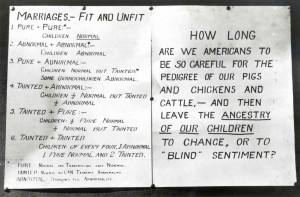

I found this image very interesting as it presents a chart of all the possible “blood” combinations imaginable.

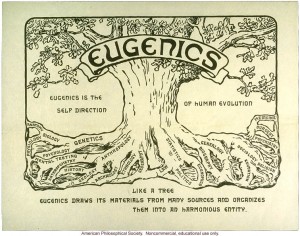

According to the eugenicists, each person belonged to a very specific racial category, one that completely determined every aspect of their life, from intelligence to physical appearance. As we can tell from the bottom picture, the eugenicists perceived themselves as humanists, advocating the best policies for the development of human civilization, even while advising states to adopt the most horrific and invasive social policies, ranging from sterilization to laws forbidding interracial marriage. Most tragic of all, these eugenicists never appear to doubt the goodness of their cause. As we saw in the article on eugenics and class, while they saw how some might confuse their agenda with that of the Nazis, they remained incapable of questioning their own motives and logic. As in the poster featuring the tree, the writing of eugenicists abounds with positive imagery of strength, health, and social harmony, reflecting a deep-seated fear of anything filthy or foreign.

I decided to include a poster made by American advocates of eugenics in order to better illustrate the nefarious aims of eugenicist groups. We now take it for granted that Americans can marry whomever they choose, regardless of their background. This poster’s denigration of “blind sentiment” stands in complete contradiction to this extremely important component of American society, and challenges the typically American idea that anyone can move beyond their roots, if they so choose. Looking at this poster, we see that the reactionary mentalities nurturing fascism did not remain confined to Europe, but contaminated the entire world. Perhaps the use of the word ‘contaminated’ obscures the true character of eugenics and its fascistic outlook. Could they stem from some inherent human nature we must seek to overcome?