The opening seasons of the Ballet Russes in Paris was a unique explosion and intermingling of culture, merging east and west into an entirely new modern style. At the head of this movement was Leon Bakst, who was the chief designer for the Ballet Russes from 1909 to 1913. Bakst became synonymous with the Ballet Russes in these opening seasons, as he introduced Europe to the mysterious Russian culture and color palette. Through Bakst’s artistic vision, the Ballet Russes ushered in a new modern era of design by infusing ‘oriental’ aspects into then drab and bland fashions of the day in Paris, which have held lasting influences permeating multiple spheres of society, chiefly every day and high fashion.

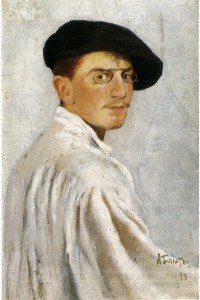

Self portrait of Leon Bakst 1893. ((Leon Bakst, Léon Bakst: Set and Costume Designs, Book Illustrations, Paintings and Graphic Works, Comp. Irina Nikolaevna Pruzhan, (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Viking, 1987), 125))

In designing for the Ballet Russes Leon Bakst kept in mind Serge Diaghilev’s goal of the German term gesamtkunstwerk, or the total work of art in order to display Russians ability to be refined and cultured and dispel the stereotype of Russians as uncultured barbarians. ((Adrian George, “The Art of Dance”, Dance Theatre Journal 18, no. 2 (2002): 20.; Christine Ruane, The Empire’s New Clothes: A History of the Russian Fashion Industry, 1700-1917 (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2009), 180.)) In order to achieve this total work of art Bakst was heavily involved through the entire creative process of the ballets which he was involved with, from the conception of costume movement through choreography to the coordination between the costumes movement against scene backdrops. In the opening seasons of the Ballet Russes in Paris, Diaghilev was under immense pressure to succeed and prove his place among Parisian society, and he put much of his faith in Bakst. A few years before Bakst began designing for the Ballet Russes, his 1908 work ‘Acacia Branch Above the Sea’ astonished viewers with it unexpected composition and color scheme, deftly combining vibrant blues, greens, yellows and pinks. ((Leon Bakst, Léon Bakst: Set and Costume Designs, Book Illustrations, Paintings and Graphic Works, Comp. Irina Nikolaevna Pruzhan, (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Viking, 1987), 14)) When designing ballets Bakst was able to retain this spontaneity and allowed these ideas form years prior to influence the color theory for his Oriental ballet designs. Of the three oriental themed ballets Bakst produced, Cleopatre, Scheherazade and Narcisse, by far the most notable was Scheherazade.

Acacia Branch Above the Sea, 1908. ((Leon Bakst, Léon Bakst: Set and Costume Designs, Book Illustrations, Paintings and Graphic Works, Comp. Irina Nikolaevna Pruzhan, (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Viking, 1987), 158))

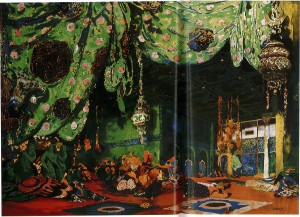

Set Design for Scheherazade. ((Leon Bakst, Léon Bakst: Set and Costume Designs, Book Illustrations, Paintings and Graphic Works, Comp. Irina Nikolaevna Pruzhan, (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Viking, 1987), 24))

A box office sensation of the ballet’s second Paris season, Scheherazade brought life to the artistically stagnant Paris art scene. When the curtain first rose on the set for Scheherazade in 1910, audiences were so enthralled with the color contrasts that the theater burst into applause, anticipating the spectacle to come. ((Robert C. Hansen, Scenic and Costume Design for the Ballet Russes (Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1985), 25.; Suzanne Massie, Land of the Firebird (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1980), 437.)) Prior to the travels of the Ballet Russes, Russian culture was stereotyped as barbaric and backwards, nonetheless the public changed their opinion once they set eyes on Diaghilev’s total work of art. ((George, 20.)) One critic called this performance “Bakst’s debauch of color”, and Scheherazade truly was the Parisians first foray into Eastern art and color theories because Parisians had become accustomed to muted colors on the stage and in fashion houses. ((Massie, 437, Bakst, 176))

