The Logeion app. The University of Chicago, 2013. iTunes. Free.

Reviewed by Daniel Plekhov, Dickinson College (plekhovd@dickinson.edu)

The Logeion mobile application aims to provide a one-stop look up for Greek and Latin dictionary entries. Like its parent website, also developed at the University of Chicago, it collects and presents a wide range of valuable reference materials.

The Perseus Digital Library provided several lexica:

- Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon

- Liddell and Scott’s Intermediate Greek Lexicon

- Autenrieth’s Homeric Dictionary

- Slater’s Lexicon to Pindar

- Lewis and Short’s Latin-English Lexicon

- Lewis’ Elementary Latin Dictionary

Logeion gives entries from each of these on a single page under the relevant headwords, streamlining the process of looking up definitions. But it also adds to the corpus of digitized lexica. As of the latest update, new material accessible from the mobile application includes:

- The Diccionario Griego-Español Project (DGE), a brand new Greek dictionary

- DuCange’s massive dictionary of Medieval Latin

- Basiswoordenlijst Latijn (BWL), a Latin dictionary that include examples of Latin words in context, illustrating their most common uses.

LaNe, the Latin-Dutch dictionary accessible from the Logeion website, is not currently available from the mobile application. DuCange, the reference work for medieval and late Latin, while available on the mobile application, is not provided in its full-text version as on the Logeion website. Even so the Logeion app is an unparalleled resource for students of Greek and Latin, and serves a wide range of specializations within Classics. The ease and simplicity of its interface ensures that despite the daunting amount of material even beginning students of Classics will benefit. And crucially the mobile platform allows users to access all these fantastic resources without an internet connection.

