40 x 30 in. , 2009

2017.8. Purchased by Dickinson College Students as part of the Student Purchase Initiative.

Confined. Boxed in. Stuck. Trapped. These are some of the words that I hear friends use these days when they talk about home. Life in quarantine has dramatically shifted how many of us view the spaces we live in. In effect, our homes have become spaces of safety and protection and, by contrast, the spaces outside our home are associated with danger and risk. Somehow knowing this doesn’t seem to help when cabin fever sets in. This past week, as I was pondering how my relationship to our dining room (currently my home office) has shifted over the past couple of months (I step down into it from the kitchen and all the previous days of doing the exact same things in this space play before me in an endless loop; it’s sort of like déjà vu plus a heavy dose of fatigue), I couldn’t help but think of the work of Lalla Essaydi. She treats a completely different context than that of COVID-19 today, but I don’t think I’ve seen any artist more complexly interrogate the myriad relationships among physical space, culture, and psychological perception.

Lalla Essaydi came to campus during The Trout Gallery’s 2018 exhibition of her photographs (CATALOG LINK), and to hear her talk about her work is a powerful experience. Here is an excerpt from an interview in which she talks about space:

“Of particular interest to me is what my photographic work has taught me about the importance of architectural space in Islamic culture. As I indicated earlier, traditionally, the presence of men has defined public spaces: streets, meeting places, places of work. Women have been confined to private spaces, that is, to those of the home. And as I also suggested before, these physical thresholds define cultural ones. Confinement in actual spaces can be the result of transgressing metaphorical boundaries, of crossing into prohibited cultural spaces. Many Arab women today may feel the space of confinement primarily as a psychological one, but its origins lie, I think, in the architecture itself. The women in my photographs are both held with an actual space, and at the same time are confined to their “proper place,” a place of walls and boundaries, a space controlled by men. These women have become literal odalisques (“odalisque,” from the Turkish, means belonging to a place). One has only to look at the continuity between the henna on their bodies and the patterns of the surrounding tiles to see how they have become identified with their surroundings.”[1]

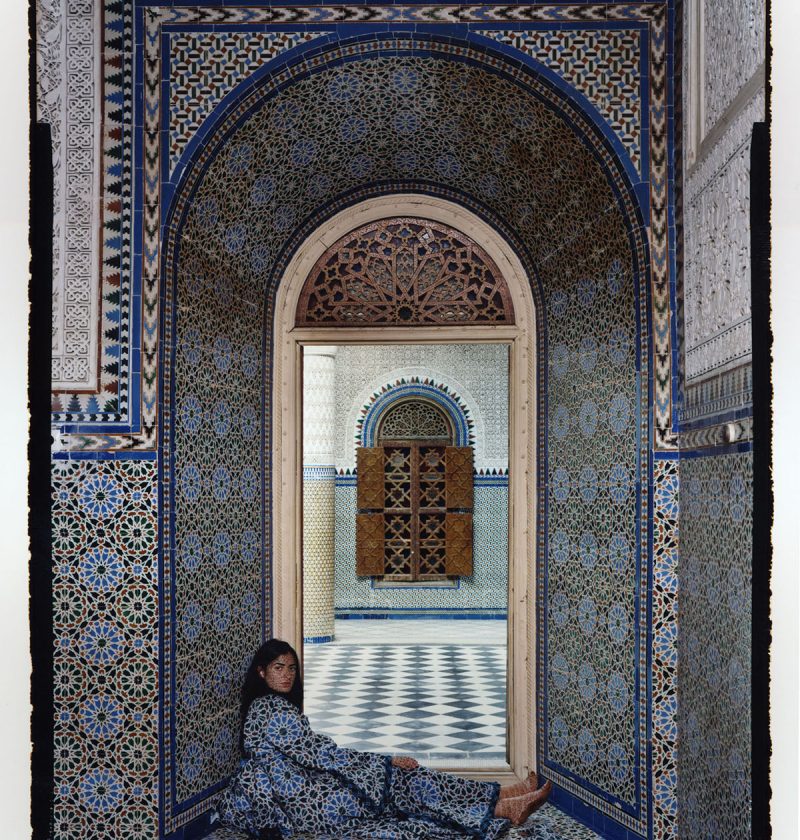

Essaydi’s work is based on her own experiences growing up in a harem in Morocco, studying art in France, raising a family is Saudi Arabia, and then coming to the United States as an artist. Islamic artistic traditions, specifically of architectural spaces, but also of textiles and calligraphy, play a crucial role in her consideration of the experiences of Arab women. She views her photographs as but the final step in a performance that begins with the conversations she has with her subjects about their personal lives. These conversations become poetic text that Essaydi applies onto the women’s bodies using henna, a female art form; the shape of the writing resembles traditional Islamic calligraphy, the kind typically associated with the Qur’an. As a child, Essaydi was not permitted to learn this type of calligraphy because she was a girl. The women are then draped with fabrics that Essaydi usually creates to match the patterns and colors of a chosen architectural space. In the image below, from The Trout Gallery collection, you can see the dress that Essaydi made to match the surrounding architecture and if you look in the bottom right corner you will see she even made shoes to match. At times these spaces hold personal meaning from Essaydi’s childhood, at other times they are manufactured spaces, created like sets for a theater performance. Finally, Essaydi photographs the women, at times directing the women and at other times shooting them in poses they request.

2017.8. Purchased by Dickinson College Students as part of the Student Purchase Initiative.

The photographs that result from these pieces of performance art are BEAUTIFUL. Like, the kind of beauty that draws disinterested tweens in through The Trout Gallery doors because they caught a glimpse while waiting for their music lessons in our building. In fact, the elaborate ornament and sensuous fabrics common in her photographs are so beautiful that it sometimes takes a while for viewers to process how tightly framed many of her images are. Essaydi’s female figures typically occupy shallow spaces, resplendent in an ornamental beauty that stops just short of obscuring the women at their center. The result is a visual push-pull that lies at the heart of a dialectic about space, how individuals perceive space, and how these experiences are grounded in realities socially constructed and physically felt.

Essaydi’s meditations on this dynamic are best experienced by viewing specific photographs. To experience a virtual tour of her works, follow along via our tour menu page HERE.

-Heather Flaherty

[1] Ray Waterhouse, Lalla Essaydi: An Interview, Journey of Contemporary African Art, August, 2008, pgs. 144-149.