Europe had been infatuated with the mysterious East, and the Parisian audience at long last got a taste of the ‘exotic’, readily embracing the colors, designs and attitudes of the Orient. Parisian couturier House of Worth exemplifies trends before the influences of the Ballet Russes were materialized in the corseted dress below, creating an hourglass figure, constructed with muted and pale colors of beige, pink and grey. This dress is reminiscent of imperial court clothing, and the backlash to the extreme structure came in the form of reinterpretations of Bakst’s costumes in clothing. The slim silhouette rose in popularity along with brighter colors, usually as embroidery, and comfort in less restrictive materials. ((Bakst, 178)) As the predominance of Bakst inspired clothing rose, popularity of Scheherazade parties among women became fashionable, where they would wear harem pants, turbans and other loosely fitting clothing, creating a new and modern social scene ((Diaghilev and the Ballet Russes, produced by the National Gallery of Art (2013), DVD.))

A woman in evening attire in 1915. ((Christine Ruane, The Empire’s New Clothes: A History of the Russian Fashion Industry, 1700-1917 (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2009), 180))

Before and after the influence of the Ballet Russes on Parisian style. ((Christine Ruane, The Empire’s New Clothes: A History of the Russian Fashion Industry, 1700-1917 (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2009), 178))

Scheherazade truly was a seminal production of the Ballet Russes, marking a defining moment in the creation and development of modernity. ((Bakst, 177)) As one British photographer recorded, seemingly overnight Parisians shed the restraining corsets, lace, feathers, and pastel shades in favor of vivid colors, harem skirts, beads, fringe, and voluptuousness silhouettes. ((Ibid., 178)) In his costume designs Bakst intended for his costumes to be “inseparable from the dance”, this interdependence and emphasis on motion and comfort for the dancers also served to free modern women from the constraints of heavy and drab clothing. ((Michelle Potter, “Designed for Dance: The Costumes of Léon Bakst and the Art of Isadora Duncan,” Dance Chronicle, 1990, 168)) Though to a lesser degree men also experienced liberation from former dress constraints and greater allowances in expression through clothing. ((Ruane, 178))

The unintended fashion revolution initiated by Bakst’s costumes gave way to an altered body image through the fusion of the East brought to the West by Diaghlev. The “modernist body” image created space for the Parisian couturiers to expand upon the ballet costumes to daily attire. ((Ibid., 179)) Bakst had suddenly become the authority on modern fashion, with the top couturiers of the day drawing inspiration from Bakst’s designs along with inter design following suit with oriental furniture, textiles, and designs coming into fashion. ((Bakst, 25)) Historically, ballet costumes restricted dancers’ movements with tight tutus, slippers and fabrics with exotic motifs, but displaced on similarly constructed garments. ((Roger Leong, From Russia With Love: Costumes for the Ballet Russes 1909-1933 (Australia: National Gallery of Australia, 1998), 40)) In his desire to bring greater historical accuracy in costume design, Bakst also provide dancers with more natural body motions and freedom of expression of sexuality and androgyny. ((Ibid.))

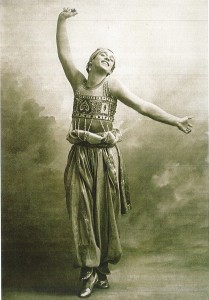

Vaslav Nijinski as the Golden Slave in Scheherazade. ((Roger Leong, From Russia With Love: Costumes for the Ballet Russes 1909-1933 (Australia: National Gallery of Australia, 1998), 57))