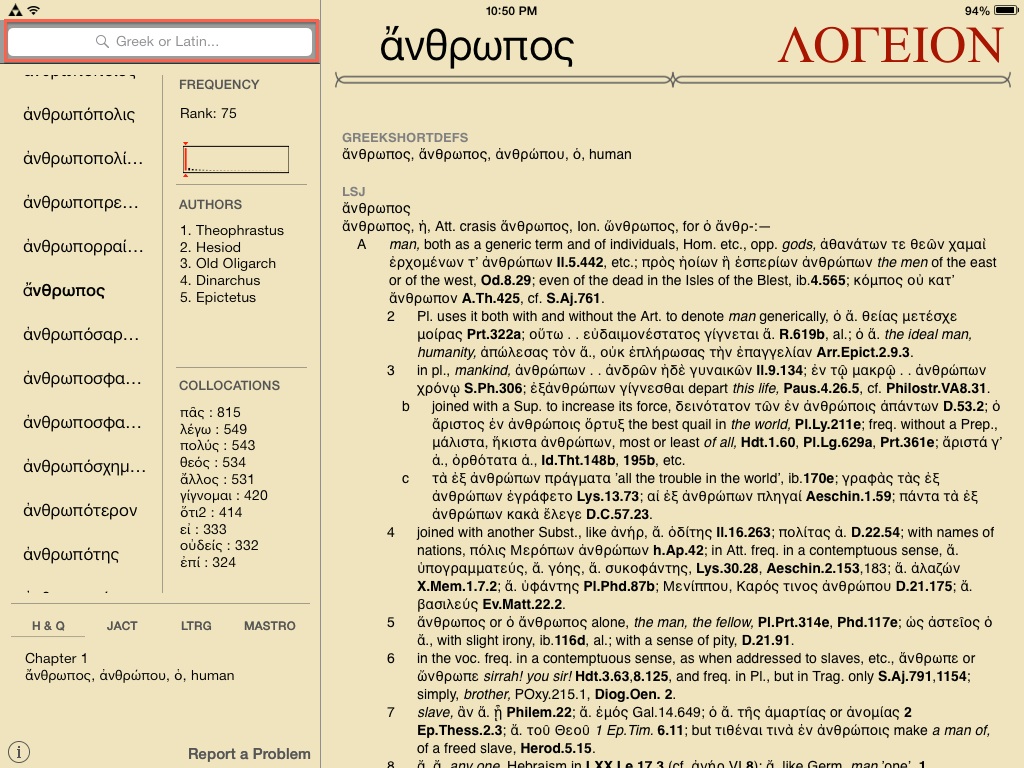

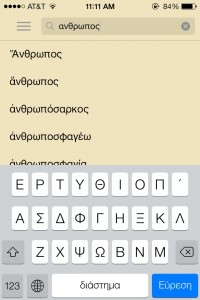

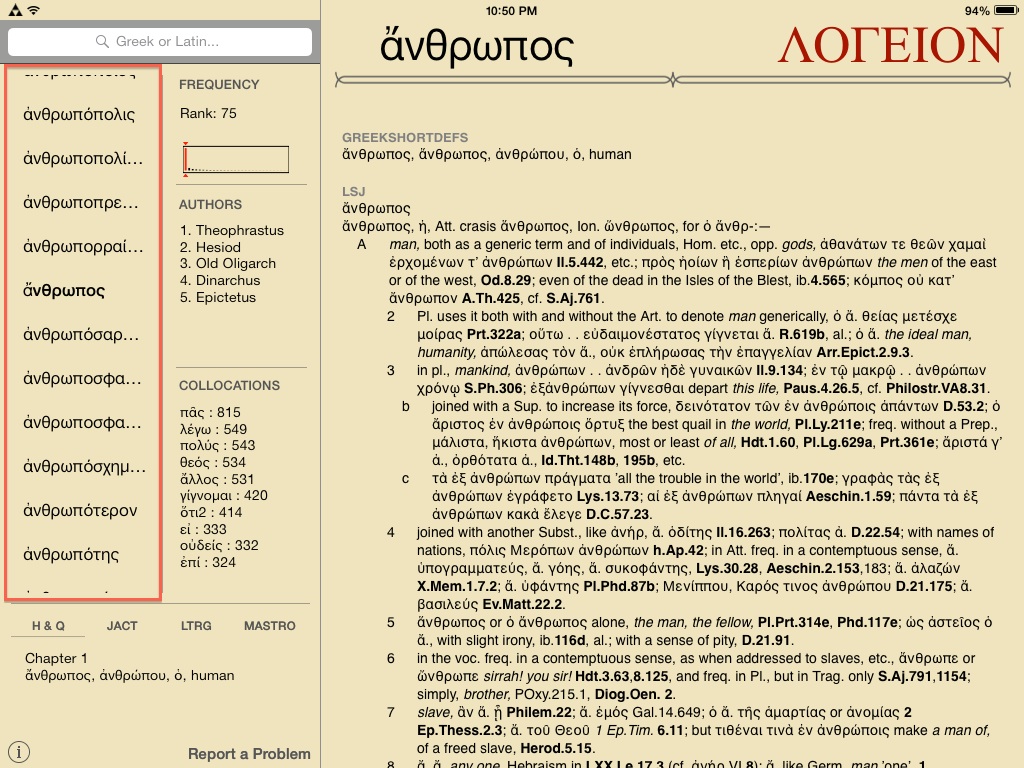

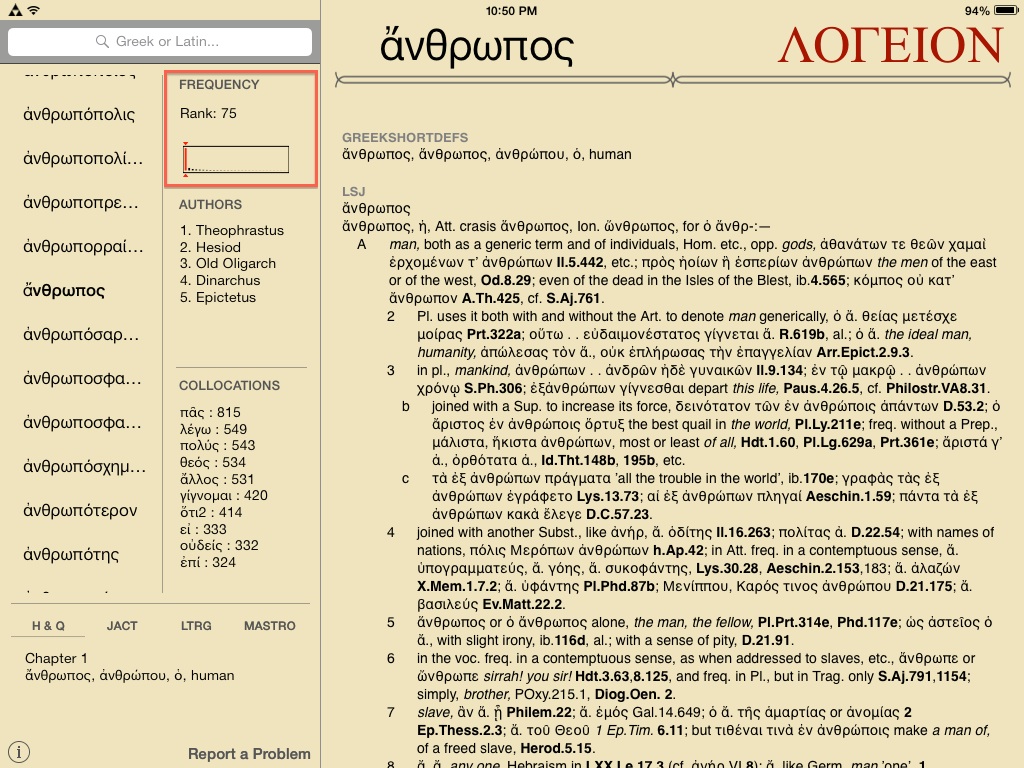

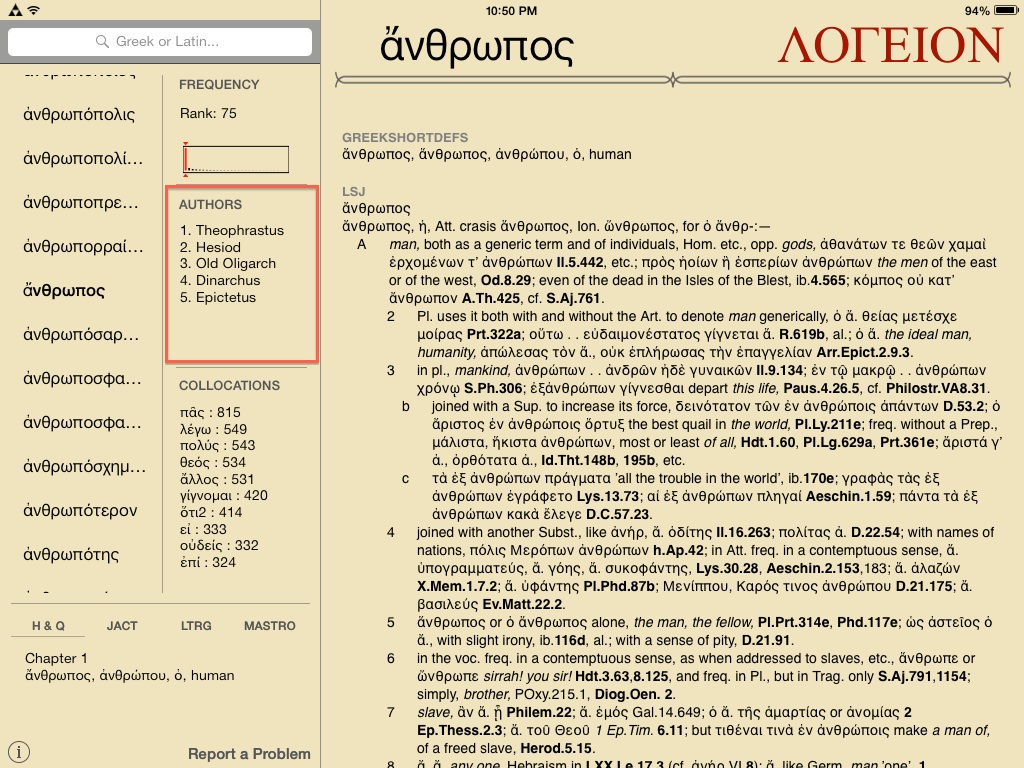

