“After Half a Century as America’s counterrevolutionary in chief, Hoover no longer commanded unquestioned authority…. The control of secret information had always been the primary source of Hoover’s power. He had lost it.” -Tim Weiner, Enemies, 288.

It was dark and late on the night of March 8, 1971 when for the first time in fifteen years eyes other than those of an FBI employee read the word “COINTELPRO.” The COINTELPRO, which stood for Counter Intelligence Program, was created in 1956 during the height of the second red scare as an aggressive campaign to redouble efforts to survey the American left. It was one of the darkest secrets the FBI had. Through the program, the FBI had clandestinely amassed thousands of files through illegal and

unconstitutional methods. Unless the FBI wanted to purposely leak information, the world would never know about the intelligence that had been gathered in the name of COINTELPRO. Even the Attorney Generals that Hoover was supposed to have been reporting to had no idea of the program’s existence. In the 1976 Church Committee hearing investigating the civil rights abuses of intelligence organizations, the committee found that, “To the extent that Attorneys General were ignorant of the Bureau’s activities, it was the consequence not only of the FBI Director’s independent political position, but also of the failure of the Attorneys General to establish procedures for finding out what the Bureau was doing and for permitting an atmosphere to evolve in which Bureau officials believed that they had no duty to report their activities to the justice department, and that they could conceal those activities with little risk of exposure.”[1] That is of course, until March of 1971.

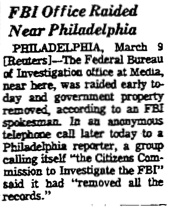

A few miles outside of Philadelphia, in a small town called Media, burglars working for the organization known as the Citizens’ Commission to Investigate the FBI broke into a small satellite FBI office and raided it, taking every classified document they could find.[2]It was the first time anyone had seen documents illustrating the depth of FBI surveillance. For the

next few months the organization continued to leak the information to certain members of the government, as well as members of the press who in turn, relayed the information to a stunned population. Tim Weiner writes, “It took weeks, in some cases months, before the reporters began to understand the documents. They were fragmentary records of undercover FBI operations to infiltrate twenty-two college campuses with informers, and the described the wiretapping of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panthers. It took a year before one reporter made a concerted effort to decode a word that appeared on the files: COINTELPRO. The word was unknown outside the FBI.”[3] The country was shocked. A few weeks later J. Edgar Hoover canceled the fifteen-year operation in hopes that no more secrets would leak, but it was too late. The days of an unquestioned FBI had come to an end. Hoover would stay on as director until his death, a year and two months after the break in. The second red scare had been over for nearly ten years but the systems put in place by that fear had stayed operational. Only after the revelations of 1971 could the public truly learn to what extent they had been watched for the past four decades.

Here is a photograph of J. Edgar Hoover's grave in Washington D.C. He died in 1972, a little over a year after the Media break-in.

[1] US Senate Select Committee on Intelligence Activities Within the United States. 1976 US Senate Report on Illegal Wiretaps and Domestic Spying by the FBI, CIA and NSA. St. Petersburg, Florida: Red and Black Publishers, 2007. Pp. 185.

[2] James Kirkpatrick Davis, Spying on Americans: The FBI’s Domestic Counterintelligence Program. Westport: Praeger, 1992. Pp. 1.

[3] Tim Weiner, Enemies: A History of the FBI. New York: Random House, 2012. Pp. 293.