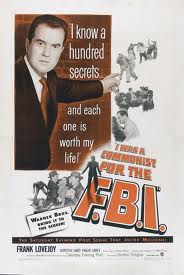

I Was a Communist for the FBI –Here is a link to a film clip from the 1951 film I Was a Communist for the FBI.

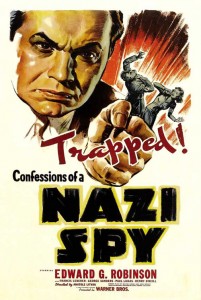

Any first hand account of J. Edgar Hoover would be flawed if it did not convey his obsession with the public’s opinion of himself and the FBI. This included pop culture. Many great books have been written about the FBI’s changing place within popular culture and media including, G-Men: Hoover’s FBI in American Popular Culture by Richard Powers, and The FBI and the Movies by Bob Herzberg.

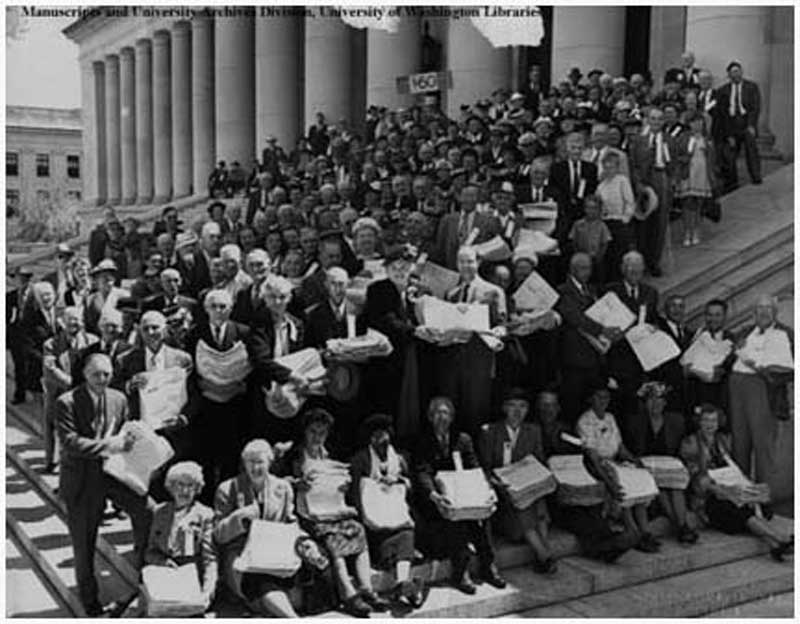

One of the more interesting occurrences in which the FBI’s clandestine operations melded with popular culture was the popularity of I Was a Communist for the FBI, which started as a serial story in the Saturday Evening Post. Both a film and a weekly radio drama of the same name soon followed. The fictionalized film, staring Frank Lovejoy, would even earn an Academy Award nomination for best documentary.

The man behind it was Matt Cvetic, a notoriously short and stout from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He had been unsuccessful in various government jobs until in 1941, after three rejections from U.S. Army Intelligence, he was accepted into the FBI under the pretense that

he was fluent in seven Baltic and Slavic languages, including Russian.[1]After he began his career with the FBI, Matt Cvetic became one of their most useful informants. For nine years Cvetic worked his way up the ranks of Pittsburg’s Communist Party becoming a well-trusted member of the community. Daniel Leab writes in his article on Cvetic, “The FBI no doubt

considered Cvetic an extremely useful informant for much of his tenure with the Bureau. Various Special-Agents-in-Charge of the Bureau’s Pittsburgh office reported to Hoover on Cvetic’s “excellent results.”[2] However, according to Cvetic, the job was starting to become to much for him.

Cvetic claimed in front of the HUAC that his family had begun to shun him because of his affiliation with the Communist Party. He also claimed to be under physiological and spiritual distress because his cover as a Communist had prohibited him from attending church lest he be exposed as a man a faith. For whatever reason, the stressful job seemed to be taking its toll on an already unstable man. From many accounts I’ve read about Cvetic, most accuse him of being an abusive father and husband as well as a raging alcoholic.