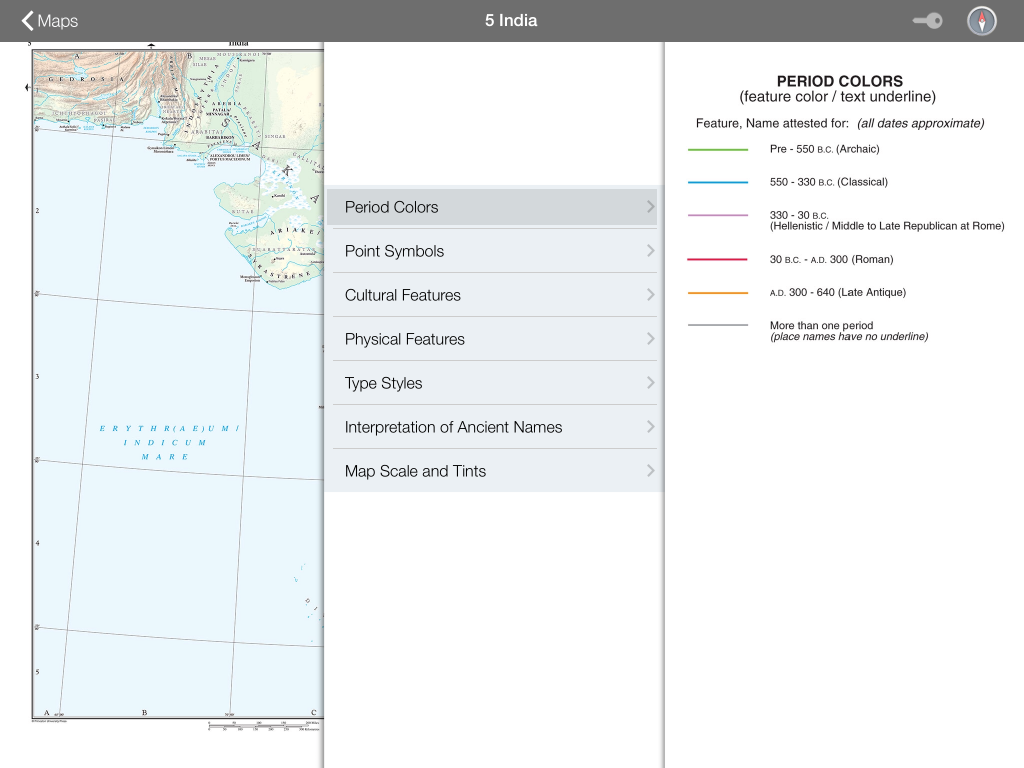

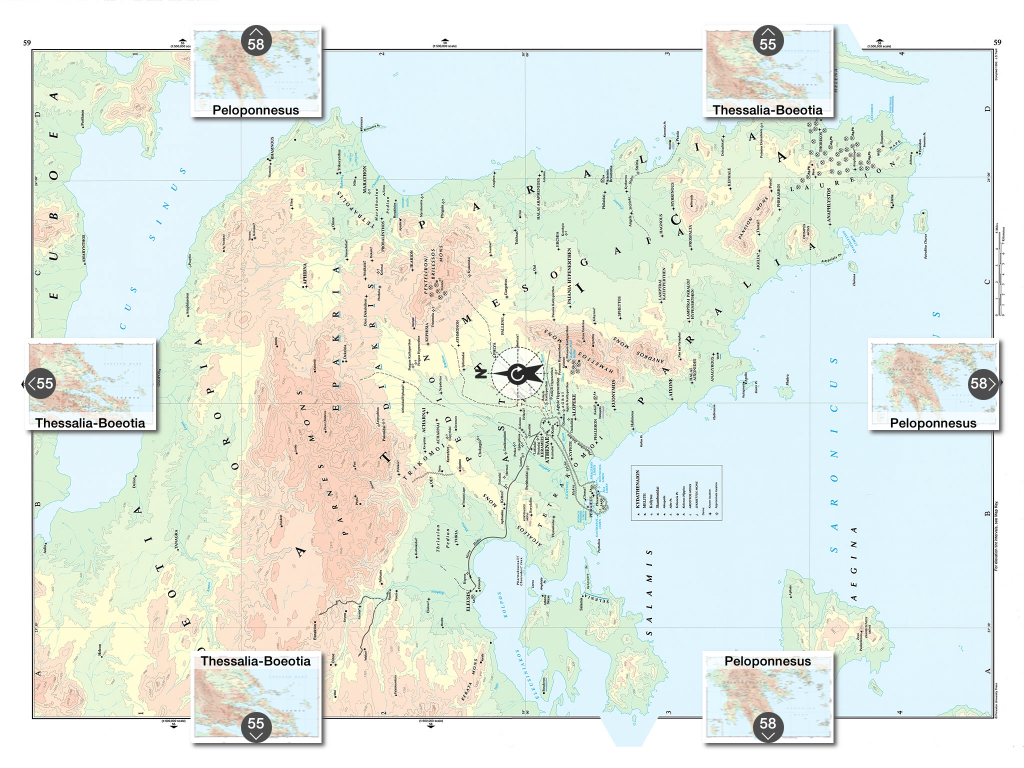

I tested this application on both an iPhone 4 (running iOS 7.0.4) and an iPad. The most important distinction between the two is that the iPhone application allows only for portrait view, while the iPad allows for both portrait and landscape. The landscape view is more attractive and efficient than the portrait view, as it allows the menu to be visible alongside the content. The iPhone also does not allow for the word wheel. In what follows I will discuss the application as experienced from the landscape view on an iPad.

