Category: Uncategorized Page 1 of 4

Few battles of the American Civil War provide a better illustration of the importance of topography and geography in a military campaign than the Chattanooga Campaign. The topography of the area surrounding Chattanooga, and the Confederate occupation of the high ground on Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge allowed the Confederate forces to hold General Rosecran’s Army of the Cumberland hostage, strangling their ability to resupply. From their position on the high ground, the Confederates could effectively cut off most of the supply roots available to the Union Army, allowing them to slowly starve Rosecran’s forces.[1] However, the benefit offered by the high ground had its weaknesses. The terrain prevented the confederates on the ridge from having a clear line of sight, and dips in elevation along the slope provided ample opportunities for Union troops to seek cover from Confederate cannon and musket fire.

The Chattanooga area also provided significant strategic advantages for the Union forces pushing into the South. While Major General Grant subscribed to Lincoln’s strategic preference for fighting to defeat armies rather than capturing cities, he understood that some geographic locations provided particular strategic advantage to the Union war effort. Chattanooga was the hub of four railroad lines: The Nashville and Chattanooga, Memphis and Charleston, Western Atlantic, and the Chattanooga and Cleveland Railroads.[2] Chattanooga was the “Gateway to the Lower South” and was strategically critical to a Union push into the Deep South.[3] The permanent capture of Chattanooga, secured by the Union victory after Missionary Ridge, set the stage for Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign the following spring. Chattanooga served as a base of operations and a center of the Union supply chain for Sherman’s campaigns through the end of the war.

This map seeks to provide a narrative of the Chattanooga Campaign and of the Battle of Missionary Ridge in particular for a general audience. The map follows the significant events in the campaign, beginning with the battle of Chickamauga, a noteworthy confederate victory. Confederate General Braxton Bragg was able to chase the Union Army into Chattanooga and besieged the town.[4] In order to better understand the physical features of the battlefield, the map is topographical, showing changes in elevation and other physical features such as waterways. Note that the confederate forces were concentrated almost entirely in areas of higher elevation. These strategic decision may have given the Confederates a better vantage point, but it also made maneuvering off of the ridges more difficult. In a letter from an officer in a South Carolina volunteer regiment reporting casualties from the Battle of Missionary Ridge, he notes that “the peculiar positions occupied by a large portion of our Army on the high hills surrounding that place… caused our loss in prisoners to be particularly high.”[5] The map also highlight troop movements, with lines (blue for the Union and Red for the CSA) representing the travel of military units or generals.

The gains from the Union victory in the Chattanooga campaign went beyond simple military success. The resurgence of hope in the South spurred by Confederate victory at Chickamauga was dealt a considerable blow.[8] As Southern morale eroded, the north rejoiced. In addition to pointing out the relationship between topography and strategy, the map provides insight into a shift in Union strategy for the final phase of the war. Victory in the Chattanooga campaign helped propel Grant to command of all Union Armies in March 1864.[6] Grant had built his reputation as a fighting general with his victories at Forts Henry and Donelson and at Vicksburg. Unlike most of Lincoln’s most high ranking generals in command, Grant, and other distinguished Western theater generals like Sherman and Sheridan, were willing to take risks and enact Lincoln’s strategy. Grant”s Overland Campaign proved his willingness to try to capture armies rather than cities, seeking the endgame that previous commanders like McClellan and Meade had been slow to pursue. The war intensified in 1864, as Sherman made his way toward Atlanta and later on to Savannah in his famous march to the sea.[7] While 1964 saw significant human costs, the strategic gains of the 1864 campaigns brought the war toward its close. Missionary Ridge opened up new strategic possibilities to the Union by making Sherman’s expedition through the Deep South feasible.

Primary Sources

“CHARGING MISSIONARY RIDGE.” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Oct 06, 1902.

“FEDERALS, NOVEMBER 25, 1863 STORMING MISSIONARY RIDGE, WON A VICTORY WITHOUT ORDERS.” The Washington Post (1877-1922), Nov 29, 1914.

“GEN. GRANT’S OFFICIAL REPORT OF THE BATTLES OF CHATTANOOGA, LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN AND MISSIONARY RIDGE.” The Charleston Mercury (1840-1865), May 11, 1864.

Gordon, John Brown. Reminiscences of the Civil War. n.p.: Baton Rouge : Louisiana State University Press, 1993., 205, 209–210.

“THE BATTLE OF MISSIONARY RIDGE.” New York Times (1857-1922), Dec 03, 1863.

Thomas O’Brien and Oliver Diefendorf, General Order 337, October 16, 1863. General Orders of the War Department, Volume II., (New York: Derby and Miller: 1864), 557.

