Month: April 2022 (Page 2 of 8)

Unsurprisingly, it was extremely difficult to map out the locations that Marco Polo had traveled to on the medieval map. On the modern map, it is much easier to visualize the distance that Polo had traveled, but due to the lack of labeling, or at least its visibility that the online version of the map had, it was hard to determine the route of his journey, therefore I was only able to determine the general region of the Middle East.

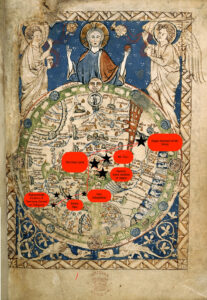

The Ebstorf Mappa Mundi goes into great depth of the mythological figures that were thought to be present in the world at the time, which contrasts the modern maps that are featured today. In seems to be that medieval maps, like that of the Ebstorf Mappa Mundi, were less fixated on accuracy, but more so a communication of culture, due to the lack of knowledge that the time had of the world. This goes along with the inclusion and focus on Christianity within the Ebstorf Mappa Mundi. Depicted in the medieval map is an image of Jesus embracing the world, with his head, hands, and feet, along with the inclusion of the Garden of Eden. The Ebstorf Mappa Mundi illustrates the key theme of religion that seem to reign during this time period, as the contents of the map are skewed in a Christian direction, as seen in having Jerusalem in the center of the map. There is no indication of any religious or political influence for the modern map, it simply consists of the geographic types of lands and the locations of countries, seas, etc.

I am very uncertain in the placement of the region in which I believe the Middle East is located, because even though the Ebstorf Mappa Mundi includes landmarks that were mentioned in Polo’s account, it was extremely difficult to read the tiny lettering of cities on the map, which is what I had to look for. I could only make out Sicily and India, and the general areas of Europe and Asia and Africa based on how T-O maps function. Since the Ebstorf Mappa Mundi is a T-O map, the direction and perspective is completely different to that of the modern day, as East is point towards the top, which helped in determining this. Due to the inaccuracies of the mappa mundi, it is hard to fully grasp the extreme distances that Polo traveled on this journey, which places less importance on the strife that he and other travelers had to deal with.

Finally, as previously mentioned, the Ebstorf Mappa Mundi, does a great job in illustrating culture, especially that of European origins, since it displays myths, landmarks, and religious inclusions that could assist individuals, like Marco Polo, in grasping the significance of certain locations and historical understandings to a specific region and community of people. The Ebstorf Mappa Mundi also assisted in sharing certain narratives about place and people within the world, since it had the ability to make judgements, such as dog-headed people living in a certain area, which caused these narratives to proliferate and thrive within the communities in Europe, but also reach other areas in the world.

Ayas (Yumurtalik), Ezrincan, Mosul, Baghdad, Tabriz, Kala Atashparastan (Kashan), Kerman, Hormuz, Kuh-banan, Mulehet (Alamut).

Unsurprisingly, plotting the journey of Benjamin of Tudela on both a modern and medieval map shines a light on many differences in the way that we view the world as opposed to Benjamin of Tudela.

The first glaring fact when it comes to the visualization on the medieval map is the scope. When looking on a modern map, his travels are impressive, even if one removes the places that he likely did not get to. The Tabula Rogeriana, on the other hand, makes his reported journey stretch from one end of the world to the other (not literally, for it was common knowledge for hundreds and hundreds of years that the world was round). From “Tutila” to “al-Sin”, the particular distortions of this map make it seem that Benjamin of Tudela had passed through a majority of the world’s lands. This is in addition to the fact that the points that are plotted in this map are not representative of his entire itinerary, so there are even more lands that he wrote he had passed through.

There are three major distortions that seem to cause the scope of Benjamin of Tudela’s journey to grow. The first is that Europe is enlarged, and Asia and Africa are diminished, making the lands that he wrote about in more detail (because he actually went to these places) appear more significant than the lands that he spent less time in. The second is the absence of the Americas for obvious reasons. The third is the many distortions made to the southern hemisphere. There is land in these areas, but the shape of almost anything south of Arabia is entirely unrecognizable and seemingly much less dense in terms of geographical features and settlements. This creates the impression that that there isn’t much of import to explore in that part of the world, and the viewer values more the lands that Benjamin’s journeys were meant to have taken place.

While the broad scope of his journey appears more impressive, some of the distances between particular locations seem more reasonable on the medieval map than on the modern. The locations marked in red on the modern map indicate places that Benjamin of Tudela likely did not travel to, and the decision of whether or not it was likely he went to a particular location was made mostly based off the fact that the routes that he would have had to take were highly erratic and nonsensical.

There are two main reasons why this is not quite the case on the medieval map. First off, some of the locations that he wrote about were not featured on the Tabula Rogeriana, particularly Rudbar and Amedia. These locations’ absence make it plausible that contemporaries could have believed that Rudbar and Amedia were on the route from Susa to Hamadan, making Benjamin of Tudela believe he could pass off actually going through those locations. This theory would further exemplify that Benjamin of Tudela did not really travel to these places, and that common knowledge was that Rudbar and Amedia were inland towns betwen Susa and Hamadan.

The second reason is that land distortions make routes that are actually irrational appear more reasonable. A significant example of this is the distance between Hamadan and Samarkand. On the Tabula Rogeriana, it visually appears to be about the same distance as that between Hamadan and Aleppo (Haleb). In reality, the direct distance between Hamadan and Aleppo is roughly 650 km, while the distance from Hamadan to Samarkand is over 1000 km. At this point, Benjamin of Tudela had traveled well over 1000 km, but in his itinerary there is shockingly little information about the lands between these two places. In the text, it appears as if the journey between Hamadan and Samarkand is no big deal, while in reality it makes absolutely no sense how he could have gotten that far east given the textual evidence to work off of.