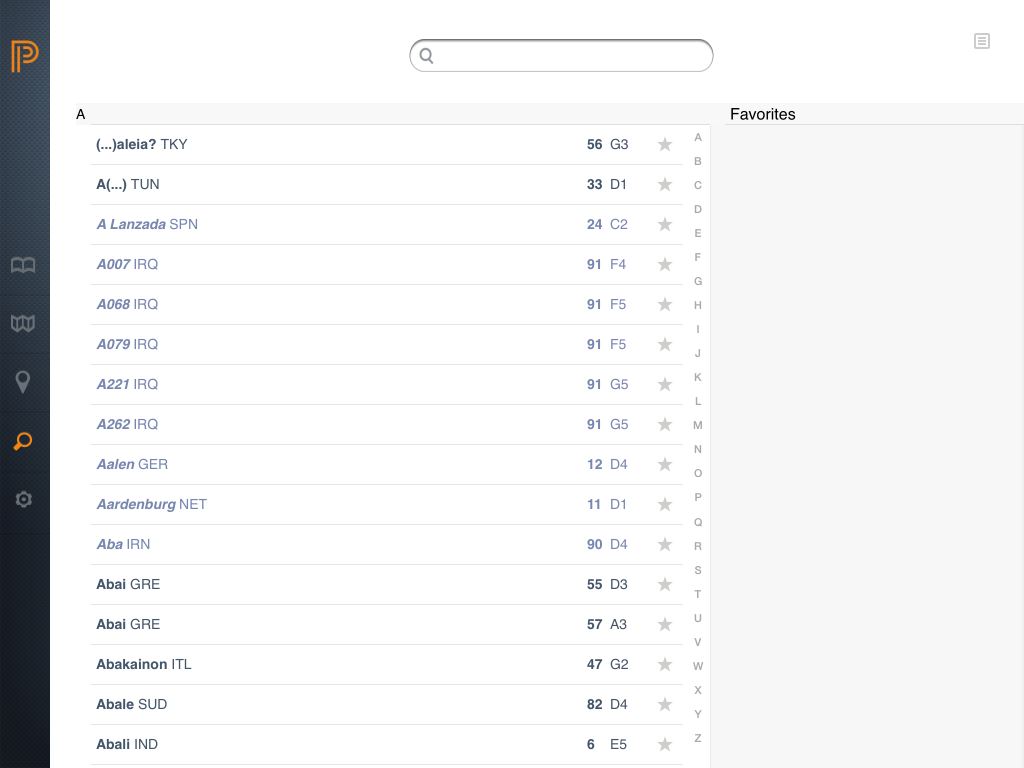

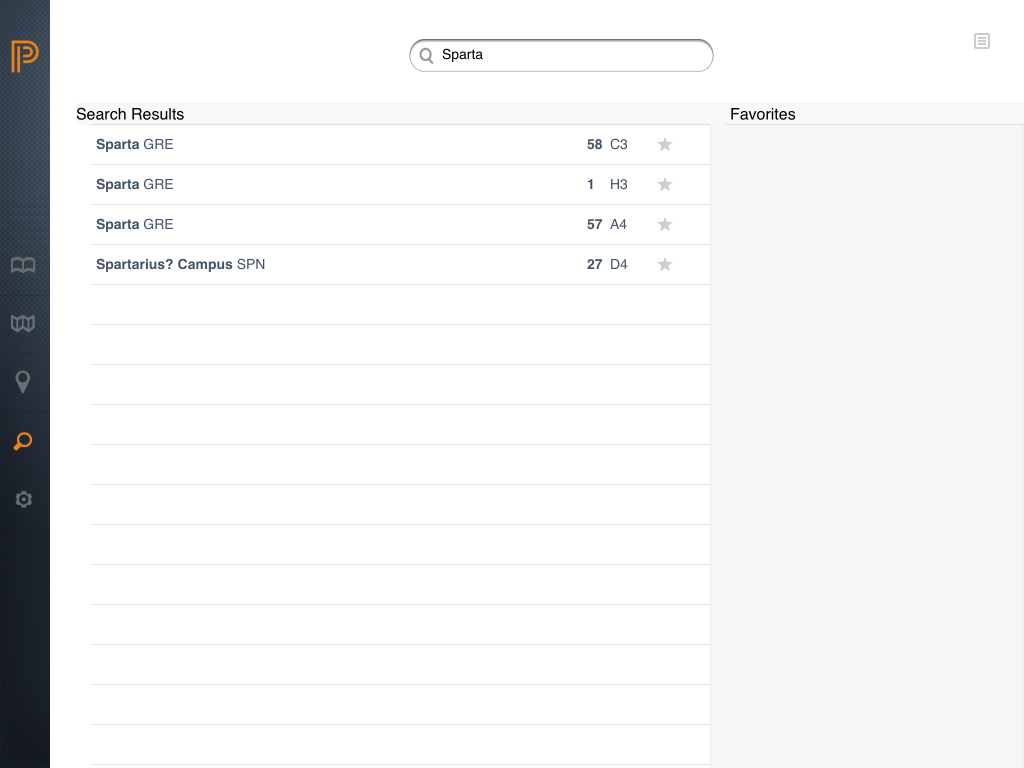

The Greek keyboard is easily enabled.On opening, the program defaults to an entry for the Latin word lux. At the top left is the search field. From here the user may type in words in Latin or Greek, using the Modern Greek keyboard, which must be enabled. Transliteration is not supported (as it is on the website), but enabling the Greek keyboard is easy, and the application has a help section with detailed instructions for doing so. Greek words may be typed in without accents, which would be difficult and tedious to type, especially on a mobile device. The word ἄνθρωπος had to be typed in fully, but other words are more quickly recognized by the application, which begins to provide results from the third letter.

Something that was at first confusing was that ἄνθρωπος was given twice, the first capitalized and the second not. Reading the help section explained this: proper nouns are included alongside nouns and verbs in the search results. Even so, it would be helpful if from these search results one could view some information about each result. As it is, clicking on any result immediately takes one to the full entry entry, and to get back to the previous results it is necessary to fully retype the search .

