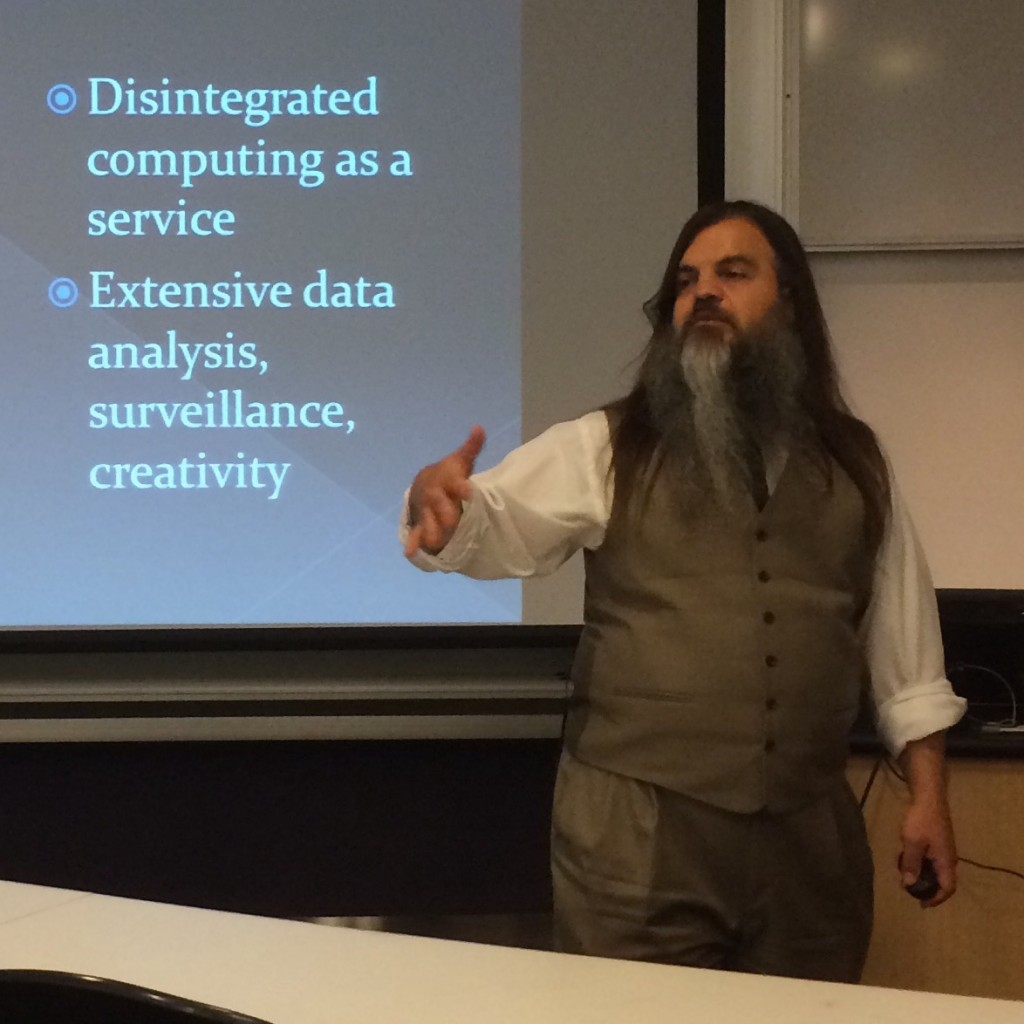

We are now five years past the period of the $700,000 grant from the Mellon Foundation that spurred a good amount of new digital humanities activity at Dickinson and strengthened existing projects. The Dickinson projects, it seems to me, are in various ways good examples of the pursuit of humanistic goals using digital means. They help put the humanities in Digital Humanities. DH, of course, means various things to different people, for example:

- the use of databases for literary analysis, distant reading, the computational humanities project of running computer programs on large corpora of literary texts to yield quantitative results which are then mapped, graphed, and tested for statistical significance

- natural language processing and machine translation

- online preservation and digital mapping

- data visualization and digital publishing

What most of these things have in common is the use of large datasets and computational methods to try to understand human cultural products. There has started to be a substantial backlash against this kind of work. To some, the phrase digital humanities may even appear a contradiction in terms. The digital values large data sets of often messy and imperfect information, speed, and countability. Humanistic ideals of exacting scholarship, searching debate, high-quality human expression, exploration of values, and historically informed critical thinking may seem incompatible. Nan Z. Da recently found a receptive audience when she surveyed computational approaches to literary texts and found them lacking.

When you throw social media in there, the digital seems like a positive threat to the humanistic. Jill Lepore speaks for many in her recent history of politics in the United States, These Truths, when she identifies a new, digitally enabled model of citizenship, “driven by the hyperindividualism of blogging, posting, and tweeting, artifacts of a new culture of narcissism, and by the hyperaggregation of the analysis of data, tools of a new authoritarianism.” She sees the Internet as having “exacerbated the political isolation of ordinary Americans while strengthening polarization on both the left and the right, automating identity politics, and contributing, at the same time, to a distant, vague, and impotent model of political engagement.” (p. 738) Digital media have taught us anew how to like and be liked, she points out, but also how to hate and be hated.

Despite these malign trends it is quite possible to pursue, promote, and defend the humanities in the new medium, and it is being done right here at Dickinson, in projects like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School Resource Center (Jim Gerencser and Susan Rose); Jim Hoefler’s “Caring During Serious Illness: Advice from Caregivers”; House Divided, the Civil War history site overseen by Matt Pinsker; and the project I direct, Dickinson College Commentaries.

