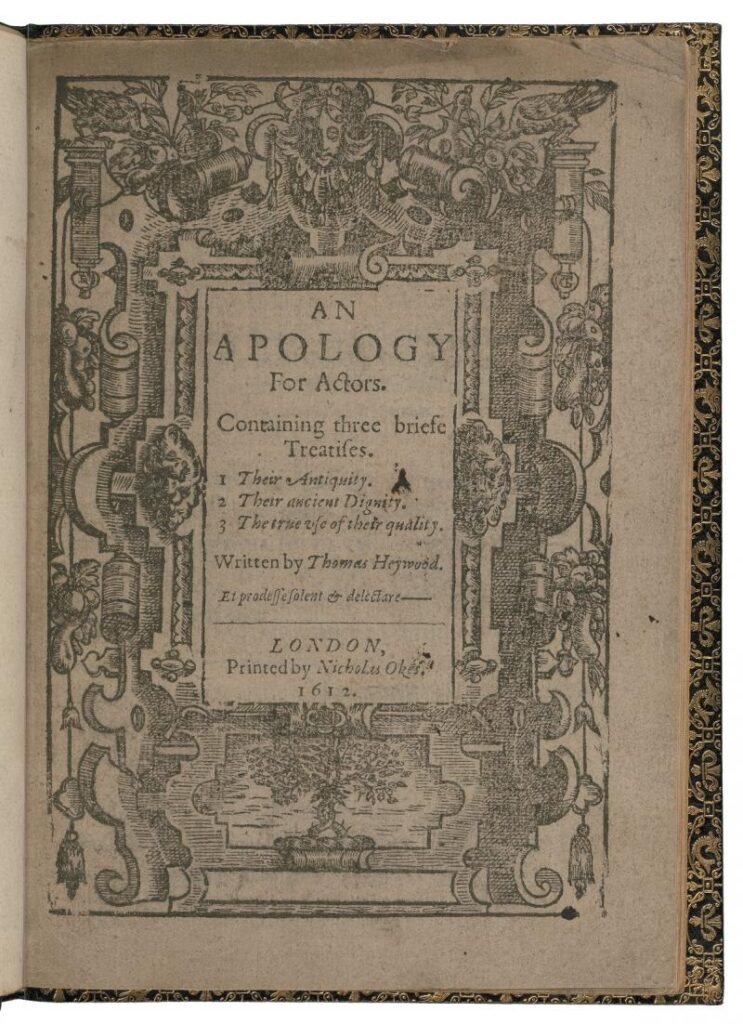

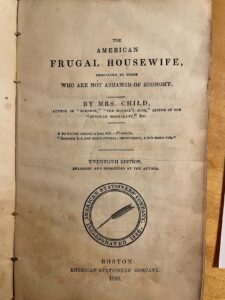

He chose William Jaggard to print it. A former apprentice of the great Henry Denham, Jaggard had by 1619 become a leading London printer and bookseller with a Crown commission for copies of the Ten Commandments. But he was hardly a paragon of honest business, and coincidentally, his own dealings with Shakespeare best establish his complicated personality. In 1599 Jaggard printed a collection of poems called The Passionate Pilgrim. The second edition, published the same year, is attributed to “W. Shakespeare”—who had written only five short poems in the entire twenty-poem volume. Jaggard also credited the 1612 expanded edition solely to Shakespeare though the only new additions were poems by Thomas Heywood; it took Heywood’s publication of his (and Shakespeare’s) disapproval to get Jaggard to remove “By W. Shakespeare” from the title page (fig. 2 depicts the title page of Heywood’s “Apology for actors”). In 1619, Jaggard falsified the dates of several Shakespeare plays so it appeared he had the rights to them; the resultant compilation has become known as the False Folio. But even after a long career spent wading in the muck of unethical business, Jaggard also printed the legitimate First Folio. William Jaggard’s dealings with Shakespeare thus reveal something of a Janus with a print shop: a man simultaneously reputable and prone to unethical action in order to make money.

Fig. 2: The title page of Heywood’s Apology for Actors.

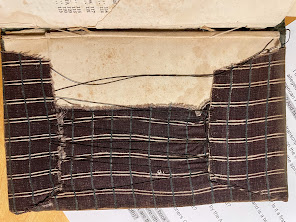

A conflict between the personalities of Brooke and Jaggard seems almost inevitable. Dickinson’s copy, which is a mess, bears the scars of the two men’s conflict. In order to determine this book’s physical origins, particularly its fraught printing process, one must consider its afterlife. We must look to the published words of Brooke and Jaggard.

Two editions of this book exist: the 1619 edition and a corrected 1622 edition in which Ralph Brooke appears more incensed than before. The title page, while it does contain much the same text as in 1619, also features this addition: “Collected by RALPH BROOKE, Eſquire, Yorke Herauld, and by him inlarged, with amendment of diuers faults, committed by the Printer, in the time of the Authors ſickneſſe” (Brooke). No printer’s name appears, but according to the catalogue entry from Duke University, Brooke has jettisoned Jaggard and enlisted the services of William Stansby, printer of Ben Jonson’s 1616 Workes.

