“Congressional hearings had already begun on the statute that would ultimately be known as the Smith Act. It was aimed, initially, at the fingerprinting and registration of aliens. By the time it passed, it had grown to become the first peacetime law against sedition in America since the eighteenth century. The Smith Act included the toughest federal restrictions on free speech in American history: it outlawed words and thoughts aimed at overthrowing the government, and it made membership in any organization with that intent a federal crime.” –Tim Weiner, Enemies, 83

Starting with its passing in 1940, the Smith Act became one of the most effective weapons in the government’s arsenal during its domestic war on communism. Proposed by conservative representative Howard Smith of Virginia and signed into law by Franklin Roosevelt, the act made illegal any act of advocacy, public or private, on behalf of overthrowing the government. This was a major blow to the Communist Party as it effectively made being a member illegal because of the Communist Manifesto’s emphasis on an eventual violent overthrow of modern capitalist regimes.

The act would not be brought fully into play until 1949 when most of the leaders of the Communist Party USA were brought before the Supreme Court for conspiracy. The trial

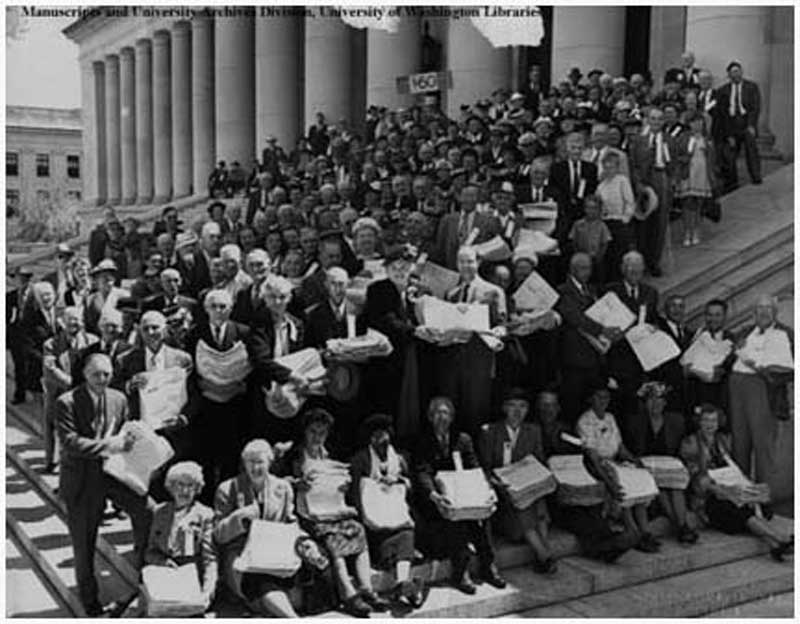

Here activists bring petitions to the Supreme Court in support of the 11 defendants of the "Smith Act Trial"

would become infamously know as the “Smith Act Trial.” The government’s case: the men and women on trial subscribe to communist ideology, one of whose tenets clearly advocates for a violent overthrow of the government. Therefore the defendants are guilty of conspiracy under the Smith Act.

Eugene Dennis rebutted the government’s stance in his opening defense to the Supreme Court. He said, “The allegation of crime rests on the charge that we Communist leaders used our inalienable American rights of free speech, press, and association, and sought to advance certain general political doctrines which the indictment falsely says teach and advocate the duty and necessity to overthrow the Government of the United States by force and violence.”[1] Despite the defense’s efforts to show how the Smith Act violates the first amendment, the court voted 6 to 2 to convict the eleven Communist Party leaders. In his dissenting opinion made in June of 1951, Justice Hugo Black wrote, “Public opinion being what it now is, few will protest the conviction of these Communist petitioners. There is hope, however, that in calmer times, when present pressures, passions, and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment Liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society.”[2]

This is a picture of the Supreme Court as it existed during the Smith Act Trial. First row, second from the left is Justice Hugo Black who disagreed with the 6 to 2 majority.

The Smith Act still remains on the books today. To make sure you are not in violation of it, you can read the text of the act here:

Whoever knowingly or willfully advocates, abets, advises, or teaches the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying the government of the United States or the government of any State, Territory, District or Possession thereof, or the government of any political subdivision therein, by force or violence, or by the assassination of any officer of any such government; or

Whoever, with intent to cause the overthrow or destruction of any such government, prints, publishes, edits, issues, circulates, sells, distributes, or publicly displays any written or printed matter advocating, advising, or teaching the duty, necessity, desirability, or propriety of overthrowing or destroying any government in the United States by force or violence, or attempts to do so; or

Whoever organizes or helps or attempts to organize any society, group, or assembly of persons who teach, advocate, or encourage the overthrow or destruction of any such government by force or violence; or becomes or is a member of, or affiliates with, any such society, group, or assembly of persons, knowing the purposes thereof–

Shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than twenty years, or both, and shall be ineligible for employment by the United States or any department or agency thereof, for the five years next following his conviction.

If two or more persons conspire to commit any offense named in this section, each shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than twenty years, or both, and shall be ineligible for employment by the United States or any department or agency thereof, for the five years next following his conviction.

As used in this section, the terms “organizes” and “organize”, with respect to any society, group, or assembly of persons, include the recruiting of new members, the forming of new units, and the regrouping or expansion of existing clubs, classes, and other units of such society, group, or assembly of persons.

(from http://www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/comm/free_speech/smithactof1940.html)

[1] Eugene Dennis, “Opening Statement of Behalf of the Communist Party.” March 21, 1949, From, Ellen Schrecker, editor. The Age of McCarthyism: A Brief History with Documents. New York: Bedford, 2002. Pp. 200.

[2] Justice Hugo Black, “Dissenting Opinion in Dennis et al. v. United States.” June 4, 1951. From, Ibid.