Vaslav Nijinski and Isadora Duncan challenged androgyny and sexuality of stage fashion in Europe, eliciting emotional expression in their audiences. Nijinski was an exceptional dancer who gracefully explored the boundaries of masculinity in his dance roles, displaying Bakst’s creations to wide audiences. The inspiration of Isadora Duncan led Bakst to develop the famous costumes for Nijinski as his muse. ((Potter, 158)) As an advocate for freedom of motion to increase choreographic integrity, Isadora performed in sheer and un-constricted costumes to allow form and rhythm to correspond. ((Ibid., 166)) In designing stage wear, Bakst often put music as a later consideration, but through the inspiration of Duncan Bakst gained an awareness of movement in relation to the libretto ((Leong, 36)) The new freedom of women’s clothing brought on through Duncan’s guidance was a welcome change because it gave women greater opportunities to directly participate in the artistic movement while challenging social norms. ((Ibid., 158)) Parisian society at the time was receptive to radical ballets like Scheherazade because society was anxious for a catalyst of change. At the time the nouveaux riches and déclassé aristocrats were challenging the cultural hegemony of the ruling elites in France, as the Ballet Russes simultaneously challenged decades of prescribed dance form and theater. ((Ruane, 177)) As described by Ruane, the “emotional content of the ballet converged with the emotional needs of the audiences”; this connection intertwined the Ballet Russes and France from that point forward in the journey to modernization. ((Ibid.))

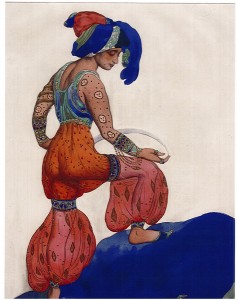

The Blue Sultan from Scheherazade. ((Christine Ruane, The Empire’s New Clothes: A History of the Russian Fashion Industry, 1700-1917 (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2009), 174))

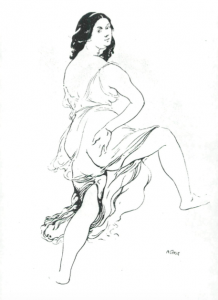

Isadora Duncan sketch by Bakst. ((Leon Bakst, Léon Bakst: Set and Costume Designs, Book Illustrations, Paintings and Graphic Works, Comp. Irina Nikolaevna Pruzhan, (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England: Viking, 1987), 160))

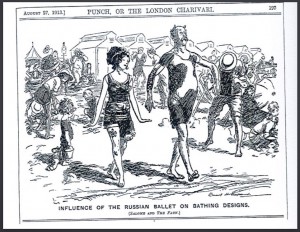

Although one of the original factors that brought the Ballet Ruses to Paris was the goal of strengthening Russian and French relationships in the hopes of gaining financial aid, the company also carried other aspirations. In the early 1900s France was one of the leading powers of the world, while Russia was in economic turmoil. The Ballet Russes personified the Russian peoples’ desire to become a successful Asian colonial power and eventually compete with Britain and France. ((Ibid.)) By modernizing and absorbing France’s way of life and presenting the Eastern Russian culture as legitimate interpreters of the western traditions, French culture also became imbued with new perspectives on culture. ((Ibid.)). Fashion was one sphere in which the Russians had the upper hand of influence in the early 1900s, as the Scheherazade design became a fashion craze. The larger implications of this impression spread Russian culture as a modern authority on expression of sensuality of music through color and design choices throughout Europe, allowing Russian designers to be accepted into high couturier circles of fashion. ((Ibid., 180, Bakst, 24)) the new definition of modern fashion sensibilities developed from a synthesis of East and West; firmly rooting and defining modernity in the growing global economy and flow of fashion and ideas.

Newspaper satire of the European’s adaptation of Russian fashion. ((Christine Ruane, The Empire’s New Clothes: A History of the Russian Fashion Industry, 1700-1917 (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2009), 176))

Part 1: http://blogs.dickinson.edu/quallsk/2016/05/03/ballet-russes-the-early-years-part-1-of-6/

Part 3: http://blogs.dickinson.edu/quallsk/2016/05/03/the-loss-of-gesamtkunstwerk-part-3-of-5/

Part 4: http://blogs.dickinson.edu/quallsk/2016/05/03/images-of-the-ballet-russes-part-4-of-5/

Part 5 (bibliography): http://blogs.dickinson.edu/quallsk/2016/05/03/original-proposal-and-bibliography-part-5-of-5/