Author Archives: Frank Kline

Nationalism in a Multiethnic Country

Karl Marx writes on how the revolution of the proletariat will bring down national boundaries, and that class will unite and bring people together in the same way that nations did in the past. With a land mass as extensive as the Soviet Union had, the number of cultures, languages, and traditions are nearly infinite. However, the problem that the Bolsheviks faced was that they needed to unite the peasants in some manner to get them to overthrow the tsarist regime, so they attempted to unite under a common Russian identity. The major ethic groups such as the Tatars, Chuvash, and Caucausian peoples wanted to keep their traditions which had been in place for centuries if not more. ((Slezkine, 421)) Clearly they wanted to stand up against this, but the nationwide reforms the Soviets sought to put into place required some basic language or national unity for efficiency’s sake.

This quickly deteriorated into a very pro-Russian ethnic idea. It was epitomized by a man who was Georgian by birth, Stalin. The people who were not Great Russians were the victims of tsardom, and were backwards, and in order to reverse this backwardness, they needed to be educated by the party in all aspects of life. They would have to, “Develop and strengthen their own Soviet statehood in a form that would correspond to the national physiognomy of these peoples.” ((Slezkine, 423)) The Soviets met all of these cultures at the middleground, they allowed them to preserve their languages in things such as their courts and arts, but bow down to Soviet dominance in other aspects of life.

This is not to say that the Soviet Union made it easy for these cultures to survive, the process for a language to become official was extremely arduous. The failure to go along with Stalin’s policies or the party line would end in harsh punishments for that group.

With the large groups of nationalities, controlling them according to the needs of Stalin and the party was always going to be a harder task, especially when some of them do not feel the need to contribute back to Moscow.

Yuri Slezkine, “The USSR as a Communal Apartment, or How a Socialist State Promoted Ethical Particularism,” Slavic Review, 53, 2, 414-452

Purging for the Good of the State

Stalin had a clear agenda for what he wanted to get done in the Soviet economy. The base of the society rests on if they can get food, so naturally agriculture is very important to the success of an economy. Due to the poor results he was getting from the agricultural sector, he sought to find new ways to inspire production from the Soviet people.

Interestingly, the dominant force within Soviet argriculture were the kulaks, the peasants who controlled the majority of production or were doing well for themselves. While the term represented a large spectrum of wealth, they were an oddball in a socialist country. Stalin saw these people to be enemies of the state and began to discredit them through party agitators and eventually began to purge them. (( http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1929-2/collectivization/ )) Stalin realized that these kulaks did hold a tremendous amount of power on a local level, which matters more to the everyday lives of the Soviet citizen. In his essay regarding the grain crisis, he reiterates that those who seek to return to kulak farming are similar to that of the great serf estates of the tsarist regime. (( http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1929-2/collectivization/collectivization-texts/stalin-on-the-grain-crisis/ )) He also mentions that the kulak is the antithesis of communism, and for that reason alone, it should not be allowed. Stalin mentions how the kulaks have lost a large amount of power in the years leading up to his writing, and now they can finally bring the power of the kulaks into the realm of the state so that it can produce for everyone. (( http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1929-2/collectivization/collectivization-texts/stalin-on-the-liquidation-of-the-kulak/ ))

A year after his essay on the liquidation of the kulaks, Stalin writes in the party newspaper, Pravda, that the successes of liquidating an entire class of people has been phenomenal for the state as a whole. The success was “dizzying” and this sets a very dangerous precedent for the rest of Stalin’s reign. He is justifying the murder of his own people for the good of the state and the party. He sees success in the rural community through his destruction of the kulaks, writing, “It shows that the radical turn of the rural districts towards Socialism may already be regarded as guaranteed.” (( http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1929-2/collectivization/collectivization-texts/dizzy-with-success/ )) By defending murder for the good of the state, Stalin is tightening his grip on the Soviet Union more and more.

The rural parts of the Soviet Union were always going to be the hardest to adjust to socialism, and Stalin believed that drastic steps were needed to impose it upon them. By removing their local “lords” and replacing them with the state, Stalin is taking the steps towards having socialism entirely in one country.

Revolutionary Poetry

With the rise of literacy in Russia, literature became a more effective way to spread ideas throughout the people. Poetry stands out from the other forms here due to it’s rhythm. It is easier to remember stanzas of poetry than prose. This makes poetry a fantastic way to spread revolutionary ideas as well as the cost of the revolution.

