The great impresario of the Ballet Russes, Serge Diaghilev, not only created a prominent art movement, but he also contributed to the downfall of its historic remembrance. By strictly controlling the viewing of Ballet Russes productions and prohibiting video recordings, many documents were not properly archived or were simply never recorded. This means that while the most famous performances have been continued into modern times, many popular performances of the day, which fell out of the repertoire, now exist only in fragments. ((Jack Anderson, The One and Only: The Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo (New York: Dance Horizons, 1981), 263)) Thus while the legacy continues to inspire new artists, their magic is dissipating, hampering future art enthusiasts from experiencing the full works, the complete gesamtkunstwerk of the Ballet Russes. ((Adrian George, “The Art of Dance”, Dance Theatre Journal 18, no. 2 (2002): 20.))

In many aspects of the Ballet Russes Diaghilev was forward thinking and cognizant of evolving media forms and platforms, however he ignored the largest growing media of video recordings almost completely. Diaghilev stated that he banned video recordings of his productions in order to “protect theatrical box office earnings”, however a single thirty-second clip rehearsal of Les Sylphides has evaded the redaction of Diaghilev. ((Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes, produced by the National Gallery of Art (2013), DVD.)) It is unclear how the illegal recording was produced; all that is gained from the short clip are women rehearsing outside in the Swiss resort of Montreux. ((Ibid)) While Diaghilev encouraged and surrounded himself with artists of diverse backgrounds and talents, the one neglected art form was video. Diaghilev was not usually obstinate when considering new technologies on the rise, even the relatively new practice of specific lighting of performances captured Diaghilev’s attention, as he personally choreographed the lighting for the majority of productions, it was the specific art form that seemed to bother him, however the lighting of performances remains to be incomplete because interpretations of documentation (when it exists) vary for every historian. ((Barry Jackson, “Diaghilev: Lighting Designer”, Dance Chronicle 14, no. 1 (1991): 3, 12))

Cast of Les Sylphides in London 1911, courtesy of wikicommons. ((available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Les_Sylphides_London_1911.jpg))

Without film documentation, each aspect of the Ballet Russes can be reexamined separately, but in separating the components each contribution looses some of its significance. One of the long time choreographers of the Ballet Russes, Leonide Massine, actively archived his work for future use, but even these efforts are only partially recovered. ((Anderson, 263)) It is possible for diligent choreographers and dancers to collaborate in the modern day and piece together parts of formerly popular librettos, as when the three lone recoverable sections of Seventh Symphony were revived in 2004. ((Ibid)) Diaghilev was not against taking inspiration from film, as in Parade produced in 1917. ((Robert C. Hansen, Scenic and Costume Design for the Ballet Russes (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1985), 59)) Abstract costumes in the cubist style of two managers along with a Chinese Conjurer dance along side an American girl inspired by Hollywood actresses of the day, while sounds of modernization blare in the background; typewriters, horns and contrasting sounds mimic an industrial city center. ((Ibid.; Lynn Garafola, “Dance, film, and the Ballet Russes”, Dance Research: The Journal Of The Society For Dance Research 16, no. 1 (Summer 1998): 15))

The French and the New York Manager from Parade, courtesy of wikicommons. ((available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Costumes_du_ballet_Parade_(Les_Ballets_russes,_Op%C3%A9ra)_(4555465155).jpg))

Leonide Massine as the Chinese Conjurer of Parade, courtesy of wikicommons. ((available at https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:L%C3%A9onide_Massine_(Ballets_russes,_Op%C3%A9ra)_(4564734593).jpg))

While Diaghilev attempted to protect he artistic creations produced by the Ballet Russes, he ultimately hindered the longevity of performances by excluding video or archival recording of productions. The most visually alluring aspect of the Ballet Russes was the costumes and their interplay of motion with the music, but this combination cannot be observed for all productions anymore because choreography has been lost and hinders recreations of the masterpieces. Due to the lack of many complete remaining works of the Ballet Russes, modern ballet companies have developed to carry on traditions of Diaghilev, and explore their own methods of art expression, including direct descendants The American Ballet Theatre, New York City Ballet, and the San Francisco Ballet Company are direct descendants of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. ((Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes, produced by the National Gallery of Art (2013), DVD.))

Given the result of eschewing new technology, would Diaghilev reconsider his decision if he could have seen into the future? It is likely he would not. Revolutionary artists understand that great art combines talent and vision, but is a product of its time and place, and that art is something vital which everyone has the potential to actualize. How we perceive the world affects everything we do; art is a way of seeing and being – impacting not only our senses but our conception of reality. Art as inspiration, not imitation – finding one’s voice –is an endeavor that Diaghilev would applaud. Everyone has their seed of creativity to discover and develop in their own way.

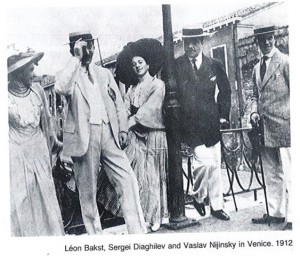

Photograph in Venice, 1912. ((Leon Bakst, Léon Bakst: Set and Costume Designs, Book Illustrations, Paintings and Graphic Works, Comp. Irina Nikolaevna Pruzhan, (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Viking, 1987), 217))