Jenkins, Micah. Report No. 73 January 13th 1863. The War of the Rebellion (OR) eries 1, Vol. XLIII, (Part 1), p. 0523 [Ohio]

Footnotes

[1] “GEN. GRANT’S OFFICIAL REPORT OF THE BATTLES OF CHATTANOOGA, LOOKOUT MOUNTAIN AND MISSIONARY RIDGE.” The Charleston Mercury (1840-1865), May 11, 1864.

[2] Edwin C. Bearss, Fields of Honor (Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, 2006) 251.

[3] Louis P. Masur, The Civil War: A Concise History (New York : Oxford University Press, 2011.) 60.

[4] Weymouth T. Jordan., and John D. Chapla, “‘O what A turbill affair’: Alexander W. Reynolds and His North Carolina-Virginia Brigade at Missionary Ridge, Tennessee, November 25, 1863,” The North Carolina Historical Review, (2000): 320.

[5] J.F. Pressley, “SOUTH CAROLINA CASUALTIES AT MISSIONARY RIDGE.” The Charleston Mercury (1840-1865), Dec 08, 1863.

[6] Louis P. Masur, The Civil War: A Concise History (New York : Oxford University Press, 2011.) 64.

[7] Louis P. Masur, The Civil War: A Concise History (New York : Oxford University Press, 2011.) 74.

[8] Louis P. Masur, The Civil War: A Concise History (New York : Oxford University Press, 2011.) 60.

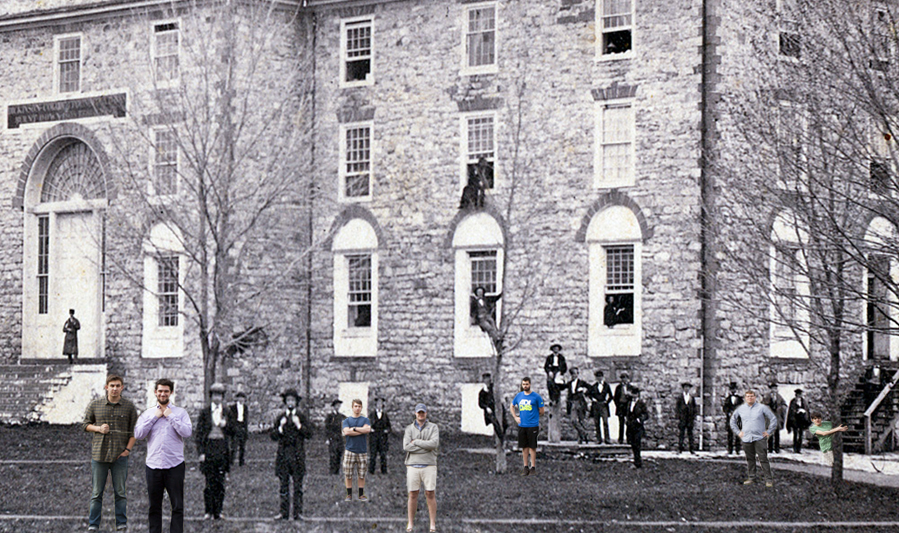

According to the College Archivist, this may well be the very first preserved photograph of Dickinson College –at least the earliest one that can be accurately dated.

There are several early photographs of West College (above) and East College that have been loosely attributed to the 1860s, but this striking image of Dickinson students standing in front of Old West most definitely comes to us straight out of the secession crisis from early 1861. We can identify the date of this image with some precision as being either in February or March of that year, because of a few tell-tale clues. First, the circular window near the crest of the front roof contains damage from a snowball fight that had occurred in December 1860.

There are several early photographs of West College (above) and East College that have been loosely attributed to the 1860s, but this striking image of Dickinson students standing in front of Old West most definitely comes to us straight out of the secession crisis from early 1861. We can identify the date of this image with some precision as being either in February or March of that year, because of a few tell-tale clues. First, the circular window near the crest of the front roof contains damage from a snowball fight that had occurred in December 1860.

It was then College Librarian and noted historian Charles Coleman Sellers who first observed this detail when he wrote a note thanking the family of William Henry Zimmerman (Class of 1861) after they had donated the photograph to the college in the 1950s. At the time, Sellers concluded this detail “probably” suggested a composition sometime in spring 1861, “since broken panes in the attic window indicate that the snowball damage of the previous season has not yet been repaired.”

Yet Sellers was surely being too cautious. The state of foliage on the trees (mostly bare, but with some early buds), coupled with the various types of colder weather dress by the students, makes February or March 1861 the obvious timing for the photograph. In other words, this should be considered an iconic image capturing a group of nearly two dozen young men, about half northern and half southern in their origins, right in the middle of the nation’s secession crisis and just before the outbreak of the Civil War in April 1861.