Once on the noun ἄνθρωπος, the menu on the left gives a scrollable word wheel of words alphabetically before and after ἄνθρωπος. The word wheel is not continuous and infinite, however, and to navigate to more than twenty words away you can scroll up the twentieth word and select that as the new entry, thus generating a new word wheel range. It would have been nice I think to have a full word wheel from which I could have scrolled as far as I needed. This may be more pertinent in cases where the search is for a very commonly used stem or verb from which derive many entries, such as νομίζω. Being able to continuously scroll through all the entries would be helpful in these cases.

Alongside the word wheel is further information about the entry. At the top is the frequency, ranked along a scale that groups words by their frequency across all texts, in increments of 150 words. A number is given as well as a red line, making it instantly and very clear how often the word is used.

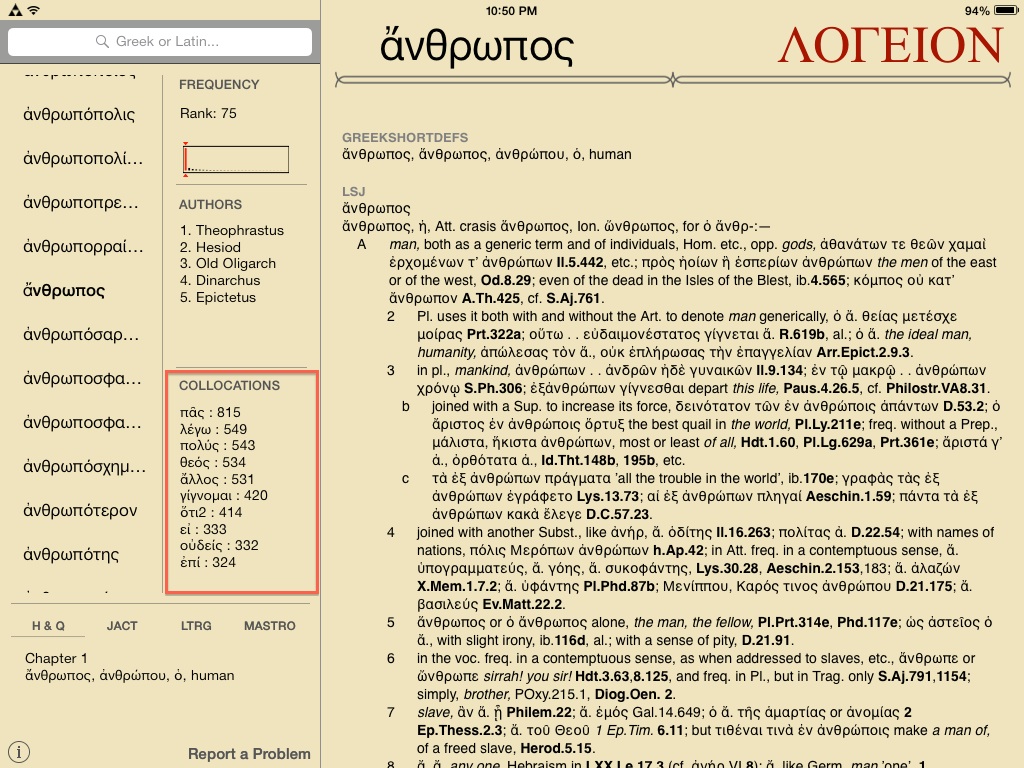

Below that is a list of authors in whose works this word appears. This is given in addition to the examples from the corpus which are included at the bottom of word entries, when available.

Below the list of authors is a list of collocations. This is a valuable piece of information to have apart from the dictionary entries. Collocations are often given within the dense block of text for each word entry, and having them separate allows for quick reference.