Brooke explains the “faults committed by the Printer” in a letter addressed directly to the reader. While most of the letter accuses other heralds of enviously trying to defame him, Brooke states in the opening paragraph that he has fixed “many eſcapes, and miſtakings, committed by the Printer, whilſt my ſickneſſe abſented me from the Preſſe, at the first publication” (Brooke). He styles himself as someone who intended to regularly check in on his book during its printing, seeking a significant level of control over Jaggard’s press, and whose illness is what let the printer freely make errors. Our York Herald is not content to air his grievances in prose alone: he also includes a poem in heroic couplets. (Below this extended diatribe William Stansby chooses to include his own errata list.)

It must be noted: the comic potential of Ralph Brooke’s characteristic irritability did not escape his contemporaries. In 1622, Brooke’s coworker Augustine Vincent published A discouerie of errours in the first edition of the Catalogue of nobility, published by Raphe Brooke, Yorke Herald, 1619. This book satirizes Ralph Brooke’s Catalogue and includes testimony from numerous individuals with connections to the York Herald. One of these individuals, it happens, is the printer of Vincent’s book: William Jaggard.

In his own scathing letter, Jaggard pushes back against Brooke’s assertion that he is to blame for the errors in the 1619 edition of the Catalogue. Drawing on the original errata list, Jaggard argues that the errors are self-evidently the result of Brooke’s own mistakes in scholarship. Even the workmen at his shop “will at no hand yeelde themſelues to be fathers of those ſyllabical faults”; they too believe Brooke to be to blame (Jaggard). Here Jaggard turns Brooke’s watchfulness on its head: if he was watching the printing process so carefully, then the errors must be his, especially given that during his much-mentioned illness, “though hee came not in perſon to ouer-looke the Preſſe, yet the Proofe and Reviews duly attended him, and he peruſed them… in the maner he did before” (Jaggard). Jaggard finishes his letter pointedly with the word FAREWELL in capitals.

What emerges from the discourse between the 1619 Catalogue, the 1622 Catalogue, and Augustine Vincent’s Discoverie is a decidedly combative printing process. One wonders whether Brooke’s meddling is why most of the engravings are missing in the 1619 edition, why the page numbers are messy, and why the title page has been glued in. It must be said, of course: the biographies of Brooke and Jaggard alike give legitimate reason to distrust both their accounts, for one was prone to bad-faith criticism, the other repeatedly conducted dishonest business, and both were openly keen to preserve their reputations. Their conflict, though, is self-evident, and the book seems to have been the main casualty.