- Early spring foliage

- Cold Weather Dress

- Young Wide Awake

- Seated in Window

- Iconic pose

- Iconic pose

If only we knew more about some of the individuals depicted here. Relying on high resolution digital files, we can do a great deal with magnification, but the sad truth is that we cannot really get enough detail from this image to figure out exactly who was who in the photograph. We suspect most, if not all of them, were member’s of Zimmerman’s class. Yet part of the problem is that there are only a handful of images from the members of the Class of 1861 currently available to us, and most of those, like the image of Zimmerman, show the former Dickinson students in their later years.

- William Henry Zimmerman

- Charles Gere

- Henry Gregg

Thomas Jefferson McCants

But there is one intriguing possibility. One of the youngest images we have is of South Carolina native, Thomas Jefferson McCants, who graduated with the Class of 1861, and who has also been described in both contemporary letters and even historical fiction. McCants was one of the few southerners who tried to remain on campus in April 1861 as the war broke out. We know this because fellow Southerner William P. Willey (Class of 1862) described the chaotic scene in two remarkable letters he sent home to his father, a Virginia politician who opposed secession. There was also a later novel written about this period in Carlisle by the daughter of Herman Johnson, the college president. Mary Johnson Dillon’s In Old Bellaire (1906) contains a memorable character named Rex McAllister, a dashing student from South Carolina, who was reportedly based upon McCants. The novel describes McAllister (McCants) as being “slender,” favoring a “long coat, of finest broadcloth,” with “Bryonic collar,” and a “broad palmetto hat.” In her fictionalized account, Dillon also offers vivid depictions of McAllister’s “coal-black curls” and “smoothly shaven face.” All of this leads us to speculate that McCants may have been this figure in the 1861 photograph of Old West:

Or is it possible that McCants was also part of this photograph (below) taken from that era in front of East College with Mary Johnson (Dillon), seated front and center, along with several other unidentified younger men and women? Local reporter Joseph Cress recently featured a story about Dillon, her novel, and McCants’s role in a piece for the Carlisle Sentinel.

We might never know for sure. But we will certainly keep looking and will keep trying to find ways to bring the history of Dickinson College and the Civil War era to life in ways that can engage students today.

Mash up with modern-day Dickinson students, March 2016 (Credit: Ryan Burke)

Watch this video below to see how Dickinson students like members of the Class of 1861 reacted after the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861:

The New York Times “Disunion” series actually has several terrific and readable pieces on Civil War photography and art. Students in History 288 received assignments for just three of them. But each raises important issues about the impact of photography on the war effort. In addition to those pieces, students might appreciate this primer from the Civil War Trust on the process of period photography.

The New York Times “Disunion” series actually has several terrific and readable pieces on Civil War photography and art. Students in History 288 received assignments for just three of them. But each raises important issues about the impact of photography on the war effort. In addition to those pieces, students might appreciate this primer from the Civil War Trust on the process of period photography.

Abraham Lincoln was not trained as a military man. He once joked that as a young Illinois militia officer during the Black Hawk War, the only “live, fighting” enemies that he had attacked were mosquitoes. Yet, he was a remarkably self-confident commander-in-chief. Students in History 288 should be able to identify reasons for Lincoln’s self-assurance after reading articles about his wartime leadership from James McPherson and Brooks Simpson. As a test case involving their theories and other ideas about Lincoln’s wartime success, we will also conduct a close reading of Lincoln’s famous letter to Union General Joseph Hooker in January 1863.

Due by March 11, 2016

Objective

Students are required to create a custom-made Google map that helps document a Civil War battle using first-hand testimony and then to describe this map in a short (1,000 word) blog post.

Details and Guidance

- Students should be able to create at least ten (10) custom placemarks that help explain the main battle narrative. On the left column of the map, the placemarks should be arranged in rough chronological order. On the map itself, these markers should be situated in correct geographical position and should include text and images.

- Students should use quoted text from participants, found either in primary or secondary sources. Students should aspire to include comments from both Union and Confederate participants and from civilians as well. The best primary sources for this type of assignment include the OR, historical newspaper databases, and digitized or published collections of primary sources (such as letters, diaries or recollections). Keep quoted excerpts short, about 250 words or less.

- All text excerpts should be supported by relevant public domain images. The best source for such images include: House Divided research engine, Library of Congress, National Archives and Wikipedia. Make sure to include an image credit for every image.

- Here is a suggestion for how to best format the place marks:

Image credit: Firing on Fort Sumter (Courtesy of House Divided Project at Dickinson College) // From Louis Masur: “On April 12 at 4:30 in the morning, the first mortar shell exploded. On April 13, at 2:30 in the afternoon, [Major Robert] Anderson surrendered the garrison. No one was killed during the bombardment. Confederate secretary of state Robert Toombs had warned against this action, predicting ‘it will lose us every friend at the north.'” // Louis Masur, The Civil War: A Concise History, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 24

- Students should embed their maps along with a descriptive blog essay (about 1,000 words) based on properly cited secondary source research and including a clickable bibliography of primary sources by Friday, March 11, 2016 at noon.

