Five states had already ratified the Constitution before Massachusetts debated the matter in January 1788. In what became precedent in the ratifying conventions of the major states like Virginia and New York, ratification would only come with the Federalist concession that future amendments to the Constitution would be recommended and eventually adopted. With the endorsement of John Hancock, Massachusetts most influential politician, and his proposed nine future amendments, the state was the 6th to ratify. Virginia became the 10th state to ratify after similar debates and the proposal of future amendments that would eventually influence the first ten amendments to the Constitution.

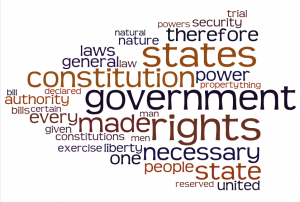

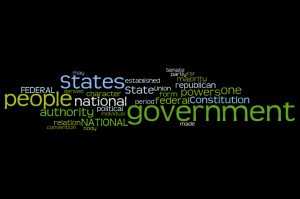

The state of New York featured staunch support for the Antifederalist cause but also contained arguably the biggest supporter of the Constitution and strong centralized government, Alexander Hamilton. In Federalist No. 84, Hamilton argued against the need to include a bill of rights in the Constitution. According to Hamilton, the Constitution already contained provisions that secured the rights of the people noting such clauses as the establishment of the writ of habeas corpus and the prohibition of ex-facto laws and titles of nobility which he affirmed were “greater securities of liberty and republicanism” than any bill of rights could profess. (Hamilton 84) An inclusion of a bill of rights Hamilton felt was not only unnecessary but dangerous. If certain liberties were specified unrestricted, what would come of the liberties unmentioned? Why mention that certain liberties can’t be restricted when these restrictions were never imposed? These were questions that Hamilton proposed in his argument that he underlined by stating, “the people surrender nothing, and as the retain every thing they have no need of particular reservations.” (Hamilton 84) The cloud alludes that the words government, constitution, rights and states are prominently featured throughout the essay highlighting that the central debate between adding these amendments was about securing the rights of the people but even more so deferring as much power away from the central government to the states as possible.

This debate can be confirmed by careful analysis of Antifederalist No. 84, presumably written by Robert Yates who argued for the inclusion of a bill of rights in the Constitution. In his direct rebuttal, Yates utilized metaphors and explained that in any creation of government, certain natural liberties must be surrendered to assure that government establish and carry out laws but that there are certain rights that cannot be surrendered. Other rights Yates mentioned “are not necessary to be resigned in order to attain the end for which government is instituted; these therefore ought not to be given up.” (Yates 84) Yates remained unsure of whether the Constitution affirmed that everything which is not reserved is given or that everything not given is reserved. The fear that the central government would overpower the state governments was the main perturbation for Antifederalists. If any law authorized by the central governmental was to become supreme law of the land, Yates concluded that the state governments must be protected by the restriction of the central government with the establishment of a bill of rights. Both clouds highlight the same words signifying that the inclusion of a bill of rights in the Constitution was probably less an emphasis about securing rights for the people but more to protect and reassert the rights of the states.