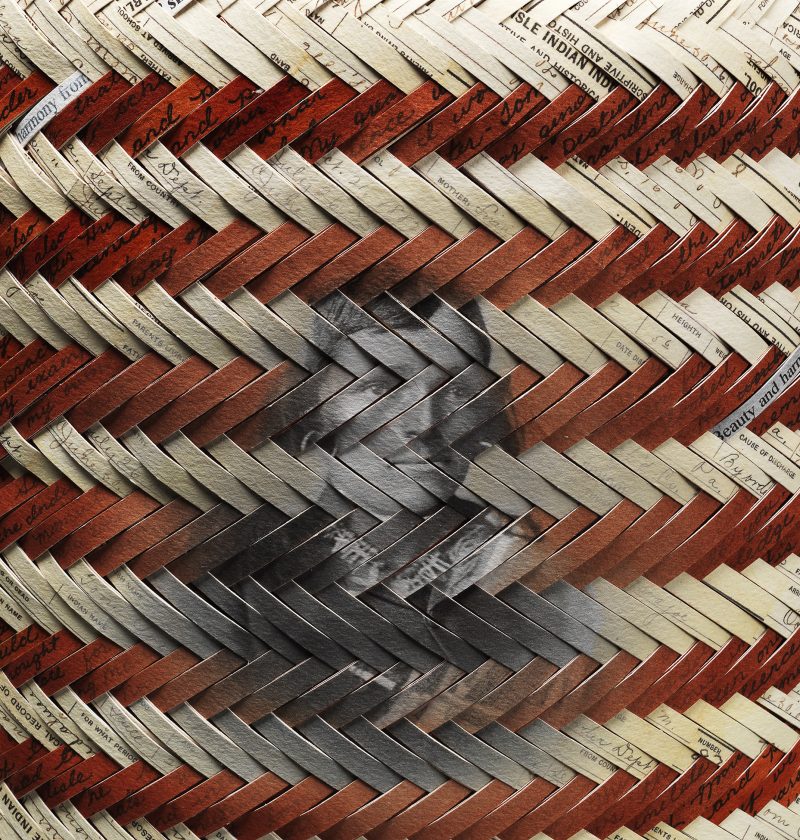

Look closely at this detail from a basket. Do you see one man or two woven together? Can you make out what looks maybe like words printed on some woven strips? Are you curious to learn more? Audiences who came to The Trout Gallery last year to see this and other baskets by Eastern Band Cherokee artist Shan Goshorn sure were. I’ve worked at The Trout Gallery for about six years now, and I have to admit I’d never seen our visitors so intent on figuring out what they were looking at.

Form and content. Form and content. A carefully-planned relationship between these two things lies at the center of just about every really great work of art. In fact, it’s sort of the tenet of Art History 101 that you can’t truly understand a work of art until you have this relationship pretty well sorted out. In this story, I’d like to share with you my experience of how a seemingly simple choice, the medium of a work of art, transformed how people responded to its content.

This basket, Two Views, features a photograph of Carlisle Indian School student Tom Torlino. The basket is woven together using a traditional Cherokee weaving technique, but the material is not traditional–it is paper. And printed on this paper are words, colors, and two photographs of Tom Torlino, one taken when he first arrived at Carlisle Indian School and another after he’d been at the school for some time. Goshorn played with different weaves to create the image that appears on the final basket. Depending on how the strands are woven, Tom’s appearance changes in subtle ways. Here is the study Goshorn made while she was preparing to make this basket (this study hasn’t been professionally photographed yet, so thanks to our Collection Manager James Bowman for snapping it for me during one of his regular Corona vault-checks):

Achival ink, acrylic paint, and artificial sinew on Arches watercolor paper

15 x 10.5 in., 2018,

2019.7

Gift of the artist, Shan Goshorn, to Philip Earenfight.

The basket presents a composite image of Tom, merging his pre-and-post-assimilation appearances (featured in the two roundels under the woven strips above) into one. The Carlisle Indian School, like many off-reservation boarding schools of its time, offered a curriculum that was built around the goal of assimilating Native Americans into white settler society. Many, if not most, of the students who attended these schools were forced to enroll due to unfair and harsh U.S. policies towards Native Americans. Goshorn’s own mother, grandmother, and adopted mother attended these boarding schools, and she has witnessed first-hand the damaging effects of these schools to Native American culture. Thus, issues of identity, cultural assimilation, and the lasting impact of U.S. government initiatives towards Native Americans are ones that she has thought about and worked with in her art for for some time. However, she hasn’t always had such success in getting her audiences to view and truly sit with her artwork. She attributes this primarily to her choice of medium.

Goshorn was a photographer and printmaker early in her career. Long the medium of protest, printmaking is known for its graphic boldness and ability to communicate political messages. However, when Goshorn created prints and photographs that addressed the longterm impact of US government policies towards Native Americans, she found that people either turned away, seemingly grappling with complicated feelings of culpability and shame, or became angered, perceiving an accusation in the works. Neither of these reactions were Shan’s goal. She wanted audiences to look closely, to truly understand, and by doing so to participate actively in what she saw as a potentially larger process of healing the damage done by past atrocities.

This is precisely what happened when Shan created her first basket. In her visit to Carlisle, Goshorn talked about how the material form of a basket itself invites conversation and discovery. The medium makes it ideal for educating and encouraging discussion about a very difficult subject because it is associated with a utilitarian function, it’s content is deciphered in bit-size chunks, and these chunks are pieced together through a process of slow looking. Watching this process happen was the magic I experienced during our exhibition of Goshorn’s baskets. Audiences leaned in, they asked so many questions, and they worked in groups and teams to point out details in each basket that might help them to build a deeper understanding of its central theme and historical reference points.

In this close-up detail, one can see that the individual splints of Two Views feature words in addition to colors. As Trout audiences came together around this basket, many noticed that the words were printed in some cases, and written in cursive in others. They also picked out individual words and began to piece together aspects of Torlino’s life as they deciphered text. This is because the tan splints feature Tom Torlino’s official Carlisle Indian school records while the red splints feature handwritten stories about Tom’s life passed down through his Navajo family and told by his oldest son, Francis. There are also scattered white, black, blue and yellow splints woven throughout the basket; these colors are sacred within Navajo culture. Printed on these colored splints are a Navajo prayer for well-being. The basket features a traditional Cherokee double-weave in a pattern called Black-birds eye. As a whole, the basket presents a nuanced view of Tom, one that invites viewers to discover on their own the meaning of this object.

And this basket works because the medium matters. Its form is the ideal vehicle for developing in viewers a complex, and nuanced understanding of Tom Torlino’s life as it relates to both history and the present.