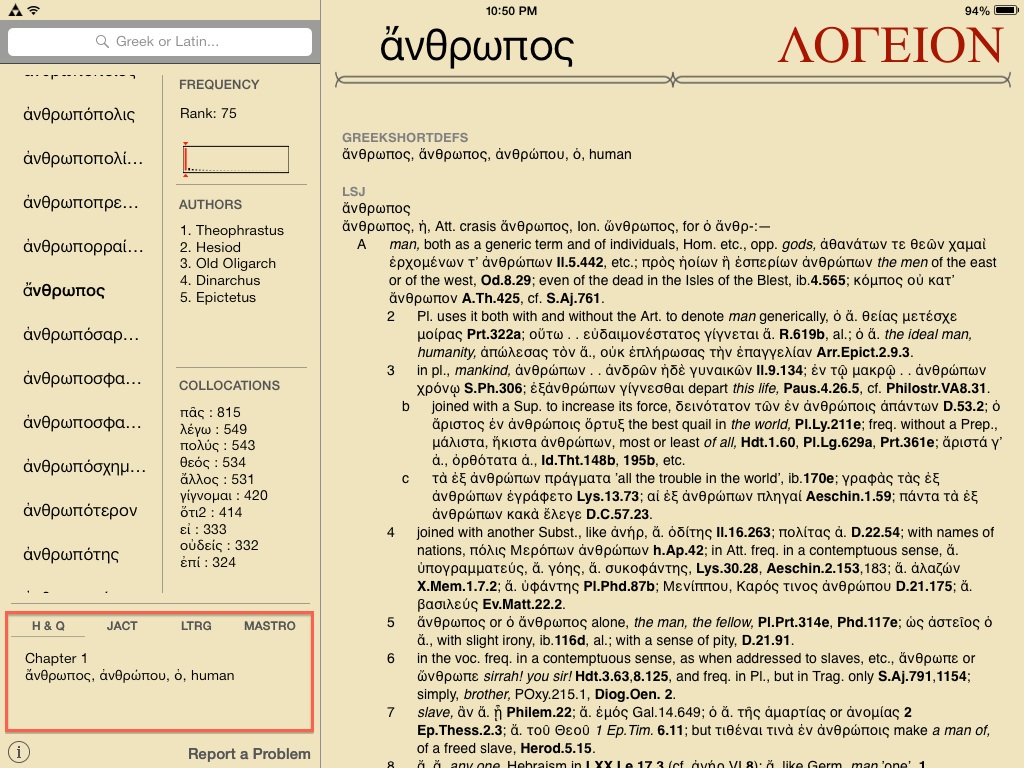

Below the word wheel and the additional information comes a list of introductory Greek or Latin textbooks in which the headword appears, if it happens to. At the time of this review, the textbooks referenced were:

- H & Q (Greek: An Intesive Course, by Hardy Hansen and Gerald M. Quinn)

- JACT (Reading Greek: Grammar and Exercises, by Joint Association of Classical Teachers)

- LTRG (Learn to Read Greek, by Andrew Keller and Stephanie Russel)

- LTRL (Learn to Read Latin, by Andrew Keller and Stephanie Russel)

- Mastro (Introduction to Attic Greek, by Donald Mastronarde)

- Wheelock (Wheelock’s Latin, by Frederic M. Wheelock and Richard A. Lafleur)

The user can easily navigate between textbooks simply by clicking on them, which will provide the entry in the textbook, as well as where it can be found.

In the bottom left corner is an information link that provides tips on how to use the application and explanation of its various functions.

Within the actual word entry, the first information given is always the “ShortDef,” which provides the most basic definition(s) of the headword. Following that is the entry for that word in all the available reference materials. At the end of the dictionary entries, examples from the corpus in which this word is used is also provided.

For anyone who has ever had to work with multiple dictionaries and texts open at the same time, being able to simply scroll and access so much information with the simple swipe of a finger from a single device is truly appreciated. I have no doubt that the application will continue to be added to, both in regards to content as well as usability.

Elements of the application that I would wish to be added is a way to bookmark certain entries, or perhaps create a favorites section for choice words. As it stands now, however, the Logeion mobile application represents a crowning achievement for the digital classics, and a tool that I envision having great use for students and educators alike.

–Daniel Plekhov