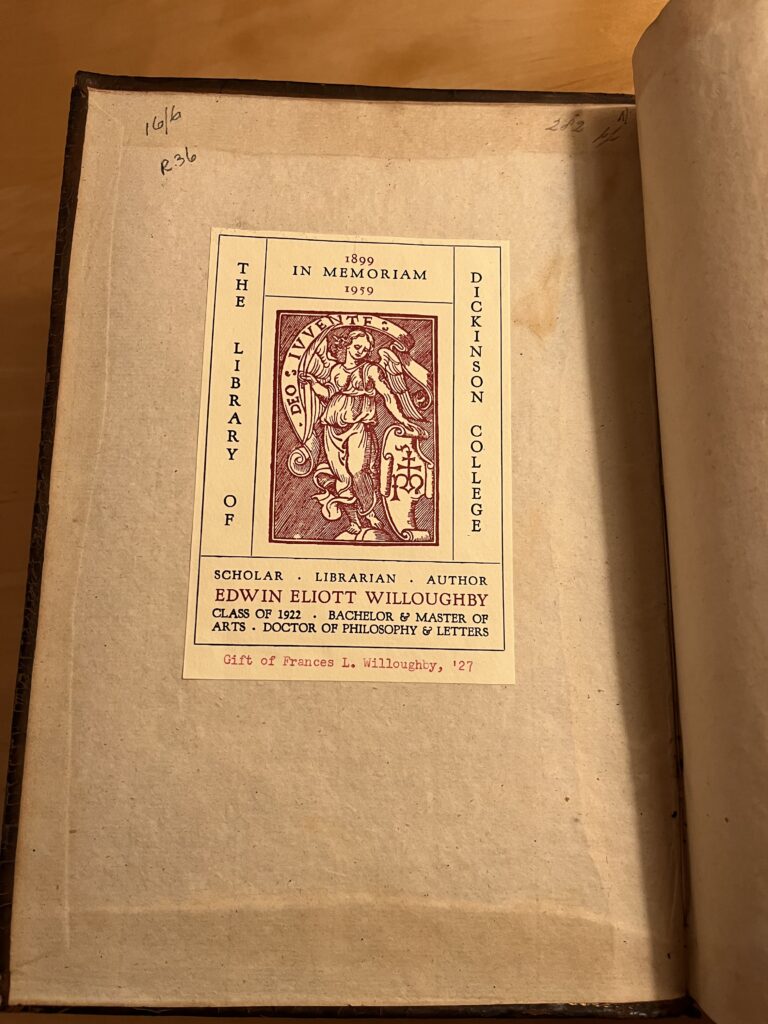

The afterlife of Ralph Brooke’s Catalogue is a quiet one after 1622. Brooke and Jaggard were both dead by the middle of the decade. From the 1640s to 1660, the Civil War and Interregnum resulted in the death or exile of countless nobles and lasting changes to the English governmental structure, rapidly making Brooke’s text—either edition—obsolete. It is telling, I think, that Dickinson’s 1619 edition bears the marks of a single early modern reader, one Sir Samuell Thomas Newman, who annotates it according to the errata list in 1640. (More on him in my upcoming “Audience” post.) The only later marks establish the book as the property of Edwin E. Willoughby and then Dickinson College (fig. 3). When Dickinson acquired the book from his sister Col. Frances Willoughby, the provenance did not come with it, so the text attests only to the ownership of Newman, Willoughby, and Dickinson College.

Fig. 3: The bookplate in Dickinson’s copy of the Catalogue.

What seems abundantly clear, regardless of how it got from Newman to Willoughby, is that this book was rarely used. Because Brooke failed to acknowledge that his work was collaborative, its quality suffered, and his book gradually faded from memory as anything more than the ranting of an irritable herald whose printer happened to also print the First Folio. Ralph Brooke, were he alive today, would likely hate to hear that William Camden’s Britannia is considered a milestone in English literature, while the Catalogue has become obscure.

Works Cited

“Book Descriptions: Glossary of Terms.” Book Addiction UK, 2023, bookaddictionuk.wordpress.com/book-collecting/book-descriptions-glossary-of-terms/.

Brooke, Ralph. A CATALOGVE and Succeſsion of the Kings, Princes, Dukes, Marqueſſes, Earles, and Viſcounts of this Realme of England, ſince the Norman Conqueſt, to this preſent yeare, 1619. London, William Jaggard, 1619.

—. A catalogve and succession of the kings, princes, dukes, marquesses, earles, and viscounts of this realme of England, since the Norman conquest, to this present yeere 1622. London, William Stansby, 1622. <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100072842>

—. The Armes presented vnto her Maiestie with the first [..] par Garter Dethecke. 1602, .

Bland, Mark. “Stansby, William (bap. 1572, d. 1638), printer and bookseller.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-64163>

Herendeen, Wyman H. “Brooke [Brookesmouth], Ralph (c. 1553–1625), herald.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-3552>

Heywood, Thomas. An apology for actors. 1612, shakespearedocumented.folger.edu/resource/document/apology-actors-thomas-heywoods-reply-passionate-pilgrim.

Vincent, Augustine. A discouerie of errours in the first edition of the Catalogue of nobility, published by Raphe Brooke, Yorke Herald, 1619, and printed heerewith word for word, according to that edition. London, William Jaggard, 1622. <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100578650>

Wells, Stanley. “Jaggard, William (c. 1568–1623), printer and bookseller.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. <https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-37592>

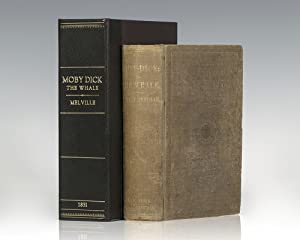

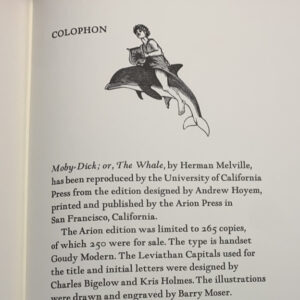

most prominent force in the company. He was closely involved in the executive decisions for design and course of action for the book, and oversaw the mechanical tasks regarding the production of the text (“About Arion Press”, www.arionpress.com). Moreover, the team of Bigelow and Holmes toiled over the design of the custom-made Leviathan typeface, attempting to bring the significance of the writing into a visual composition. For the bulk of the text, Bigelow and Holmes used the Goudy modern font, a variation of the Goudy open with the letters filled in (“Goudy Modern in use”, www.fontsinuse.com). Moreover, Barry Moser was commissioned to complete 100 wood-engraved illustrations for the book, and he was challenged by restrictions to not portray pivotal action scenes or major characters (“A Note on the California Edition”). Notably, the book is a clear distinction from identically mass-produced works, in which excellence is sacrificed for a lower price.

most prominent force in the company. He was closely involved in the executive decisions for design and course of action for the book, and oversaw the mechanical tasks regarding the production of the text (“About Arion Press”, www.arionpress.com). Moreover, the team of Bigelow and Holmes toiled over the design of the custom-made Leviathan typeface, attempting to bring the significance of the writing into a visual composition. For the bulk of the text, Bigelow and Holmes used the Goudy modern font, a variation of the Goudy open with the letters filled in (“Goudy Modern in use”, www.fontsinuse.com). Moreover, Barry Moser was commissioned to complete 100 wood-engraved illustrations for the book, and he was challenged by restrictions to not portray pivotal action scenes or major characters (“A Note on the California Edition”). Notably, the book is a clear distinction from identically mass-produced works, in which excellence is sacrificed for a lower price.