“We had to change our tactics….We had to make every effort to develop live informants, utilize both mike and technical wiretaps, and become more sophisticated in our actual techniques.”- Jack Danahy, quoted in Enemies, 193.

If the FBI were watching you, would you know it? Would you see shadowy men standing outside your window? Would your phone mysteriously click every time you picked it up? I cannot try to imagine the type of paranoia that would have set itself into members of subversive organizations during the late 1940s and into the late 1950s. The worst part is that many of the people being watched during this time period knew it, and even if they did not know it for a fact, they suspected it. The paranoia pervades the memoirs of the time. It drove many of the famous leftists of the era, like writer Howard Fast or playwright Arthur Miller into the countryside and away from New York City where the FBI knew how to use the urban environment to their benefit.

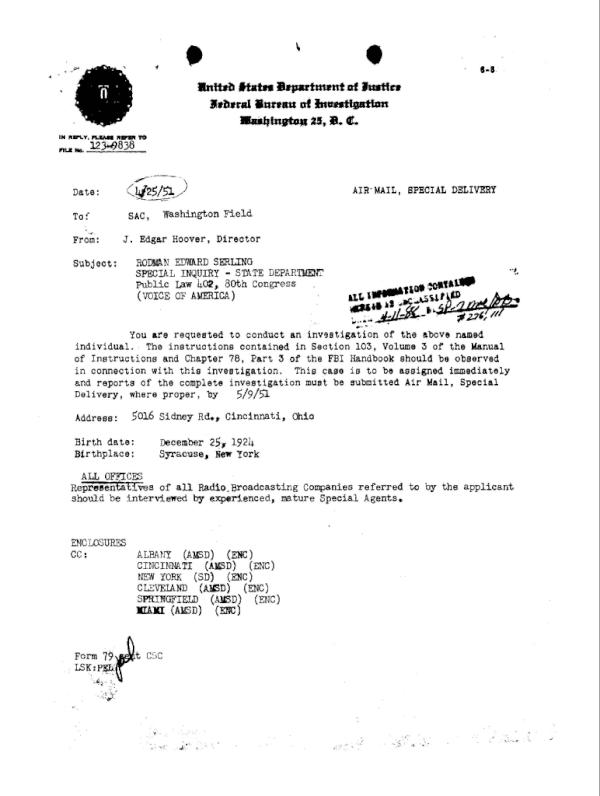

The first hint in knowing that the FBI investigated you were the people they sent to question your friends. These agents would not just talk to your friends or you employers; they would talk to almost everyone you had ever known well. Through the Freedom of Information Act I, acting on a hunch, requested the FBI files on Rod Serling the creator of the hit television series The Twilight Zone. What I found surprised me for two reasons. One was that Rod Serling, the writer of a television show that often criticized the nature of the Red Scare, was not investigated during the making of the show. The other reason I was surprised was that the file contained notes from a 45-page investigation. Serling was not being investigated for espionage or subversive activities; he had merely applied for a job as a writer on a government operated radio show called The Voice of America.

This is the first page of the Rod Serling file. Here we see J. Edgar Hoover sending out the first memorandum requesting the investigation.

To investigate this World War II veteran, the FBI dispatched agents to Albany, Cincinnati, New York, Cleveland, Springfield, and Miami, anywhere were Serling had spend any prolonged period of time in his entire life. Neighbors, employers, family members, co-workers, all were interviewed and asked to characterize his talent as a writer, his diligence, but especially his loyalty. Dozens upon dozens of people were interviewed and each FBI document concludes with the thought, “no information of a derogatory nature concerning loyalty which could be identified with the applicant was found.”[1]

In some instances the investigation became very specific and very personal. In a memorandum sent from Cincinnati, where Serling went to college, an FBI agent interviewed the director of a children’s summer camp where he had once worked. The director furnished the FBI with the only negative piece of information found in the entire investigation, “He said that applicant received an unsatisfactory rating during his employment period at Camp Treetops, Lake Placid, New York, due to his poor judgment in associations with his present wife at the camp when they were both single students and co-op employees during the summer of 1947.” And that, “they spend too much time together in front of the children of the camp.”[2] No dirty detail was left unrecorded.

The other ways in which a person knew they were being surveyed was, as Arthur Miller found out, the appearance of personal information and references to their FBI files while before the HUAC.[3] After the emergence and popular pulp stories of FBI informants, any new person, or old friend for that matter, could be an informant. The writer and Communist Party member Howard Fast had many overt run ins with the FBI. In his Memoir, Being Red, Fast remembers a dinner party that he threw. He writes, “On one occasion, on the day

before we gave a large fund-raising party, I received a drawing in the mail with the legend: “This bastard is FBI. He’s crashing your party. Throw him out.” It was a good drawing, and when the FBI man turned up, he was immediately recognized. He left quietly; if there was one thing you could give the FBI point for, it was politeness.”[4]

There are numerous memoirs written by those who were surveyed and all purvey the same sense of paranoia. As we see from the Serling records, the FBI’s investigations were often too deep and too thorough to go unnoticed.

[1] Washington Field Office-FBI, “Special Inquiry- Rodman Serling,” 5/21/1951.

[2] Cincinnati Field Office-FBI, “Special Inquiry- Rodman Serling.” 5/8/1951

[3] Christopher Bigsby, Arthur Miller. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009. Pp. 532.

[4] Howard Fast, Being Red: A Memoir. New York: M.E. Sharpe, 1990. Pp. 168.