Maksimilian Voloshin writes about how often progress is reached by some sort of sacrifice. In his poem, “Holy Russia” he describes the destruction that has come as a result of the revolution. “You yielded to passion’s beckoning call, And gave yourself to bandit and to thief, You burned your barns and fired your mansions, Pillaged your ancient house and home, And went your ways reviled and wretched, The handmaid of the humblest slave.” (( Voloshin, Holy Russia, http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/culture-and-revolution/culture-and-revolution-texts/holy-russia/ )) Voloshin tells of a Russia that has been torn apart by revolution, but that has the ability to make tremendous progress, something that would be positive to hear after years of brutal civil war.

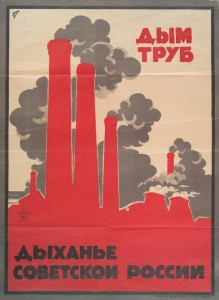

Meanwhile, poets such as Kirillov and Gastev wrote on the glorious aspect of the revolution that came out of industrialization. In the poems, “Iron Messiah” and “We Grow Out of Iron” a new, magnificent future is made possible by the revolution, which was made possible by the machine. The machine allowed the proletariat to rise, and it will continue to allow for equality. Kirillov writes, “All of steel, unyielding and impetuous; He scatters sparks of rebellious thought,” this emphasizes the importance of technology in the minds of the revolutionaries. ((Kirillov, Iron Messiah, http://soviethistory.msu.edu/1917-2/culture-and-revolution/culture-and-revolution-texts/the-iron-messiah/ )) The machine represents power, equality, and progress, all which were goals of the revolution. This can be seen in the writing of Gastev, “I shall not tell a story or make a speech, I will only shout my iron word: “Victory shall be ours!”” ((Gastev, We Grow Out of Iron)) The use poetry to expand this message to the people emphasizes the importance of continuing to produce for the state using the technology that set them free.

These poets help to inspire the people that this suffering during the revolution is for a greater cause, but also that the very machines that made their lives harsh were the ones that liberated them. I think it is very interesting how the description and imagery of heavy machinery would fit right into a Western capitalist propaganda ad, but it can also be used to inspire the workers.

“The smoke of chimneys is the breath of Soviet Russia” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Soviet_Union_(1927–53)

Russian Demographics

While we often hear about the Russian monarchy not having that much Russian blood, that is also associated with the mass of the Russian Empire. Many of the people living within the borders of the Empire have a different ethnic identity than simply Russian. Many of them are “Little Russians”, this can mean either Belorussian or Ukrainian. However, they were counted as Russian, in the Census of 1897. Actually, over half of the people living within the borders were not ethnically Russian. While there was no group bigger than the Russians, the massive empire was bound to include numerous ethnic groups and identities from all over. This not only includes ethnic identity but all the cultural aspects that comes with that such as religion and tradition. With the expansion of the Russian Empire, it brought on these new religions and traditions that were previously not as dominant in Russia. Despite this, it seems that the Russians did not fare considerably better than their counterparts most of the time. Excluding the nobility, most Russians were in worse shape than the other ethnic groups at the time the census was taken. Even the nobility was mostly a different ethnic group. With many of the Russians tied down to serfdom for centuries, their rise to the higher social standings was difficult to come by.

Another interesting aspect of the census was the effect industrialization had on society. Some groups were much more concentrated in urban areas, notably the Jews, more than fifty percent reported to live in the cities. The development of industrialization was led by the Russians however. “Yet the majority of entrepreneurs were Russians and foreigners, and the majority of the workers Russians.” ((Kappeler 304)) As I mentioned earlier, the fact that many of the Russians were serfs and then freed allowed them to move into the cities to help participate in this industrialization. This industrialization also involved a few key ethnic groups which linked them to the cities. Their involvement from all ends of the empire led to the rapid development of train tracks which was massive for development in Russia.

The census not only helps show that Russians were not as dominant an ethnic force as they would like you to believe, but also helps us understand how industrialization went the way it did.

What prevented other ethnic groups from getting involved in industrialization?

Works Cited

Kappeler, Andreas. (Translated by Alfred Clayton) “The Late Tsarist Multi-Ethnic Empire between Modernization and Tradition.” Longman, 2001. Chapter 8

An Enlightened Monarch

Catherine establishes many new reforms for establishing the bureaucracy as well as containing the power of the nobility. With the military commanders set up by Peter the Great removed after his death, Catherine establishes a new system for governing the massive expansion of land that is Russia. She appoints the leaders for these provinces, so they are loyal to her and thereby she centralizes her power. What makes these reforms Enlightened however are the responsibilities she gives to these governors, as well as the fact that she is writing all of these, taking an active role in her governance. These administrations are expected to establish welfare systems, build bridges and roads for the people, as well as education, orphanages, and poor houses. ((Kaiser, Daniel H. and Gary Marker. Reinterpreting Russian History: Readings 860-1860s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994. 242)) It was not simply just a way for her to control Russia, but she reflects what Peter did in establishing things for the good of the Russian people, not only her own power. The Enlightenment ideals that clearly had a hold on Catherine’s mind are shown here as she seeks to educate her people, and take care of them but also the absolutist ideals of autocratic rule. The picture shown at the bottom demonstrates how Catherine wanted people to know that she was actively involved in the process of writing the law as well as enforcing it.