- For help with footnote and bibliography format, please consult the following resources: The model post with bibliography examples, or this handout on Chicago-style footnotes, this short document from the history methods center, or this longer guide available from the library.

- Late maps will be penalized 5 points per day. Students will be judged by breadth of research effort, quality of prose and effectiveness of map design. The best maps will be published at The Dickinson Survey of American History.

Built in 2011 for the House Divided Project by undergraduate Brenna McKelvey, this map details the cavalry movements of Confederate General JEB Stuart during the Gettysburg campaign in 1863. Stuart’s absence at the beginning of the battle (July 1-3,1863) was one of the keys to the Union victory. Brenna used a trio of secondary sources for her map, including books by Emory Thomas, Jeffrey Wert, and Eric Wittenberg (Class of 1983).[1] Underneath this model, students in History 288 will also find a sample primary source bibliography to use as an example in their own work during spring 2016.

Primary Sources

Longstreet, James. Report No. 430, July 27, 1863. The War of the Rebellion (OR), Series 1, Vol. 27, (Part 2), p. 357 [MoA/Cornell]

Wilson, Theodore C. “Gen. Lee’s Farewell to My Maryland.” New York Herald, July 18, 1863 [Civil War Era / Proquest]

Footnotes

[1] Emory M. Thomas, Bold Dragoon: The Life of J.E.B. Stuart (New York: Harper & Row, 1986); Jeffry D. Wert, Cavalryman of the Lost Cause (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008); and Eric J. Wittenberg and J. David Petruzzi, Plenty of Blame to Go Around: Jeb Stuart’s Controversial Ride to Gettysburg (New York: Savas Beatie, 2006).

Dred Scott might be the most famous slave in American history. In Battle Cry of Freedom, James McPherson certainly spends a significant amount of time analyzing the eleven-year-long freedom suit which culminated in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857). Yet McPherson focuses on the legal battle at stake in the Supreme Court and pivotal role played by Chief Justice Roger Taney (Class of 1795). Students in History 288 should first consider what they might want to know about Dred Scott as a person. McPherson briefly describes the origins of Scott’s case but does not provide much in the way of biographical detail, nor does he describe Scott’s family. Yet it was probably Harriet Robinson Scott who propelled the freedom suits forward on April 6, 1846, a fact only recently highlighted in the scholarship largely because of the work of University of Iowa law professor Lea VanderVelde. VanderVelde’s fascinating biography, Mrs. Dred Scott: A Life on Slavery’s Frontier (Oxford, 2009) came out only three years ago, although an article upon which the book was based (also titled, “Mrs. Dred Scott’) did appear in the Yale Law Journal in January 1997 (now available through Lexis-Nexis). There is no comparable biography of Dred Scott, but Walter Ehrlich’s book, They Have No Rights: Dred Scott’s Struggle for Freedom (Greenwood, 1979) is widely cited as the best study of the case’s origins in Missouri and the most detailed account of the plaintiff’s personal story (available in Dickinson Library). Yet the principal source on the federal case remains Don E. Fehrenbacher’s The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (Oxford, 1978), a landmark study which won the Pulitzer Prize, but is not currently available at the Dickinson Library (nor available in any significant way at Google Books). For a good visual summary of the case and some helpful context on the under-appreciated role of Harriet Scott in the legal proceedings, see this online exhibit created by the Gilder Lehrman Institute with help from the House Divided Project and made available by the Google Cultural Institute.

In this video close reading, Prof. Pinsker argues that an under-appreciated turning point of the Civil War occurred on Tuesday, August 23, 1864. That was not the date of a battle, but rather of a unique political decision. President Lincoln wrote a secret memorandum on that morning which he presented sight unseen to his cabinet officers for their signatures. The short document outlined Lincoln’s plans in the event of what he termed the “exceedingly probable” outcome of the 1864 elections –his defeat. The so-called “Blind Memorandum” has subsequently entered into Lincoln lore as a sign-post of the gloom surrounding his administration in the summer of 1864. However, there are other ways to see this fascinating and complex document. Watch the video and decide for yourself what seems the best explanation for Lincoln’s motivation. What was he really trying to accomplish by writing the Blind Memorandum?

The Blind Memorandum: Abraham Lincoln and Leadership from The Gilder Lehrman Institute on Vimeo.

Here are an assortment of handouts distributed during the summer 2015 Underground Railroad seminar sponsored by the Gilder Lehrman Institute:

Gateway Stories

Slavery Law & Resistance

Crisis of 1850s

War and Memory