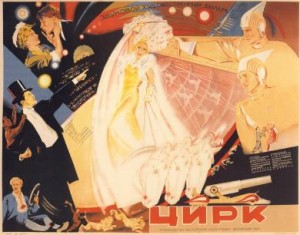

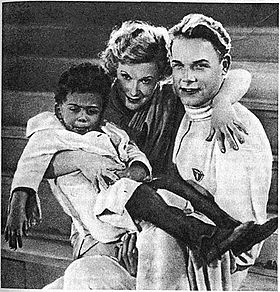

The 1936 Russian Soviet film, Circus, directed by Grigori Aleksandrov and Isidor Simkov, tells the story of a famous American performer, Marion Dixon, as she flees from the United States after persecution from giving birth to a black child. She goes with a corrupt theatrical agent, Franz von Kneishitz, who looks suspiciously like Adolf Hitler, to Russia where she becomes a circus performer. After falling in love with another performer, Ivan Petrovich Martinov, von Kneishitz becomes jealous and not only prevents her from staying with Petrovich, but actively abuses Marion, despite claiming to love her.

The comedy-musical film is vibrant and silly, but it has serious undertones that are reflected through the characters. Marion’s guilt and shame is clear on her face whenever she’s not on stage. When she’s performing, she puts on a face that she thinks will please the people around her. Marion is constantly worried about the truth of her child coming out that when she has to choose between staying at the circus with Petrovich and leaving with von Kneishitz or else have the truth revealed, she goes even though she will be miserable.

The climax of the film is a final scene when von Kneishitz reveals her child as a product of Marion being a “mistress of a Negro” to the audience of the circus. He calls it wrong and that she should be expelled from society, but the audience just responds with laughter as they take the child from him and pass the boy around to keep him from von Kneishits’ grasp. The director comes up to him and explains that all children are welcome in the Soviet Union, “whether they have white skin, black skin, or red skin.” This is a critique of American society and the racism that exists there, but not in the Soviet Union where race is unimportant. This ties in with our discussions on how soviets viewed nationality as important, but not race because it is a trait that cannot be changed. The final scene is also a blatant message of nationalism, where the people, among them Marion, Petrovich, and the black boy, are marching in a parade to celebrate the glory and equality of the Soviet Union.