Catherine demonstrates a tremendous amount of skill by allowing the nobles to have a small amount of power and in return she stays on the throne. ((Kaiser 245)) Her vision of uniting Russia under her rule to become a more educated state, as well as one that took care of it’s people is shown in her law codes and charters. While she undoubtedly put many people in serfdom, she sees the majority of this going towards the glory of the state. By establishing schools and a welfare system throughout the country, she is making Petersburg closer to everyone through a more progressive way. This is truly enlightened as she realizes that Russia must move forward, but she also preserves many of the traditions as she knows her legitimacy is shaky.

How does her vision compare and contrast with the vision of Peter the Great?

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catherine_2_nakaz.JPG

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Catherine_2_nakaz.JPG

The Iron Bridle

Peter the Great was certainly a man of directness. Whether it was his reforms to westernize Russia or slaughtering those who opposed him, it was his way, or the highway. Through his reforms, the trend of servitude to the state for the sake of westernizing sticks out like a sore thumb. Peter enforced an education requirement for rights, while it seems harsh and that those rights should be unalienable, the education would teach the men to serve the state. These services were often directed towards progress and advancing the country towards what Peter wanted. He wanted people to have the same desire for progress that he had. “Peter wanted for Russia an elite composed of individuals capable of taking an active role in transforming society.” (Kaiser 247) He was such a passionate and powerful figure that he seized Russia with the iron bridle and dragged her with him to wherever he thought was best.

Peter’s desire to westernize was portrayed in many different ways, but through self portraits and statues, he shows a very clear image of how people should look. The Cap of Monomakh and emphasis on the Church was gone, in it’s place was well trimmed facial hair and clothing that would appear in a western European court.

Peter’s desire to westernize was portrayed in many different ways, but through self portraits and statues, he shows a very clear image of how people should look. The Cap of Monomakh and emphasis on the Church was gone, in it’s place was well trimmed facial hair and clothing that would appear in a western European court.

His directness in getting what he wanted shines through in his Table of Rank. Peter established a hierarchy in the military and civil service that allowed him to give out rewards for serving the state. It was a way to undermine boyars, similar to how Ivan gave out control in the appanage system. By their way of achieving rank through the actions of Peter, they were more loyal to him. People could now go and achieve higher stations in society by serving the state. This new nobility could be passed down hereditarily as well, adding even more incentive to give one’s life to the state. (Kaiser 229) The Chin system allows for Peter to have nobility that are dedicated to serving the state rather while at the same time serving their own personal interests. He brilliantly combines their personal interests with the path to achieving higher levels of nobility.

How effective was the Table of Rank, and did it the newer nobility have any authority in society?

Daniel H. Kaiser, and Gary Marker. Reinterpreting Russian History: Readings, 860-1860’s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

https://pixabay.com/en/statue-bust-head-monarch-peter-l-315430/

Ivan the Power Hungry

Ivan’s rule was centered around the pursuit of power for self preservation. After seeing so many of those close to him dying, whether it was the suspicious death of his mother, or the tragic death of his beloved wife, death had surrounded Ivan from a young age. Many of the actions he took were strengthening the central government in Moscow by directly enhancing his own power and giving billets in local government to his supporters, but he also gave power out to loyal servants, “oprichniki” to do his bidding. These oprichniki acted in unrestricted violence to do whatever Ivan told them. Their violence towards boyars, churchmen, and normal citizens were truly terrible.

In the account of a foreigner, Heinrich von Staden, working as an oprichniki he described some truly sadistic punishments that were directly ordered by Ivan. His bloody and merciless path to find who was against him cost many innocent people their lives. (Kaiser 153) However, this is the account of a foreigner who used these stories to try and convince the German Emperor to invade Muscovy. The actual twisted nature of Ivan can not be accurately found in these accounts.

However, the boyars were not simply useless to Ivan, he did strengthen the boyars who supported him, again showing how he was seeking power to protect himself. It was quite natural for leaders during this time to consolidate power and kill people who opposed them. The Western idea of Ivan and “the Terrible” can quite possibly have been distorted by the report of von Staden. While the tragic events in Ivan’s youth and young adult life could certainly have done some mental damage, most of his actions seem rational to strengthen the state, but more importantly, his own safety.