Humanities goals include:

- historically informed critical thinking

- self-knowledge in line with prior understandings, the exploration of values

- the cultivating of powers of thought and expression, including civil and substantive debate

Historically informed critical thinking

Tens of thousands of young people from Indian communities all across America were sent to the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania between 1879-1918. What was the purpose, the strategy, the outcome? What can we learn from interrogating this historical, educational experiment about the goals of its founders, the students who were sent there, the impact on their families and communities, U.S. military and domestic policy related to Indian tribes, the history of American education, about race and ethnic relations? The CIIS site gives you the tools to do this, from massive troves of digitized documents and photographs, to teaching modules for various levels, including close reading modules that teach how to interpret documents and discuss them productively.

The House Divided Project aims to bring alive and explain the turbulent Civil War era in American history. Using Dickinson College as a both a window and a starting point, the House Divided Project hopes to find in the stories of thousands of individuals a way to help illustrate how the Civil War came, why it was fought so bitterly, and ultimately how the nation survived. The site provides thousands of documents, photos, and records of individuals to sift through, and provides guidance in the form of key themes such as Civil Liberties, the Dred Scott case, Ft. Sumter, the Gettysburg Campaign that link out to the records of places, people, documents, timelines, and images.

Self-knowledge in line with prior understandings

Most patients who live with serious illness (and their family members) will typically need to make a number of important decisions about the kinds of medical treatment that is provided in this time. Hoeffler’s Caring During Serious Illness site is devoted to providing patients and their loved ones with advice about these decisions, offered by Clinical Advisors whose unique perspectives derive from devoting their professional lives to caring for patients with serious illness. The site gives you interview excerpts from dozens of advisors from different medical specialties, different faith traditions, with the aim to help us care for aging relatives in a sensitive and kind way, and to give us ways of thinking about death, to help us understand it for ourselves. Rabbi Feinstein, for examples says, “Death the most frightening thing in life. The only thing that is more powerful than the fear of death is gratitude for the blessings of life.”

Cultivated powers of thought and expression

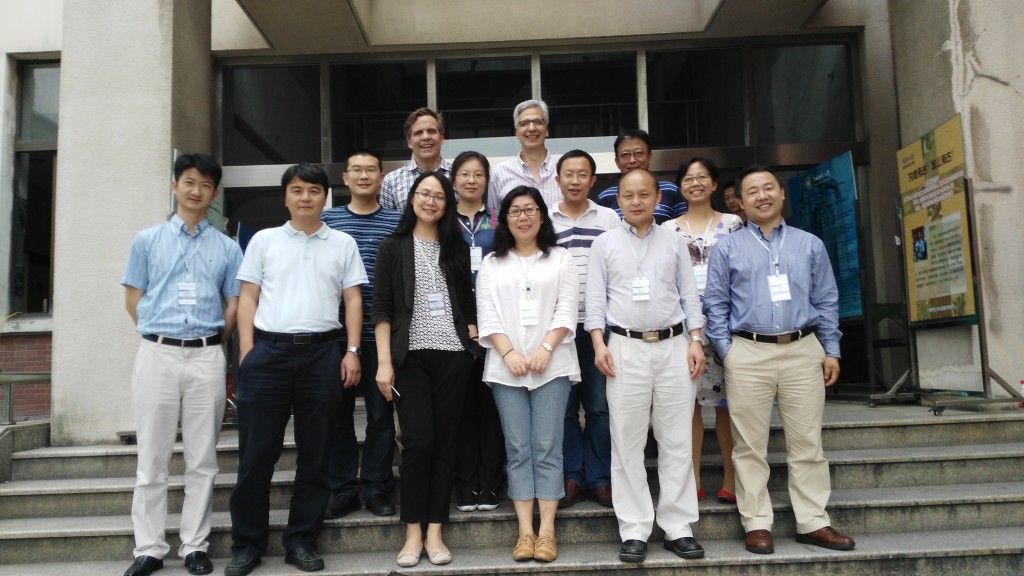

Dickinson College Commentaries presents commentary and annotation on classical texts that guide readers through understanding and appreciation. We try to model humanistic reading practices and to infuse good teaching into the site: not too much information, close reading, provide varying perspectives. The Chinese sister site Dickinson Classics Online focuses on intercultural understanding, with Chinese commentaries on Greco-Roman classical texts, and (soon) Latin and English commentaries on the Chinese classics.

Two areas are in my opinion being neglected by DH scholars, here and elsewhere: translation and podcasting. If you want humanities to be global, good translations are crucial. Literary translation on the open internet is abysmal, and this needs to change. Dialogue and debate are crucial to the humanities, and podcasting is absolutely golden opportunity to model humanistic dialogue and publicize humanities research. Edward Collins’ Kingdom, Empire and Plus Ultra: conversations on the history of Portugal and Spain, 1415-1898 is a great example.

The world needs historically informed critical thinking, high quality expression, and self-knowledge in line with prior understandings. The world needs the humanities. Our political system is in crisis for lack of a culture of democratic discussion. Social media seems to be doing everything it can to crush our capacity for understanding and dialogue. We have the digital tools to promote humanism. Dickinson is leading the way, and I am proud to be working among the scholars, librarians, and teachers who are creating these fine resources.