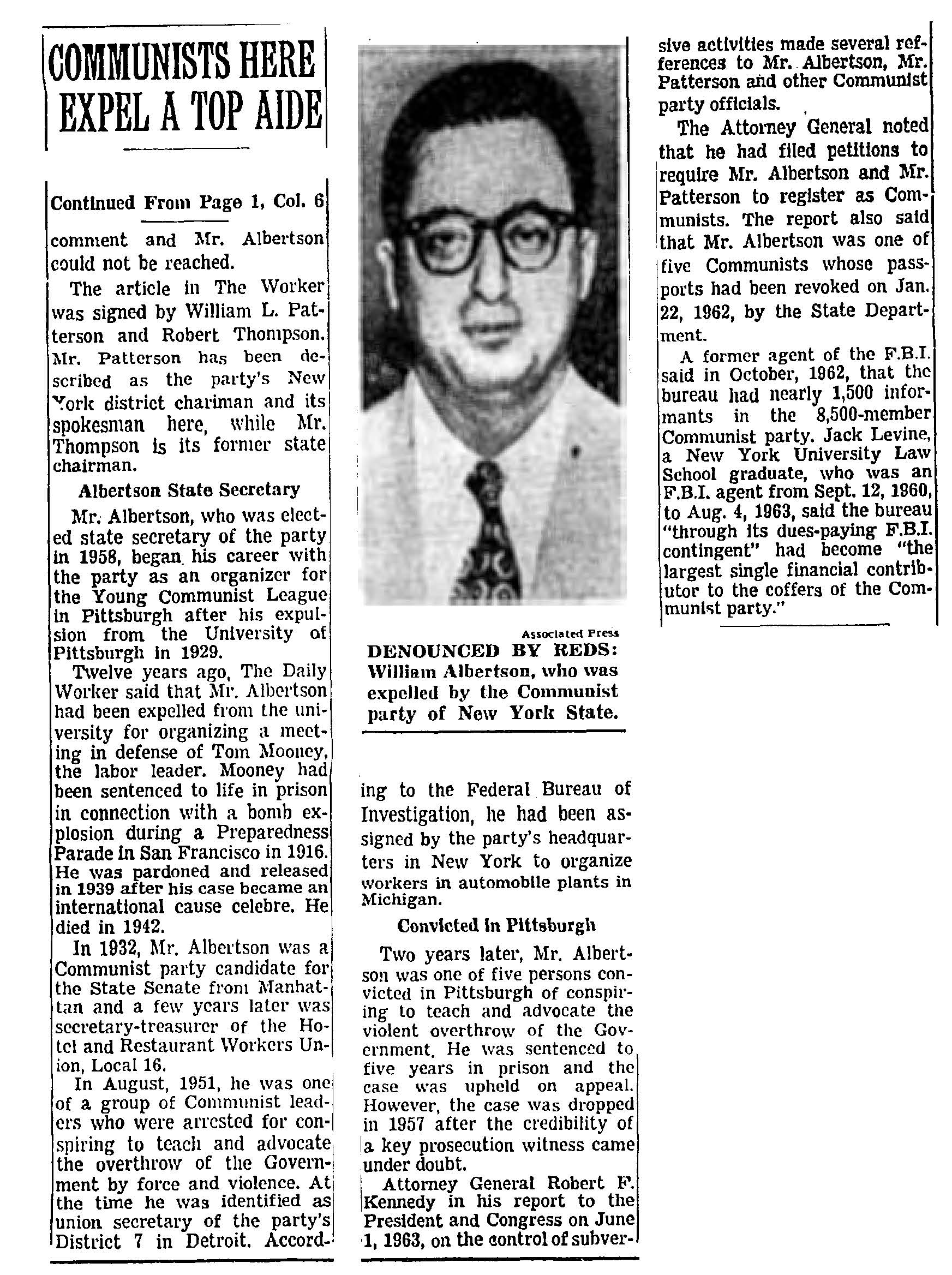

By the late 1940s, the FBI was beginning to sense that Cvetic might need to be let go. Due to his well-publicized testimonies in front of the HUAC (including testifying against William Albertson) his effectiveness as an informant was beginning to wane. The FBI was also concerned with his very overt extra-marital affairs. It was not uncommon for Cvetic, while drunk, to publicly brag about his covert exploits as a way to gain female attention.[3] It was in light of his deteriorating relationship with the FBI that Cvetic approached journalist James Moore as a way to cash in on his FBI exploits. Thus I Was a Communist for the FBI was born. It started as a regular story installment in issues of the Saturday Evening Post but was soon  picked up by Warner Brothers for a cinematic version. In the FBI files for the film, you can see that throughout the entire production process and after its nation-wide release, the FBI received innumerable amounts of letters of people trying to confirm whether or not the film was FBI sanctioned. The response from the FBI was always the same, “The FBI does not have any ties with Matt Cvetic and will not take any stance on the film.” (that can be read in the FBI vault here)

picked up by Warner Brothers for a cinematic version. In the FBI files for the film, you can see that throughout the entire production process and after its nation-wide release, the FBI received innumerable amounts of letters of people trying to confirm whether or not the film was FBI sanctioned. The response from the FBI was always the same, “The FBI does not have any ties with Matt Cvetic and will not take any stance on the film.” (that can be read in the FBI vault here)

The whole story of Matt Cvetic and I Was a Communist for the FBI shows the public fascination with FBI covert actions and the counter-communist initiatives of the U.S. government. It is also indicative of something I have discussed many times on this blog, that being the potency of the public paranoia that the FBI and its affiliates cultivated throughout the 1940s, 50s, and 60s.