Did the actions Ivan take accidentally strengthen the state, or was it a conscious action to protect Muscovy?

The Influence of Religion on Russian Culture

As we have seen multiple times throughout the readings, the influence of the Church was able to penetrate nearly every aspect of Russian life. Popular culture was definitely not immune to the domination that the Church had. The strict social hierarchy that included the high social classes and the Church were very prevalent in Russian society, they were essentially in control of what would be passed down generation to generation. Since most of the literate population was somehow involved with the Church, their damnation towards minstrels and their performances led to very little historical record of them, and what remained is never very positive.

The minstrels mostly entertained local villagers, who held their performances in the highest regard. “Surviving village inventories from around the year 1500 list minstrels just as they might some priest or smith, indicating not only a tolerance for such entertainers, but also a recognition of their social station and value.” (Kaiser 131) However, since the Church disapproved of them and their, “bawdy songs”, and how they “caricatured the world around them.” (Kaiser 128) Therefore, the Church was able to end the passing down of performances since they controlled a majority of the literate population. In some cases, princes would seek to have minstrels banned, in order to preserve their social order. (Kaiser 132) Minstrels did have an effect both on the lives of the average person and they upset the elite culture.

When observing the will of Patrikei Stroev, the presence of the Church and fear of God is evident immediately. He not only begins his will with a prayer, but he also gave a village and three beehives to the Church. Meanwhile, he gives his descendants animals or money. (Kaiser 130)

The paintings of Rublev are very similar to the paintings that would have been found in Italy during the Renaissance due to their religious nature. Art was a market that was driven by the patron, and often times, the artist themselves were deeply religious. (Kaiser 142)

Was pop culture truly representative of the people living during that time? Or is it purely whitewashed by the Church?

Works Cited

Kaiser, Daniel H. and Gary Marker. Reinterpreting Russian History: Readings, 860-1860s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994

Mongol Influence on Rus’ Culture

The Mongol occupation of the Rus’ lands is recounted by many historians as being incredibly detrimental to the culture of Rus’. The Mongols stormed into Rus’, manipulated the princes, and seized the opportunity to assert their military and political dominance upon Rus’. However, they did not force their shamanistic religion upon the Rus’ people, and they gave the Orthodox Church free reign. This interesting balance between the political and religious spheres and how they overlapped would eventually give the Rus’ people reason to believe that there was something they had to unite. The initial destruction of Rus’ culture by the Mongol occupation was brought back by the Church and the economic success that was in part due to the Mongols.

The historian A. M. Sakharov argues that the Mongol occupation destroyed early Rus’ culture in writing, architecture, crafts, and art and it, “failed to introduce any cultural innovations in their place.” (Kaiser and Marker 137) The Mongols exiled craftsman and architects which resulted in the loss of techniques that were passed down for generations. The loss of all the books which were stored in the Kremlin cathedrals by the invasion of Tokhtamysh is just one example of the large amounts of history destroyed. Sakharov does write on the rise of culture during what he refers to as the “Second Stage” of the Mongol occupation. (139) The economic success in cities such as Tver and Moscow meant Novgorod was no longer the only center of culture in Rus’. The rise of a Russian identity which was cultivated by the Church gave the people even more inspiration to push culture further forward.

However, Halperin later argues that the influence of the Mongols was more beneficial than many historians give credit. (105) The pride of Rus’ people as well as the dominance of the Orthodox Church who controlled most of the writing could easily have prevented the recording of the positives of the Mongol reign. While the Mongols did grant the Church immunity, the Church regarded them as infidels for their beliefs in shamanism and Islam. The rerouting of the fur trade by the Mongols led to the rise of Moscow and the cultural growth that occurred there during the mid 14th-mid 15th centuries had a very large positive impact on Rus’ culture. (106)

As the Primary Chronicles have shown multiple times, the religion of the subject being written about has a considerable consequence on how they are portrayed. While the recordings from the Chronicles describe the Mongol occupation as being only detrimental to Rus’ culture, it is possible that the Mongols had a positive influence on some of the culture.

What made the Mongols decide to initially destroy the Rus’ culture and then leave the Church to help bring it back?

How did the Mongol occupation unite Rus’ people together? Was it cultural unity that was finally discovered or just a desire to get rid of the Mongol yoke?

Works Cited

Kaiser, Daniel H. and Gary Marker. Reinterpreting Russian History: Readings, 860-1860s. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994